When asked why she had sculpted such pronounced, sugar-coated labia on A Subtlety, the mammy-sphinx recently on view at the Domino Sugar Factory in Brooklyn, Kara Walker answered, “[It’s about] ownership of the voluptuousness of an ass”; “a 10-foot vagina…is not something that happens in art often enough”; and “[It was] a fuck-you, I’m gonna do that because this is what I have…there are enough phallic symbols in the world…” Visitors to Daughter of Bad Girls—a new exhibition at Klaus von Nichtssagend Gallery that positions seven contemporary artists as heirs to the fierce femmes that appeared in Marcia Tucker’s 1994 exhibition, Bad Girls, at the New Museum and Bad Girls West, its sister exhibition at the Hammer Museum in L.A. (then UCLA’s Wight Art Gallery)—are, a little disappointingly, greeted not by the vagina but by two phallic lacquer-and-ceramic sculptures of genetically manipulated Roma tomatoes by Jessica Rath. As glossy and fecund-looking as they are, these two sleek red forms give the male part undue emphasis in the small gallery space. Not all of the works in Daughter of Bad Girls go so far astray, but on the whole the exhibition cannot help but pale in comparison to the potent era of third-wave feminist art that it invokes.

When asked why she had sculpted such pronounced, sugar-coated labia on A Subtlety, the mammy-sphinx recently on view at the Domino Sugar Factory in Brooklyn, Kara Walker answered, “[It’s about] ownership of the voluptuousness of an ass”; “a 10-foot vagina…is not something that happens in art often enough”; and “[It was] a fuck-you, I’m gonna do that because this is what I have…there are enough phallic symbols in the world…” Visitors to Daughter of Bad Girls—a new exhibition at Klaus von Nichtssagend Gallery that positions seven contemporary artists as heirs to the fierce femmes that appeared in Marcia Tucker’s 1994 exhibition, Bad Girls, at the New Museum and Bad Girls West, its sister exhibition at the Hammer Museum in L.A. (then UCLA’s Wight Art Gallery)—are, a little disappointingly, greeted not by the vagina but by two phallic lacquer-and-ceramic sculptures of genetically manipulated Roma tomatoes by Jessica Rath. As glossy and fecund-looking as they are, these two sleek red forms give the male part undue emphasis in the small gallery space. Not all of the works in Daughter of Bad Girls go so far astray, but on the whole the exhibition cannot help but pale in comparison to the potent era of third-wave feminist art that it invokes.

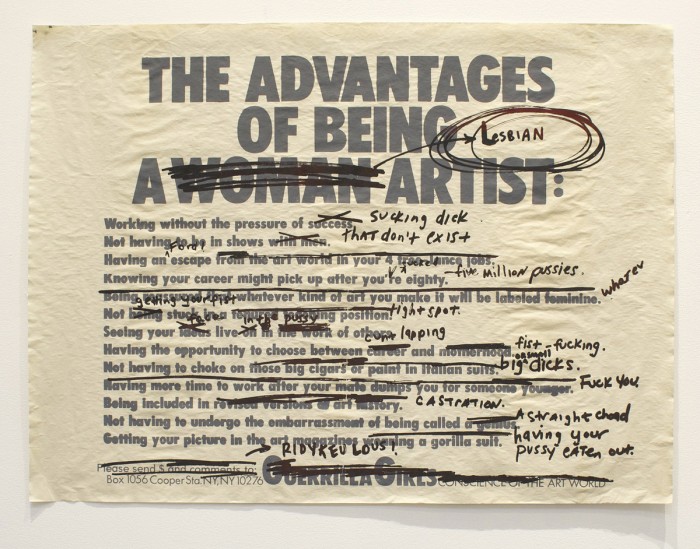

Turning polite, palatable “feminine” behavior on its head with rebellious, even anarchist abandon, Daughter of Bad Girls aims to pick up where predecessors like Riot Grrrls and Kathe Burkhart left off. Xaviera Simmons, in a large-scale photographic self-portrait, presents herself sprawled horizontally on a striped picnic rug, masturbating in broad daylight. The noisy collaborative duo Ridykeulous, made up of A.L. Steiner and Nicole Eisenman, defaces a printed copy of the Guerrilla Girls’ famous poster The Advantages of Being a Woman Artist (1989), which laid out in stark terms the appalling state of female representation in the visual arts. Eighteen years on, Ridykeulous’s brazen revision of this key text, The Advantages of Being a Lesbian Woman Artist (2007), suggests feminist offspring unafraid of cannibalizing their revolutionary forebears. According to Ridykeulous’ vandalizing scribbles, “Working without the pressure of success” becomes “Working without the pressure of sucking dick.”

Sucking dick is exactly what Ann Hirsch proposes in her video work Here For You (Or My Brief Love Affair with Frank Maresca), a delicious send-up of VH1’s The Bachelor, in which preened, perma-tan girls vie for the attentions of a calendar-boy hunk. Hirsch herself joins a cohort of contestants, countering their banal platitudes and on-cue peals of vapid laughter with antics that include twerking in a bikini for her audition tape and regaling the bachelor with an obscene song in which she tells him everything she wants to do to him.

Other works in the show are quieter but no less transgressive. Alice Mackler’s wan ceramic figure, a misshapen, depraved-looking blob (nonetheless recognizable as female), is absorbingly touching and human, as is her sketchy, infantile acrylic-, gouache-, and ink-on-paper drawing of two distorted figures composed of swollen sexual organs and orifices. Sue Williams’ maelstroms of cartoonish, sexualized imagery come to mind. Mackler’s two works present the female as hybrid, ungendered, and manifesting a powerful presence of mind. It’s easy to see why the artist, an octogenarian and lifetime New Yorker, is currently receiving a wave of belated acclaim. Vaginal Davis, the intersex, gender-queer artist whose name pays homage to the former Black Panther and West Coast activist Angela Davis, presents a series of childishly drawn female heads painted onto letterhead paper and displayed as a grid. They recall the reverent, innocent fascination of young girls with older, glamorous women.

The strength of Daughter of Bad Girls lies in its nuanced and eclectic grouping of female artists, representing a range of generations, races, and sexual orientations, which offers a snapshot of what female artists—not all expressly feminist, but all with a feminist bent—are producing today. Individually, several of the works on view here are hilarious, incisive, and absorbing, but as a collective fuck-you to the male-dominated establishment, the exhibition cannot stack up to its namesake. This is partly a problem of scale. One can hardly compare an exhibition of nine artists in a tiny Lower East Side space against a sprawling museum show that featured forty-five artists, many of them now iconic—a “raucous caucus,” as Roberta Smith dubbed the cohort in her 1994 New York Times review. But beyond that, the “Bad Girls” trope seems worn thin. It lacks the punch it once had, especially in today’s era of Vice bloggers like Slutever. Female artists still have a mountain to climb when it comes to demanding equal representation in the visual arts and overcoming biases in society at large, but today’s conditions call for something more than a repackaging of ‘90s-era feminist art. What would a fourth wave of feminist artists look like?