Tamara Gonzales

Kemar Keanu Wynter

We recommend the latest version of Safari, Firefox, Chrome, or Microsoft Edge.

Tamara Gonzales

Kemar Keanu Wynter

Klaus von Nichtssagend Gallery is presenting a two person exhibition at the Independent of works by Tamara Gonzales and Kemar Keanu Wynter. Both Gonzales and Wynter were invited to create work at artist residencies in 2022, where they developed the new and significant bodies of paintings and drawings on view at the fair.

Klaus von Nichtssagend Gallery is presenting a two person exhibition at the Independent of works by Tamara Gonzales and Kemar Keanu Wynter. Both Gonzales and Wynter were invited to create work at artist residencies in 2022, where they developed the new and significant bodies of paintings and drawings on view at the fair.

Tamara Gonzales (born 1959 Madeira, CA) was at the MeMeraki Artist Residency in Limassol, Cyprus last summer. While there, she immersed herself in local cultural traditions that influenced a series of works on paper she created in the studio, as well as a large scale painted tapestry. Her new work captures the colors of Cyprus, incorporating Mediterranean inspired cerulean blues, while maintaining her singular stylistic figurative forms and energetic mark making.

Kemar Keanu Wynter (born 1995, Brooklyn, NY) makes works on paper using luscious oil pastels and vibrant watercolors, titling each piece after culinary dishes he has shared with family and friends. At recent residencies ARoS Kunstmuseum in Aarhus, Denmark, Art Quarter Budapest in Budafok, Hungary and at Anderson Ranch in Snowmass, Colorado, Wynter further developed a series of color pencil and watercolor drawings, and works on grommeted collaged paper. The latter works are hexagonally shaped, looking to traditions of heraldry and shields as substrates for his dynamic and colorful mark making done in thick, buttery oil pastels.

The following is an exchange originally published on the Independent’s OVR between Tamara Gonzales, Kemar Keanu Wynter and Ingrid Bromberg Kennedy in anticipation of their 2023 presentation at the fair.

Ingrid Bromberg Kennedy: You both live in Brooklyn but have traveled to residencies to make work. Is there something about being away from home that inspires your work?

Tamara Gonzeles: In this case yes. This past July I was at Memeraki Artist residency in Limassol Cyprus. The light was so bright. I was close to the water and it was that deep blue. And there were bright orange round buoys floating on thy horizon and of course the sun. It was visually seared into my brain and that really influenced the pallet of the summer.

IBK: You have been on a number of residencies recently, Kemar — what does a shift in location do for your working process? Does it create a color palette shift like it does for Tamara? Or is it useful to you in other ways: a cuisine shift? Or a space away from the busy city to focus on ideas already brewing?

Kemar Keanu Wynter: Residencies are invaluable in my practice simply for the shift in volume. The activity and noise of the city is in the air and I find that makes it really difficult for me to focus in on work during the daytime; when I’m home I find that my best working hours working are from 8pm – 2am, there’s something wonderful about that feeling of the city slowing down, it’s like the city has the airplane mode button switched on. When I get out to a residency, say it’s Ox-bow or The Macedonia Institute, I get those late night hours all the time. I become a different person in some ways and will wake up at the crack of dawn and just cook in the studio for the whole day. On residencies, I certainly get to embody a different part of myself and I feel that audible, spatial, personal shift is vital to some of the major breakthroughs that I’ve had in my practice.

Color is something that I’ve become more aware of shifting, as of late. I started my residency at Anderson Ranch at such an interesting time of year. Arriving in early October I was met with the shimmering golds of the Aspens and their mottled barks but by the end of the residency, my view on a daily basis was vast expanses of white snow and the wavering browns of cabin wood grains. I got into the habit of going on hikes with a fellow artist, and on the path, I kept honing in on this one sliver of rock in the face of the mountains in the nearest range. The rock around it was the usual taupe, ochre you could generally expect but this one section was just a channel of pink. In the afternoons when the sun hit that side of the valley, that stone glowed hot like an angry wound. Those groupings of color are etched into my memory. I think during my time as of late, I’ve definitely tried to tune into more of the way colors jostle against one another and take up space, attention when in proximity to one another.

Wynter applies oil pastel in lines that swirl and smear across the paper, so that his compositions are bound by the density of their own centers rather than any external structure or gravity. An entire language of marks seems to unfurl and come back into focus.

Louis Block

Brooklyn Rail

IBK: You both are influenced by the routine of daily life: for Kemar it can be cooking and eating with family and friends, for Tamara it is spiritual practice. How do these experiences show up in your work?

T: Yes my spiritual inquiries are in the work, and so are all my activities, relationships, personal struggles, world struggles, weather. And very much the space I’m working in, with regards to scale and material. As for trying to directly put any of that content in the work I would say It’s more that I am engaged in the activities of the materials, pencils, wet paint, spray paint, be it all over pattern or more distinct imagery and the content emerges or reveals itself to me. Anyway it’s all more clear in the rear view mirror so to speak. Often in a studio visit or a viewer’s remark will fill in the missing pieces.

IBK: Kemar, you title your works after dishes or meals you have eaten, but the work is very abstract. How do you come up with the titles? Do meals inspire a direction for individual pieces?

K: Titles always come first. Early on I knew abstraction would be dead for me if I didn’t have something to serve as its engine, and food has been integral for breathing life into each painting. I come from a family that cooks heavily; my Auntie Del, matriarch of the Wynters, would have the entire family over for dinners every Friday without fail as a child and it was in those moments that I learned to cook. Right now I’m working primarily with dishes from my family, but whether they be from home or the neighborhood or out on the road, every meal has a story. Each of those stories, the vignettes that often accompany my work, serve as the foundation from which my decisions about each painting are built.

IBK: Does the color in your work come intuitively as well?

K: Not purely. Writing about each dish helps me to hone back into singular moments with the dish. In that ritual I recall the flavor palette, the ambiance, the conversations around the meal and from that I can pull an initial five or six colors which serve as the grounds for each painting. From there the process becomes more intuitive, where I’m building a palette that toes a line between encompassing my relationship with the meal and serves to make an excellent painting. There is a moment where each surface starts chatting with me and we give and take to reach the end painting.

IBK: Tamara, how do you think about color in your work?

T: It plays a huge part and it usually unfolds intuitively. But Sometimes there’s a studio mission to just use up the paint I have left. A self thrown curve ball so to speak.

IBK: How do you each think about mark-making?

T: It feels pretty emotional. Or like taking a mental self temperature. And also very much a muscle in that continued drawing or doodling keeps ideas flowing and often the drawings seem ahead of the paintings.

K: I think that to talk about ‘mark’, I need to speak on ‘medium’ for a moment. I work in oil pastel, primarily, and that choice felt incredibly natural due to my time in the kitchen. The way that pastel is responsive to heat and coated my fingers with grease and pigment felt akin to when I would flip escovitch fish or cornmeal dumplings shallow frying with my fingers and how they’d be covered in oil, often time-tinged with sazon or browning or some other thing from the pantry. The materials I work with, I do because they’re a pleasure to use; having that joy with what I use means there’s one less variable to contend with in the studio.

I picked up oil pastels over six years ago and haven’t put them down since. I can’t really say there’s a way I got to making marks the way I do, I just think that I’ve just found what feels right to the body and makes sense for the material in this time.

[Gonzales] has an indiscriminate appetite for cross-cultural pollination and distills the dissonance of contemporary life into these objects that can seem as jarring as they are soothing.

Hrag Vartanian

Hyperallergic

K: The first work of yours I ever saw, Tamara was this beautiful denim tapestry with incredibly masterful needlework done by craftswomen you have worked with repeatedly over the years. Could you tell me more about your relationship and how collaboration has informed and modified your practice over time?

T: I was in Pucallpa Peru drinking ayahuasca with the Shipibo. Once a year I would visit for a couple of weeks. There is a lot of beautiful traditional embroidery being done on many upcycled items, t-shirts, yoga pants, hoodies and dresses. People were getting dresses and blouses embroidered and I got a download. The next time I visited I brought some denim pieces of fabric that I had made a simple chalk outline on. It was a loopy line framing device and a boxy figure, both which I use a lot. One of the Shipibo and owners of the center I was visiting, Beatrice and I got into a conversation about the drawings I had in my sketchbook. She could see the visions in them, so I left them with Beatrice and just trusted the process. I was bowled over by the results. I think there are about 10 that got finished. We were hoping to have more of an exchange going but the whole process was interrupted with Covid. In many ways the relationship and collaboration is just being in a place, drinking aya, and a serendipitous meeting with a craft person. With the Shipibo style of embroidery the actual imagery that was used back and forth, mine and the more traditional, ended up coming more directly into the paintings.

T: Do you ever find the title you started with needs to be changed? Like maybe the painting was making a new recipe and you are in some new territory?

K: Oh definitely, title changes are those happy accidents that I look forward to in the studio. When I get to work, I usually have a list of dishes that I’d like to tackle. As I’m dotting around between pieces I can oftentimes find that my brain might return to a particular dish as I’m actively painting another. That bleed-over on more than one occasion has had me take a step back after some hours and realize that the surface I’m actually handling in the moment is a more suitable depiction of the intruding meal than the intended surface – and by extension that new surface has a good bit of conflict for me to wrestle with to make something exciting for the other painting.

Alternately, certain titles need more specificity and become longer. I had a Curry Chicken in the studio recently, one of my mother’s specialties and I realized as I was writing that what were important for me than the stewed chicken itself were the butter beans and Irish potatoes; they were definitely intended to be the supporting elements of the dish but for me they always stole the show. Both ingredients were sponges for the curry and became these tender morsels that simply exploded with flavor. I always snuck the extra potatoes from the leftovers because they were simply that good. I made sure that the title was Curry Chicken, Butter Beans and Irishes because the dish, and painting are tragically incomplete without the whole trio.

Kemar, when you described your oil pastels coating your fingers bringing up memories of cooking and the way oil functioned in the kitchen I got such a flash of recognition. My mother owned a bakery and I was a cake decorator. The similarities of paint and frosting or maybe even how I work with embellishment probably comes out of that time. Your description of the pleasure of your materials, the meals, the conversions, and everything that comes to mind through a dish that then becomes the paintings is very moving.

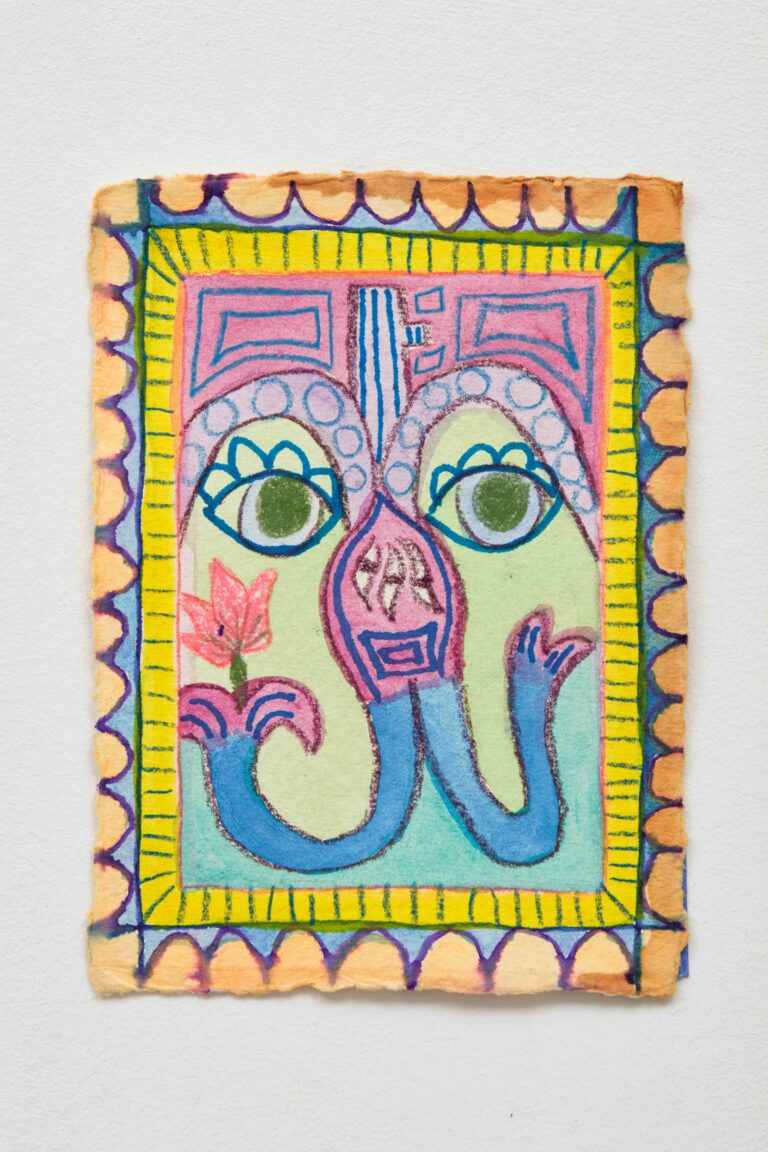

Tamara Gonzales

Limassol drawings, 2022

colored pencil, ink, and watercolor on watercolor paper

6 ⅛ × 4 ½ inches (15.56 × 11.43 cm)

TG1348

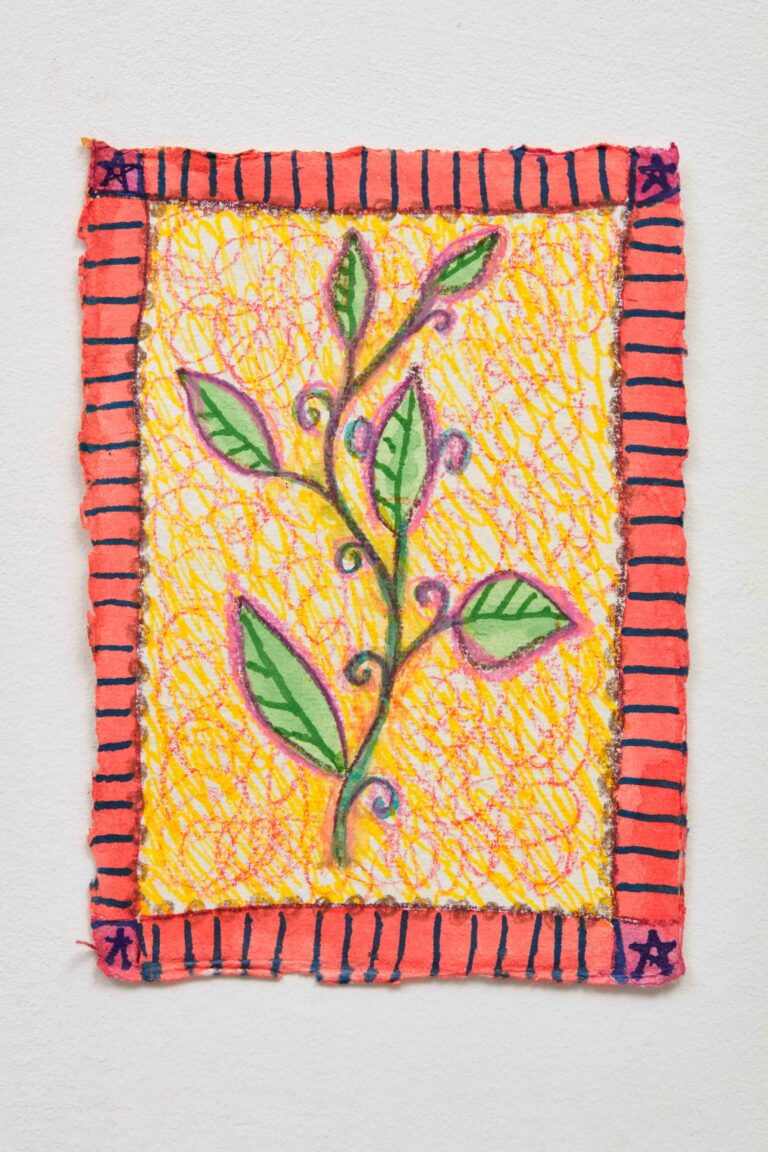

Tamara Gonzales

Limassol drawings, 2022

colored pencil, ink, and watercolor on watercolor paper

6 ⅛ × 4 ½ inches (15.56 × 11.43 cm)

TG1342

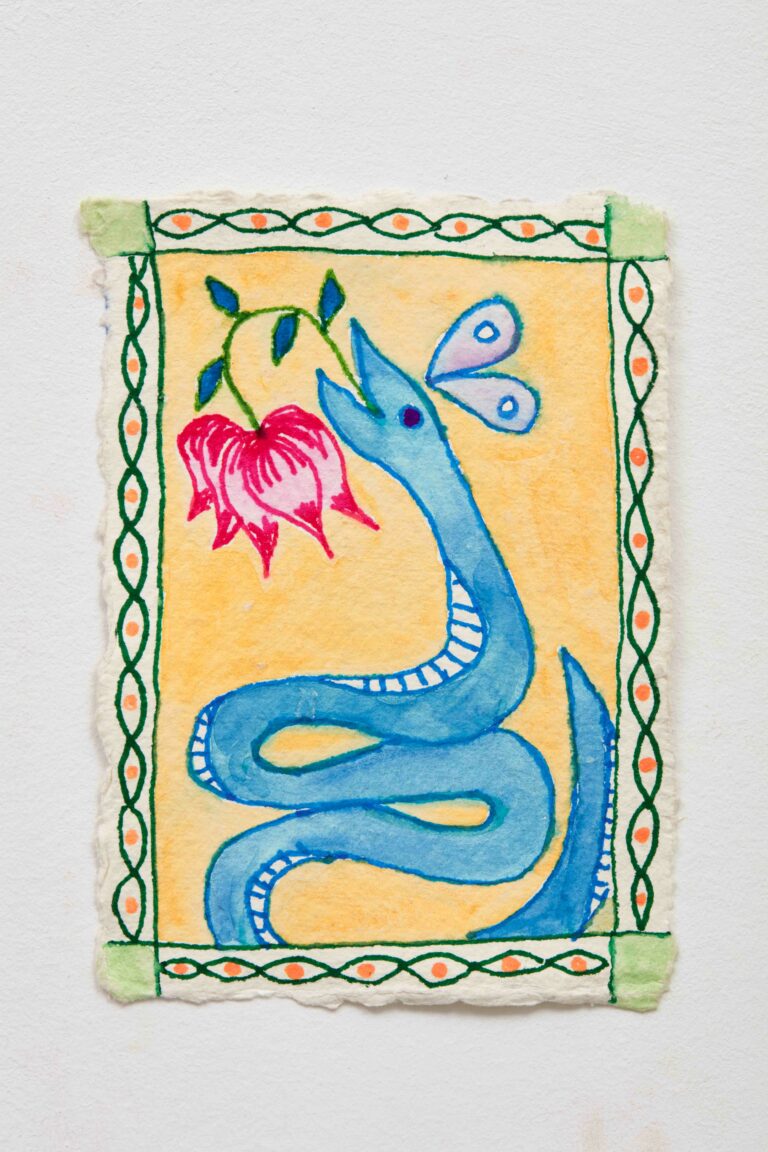

Tamara Gonzales

Limassol drawings, 2022

colored pencil, ink, and watercolor on watercolor paper

6 ⅛ × 4 ½ inches (15.56 × 11.43 cm)

TG1337

Tamara Gonzales

Limassol drawings, 2022

colored pencil, ink, and watercolor on watercolor paper

6 ⅛ × 4 ½ inches (15.56 × 11.43 cm)

TG1336

Tamara Gonzales

Limassol drawings, 2022

colored pencil, ink, and watercolor on watercolor paper

6 ⅛ × 4 ½ inches (15.56 × 11.43 cm)

TG1334

Tamara Gonzales

Limassol drawings, 2022

colored pencil, ink, and watercolor on watercolor paper

6 ⅛ × 4 ½ inches (15.56 × 11.43 cm)

TG1333

Tamara Gonzales

Limassol drawings, 2022

colored pencil, ink, and watercolor on watercolor paper

6 ⅛ × 4 ½ inches (15.56 × 11.43 cm)

TG1331

Tamara Gonzales

Limassol drawings, 2022

colored pencil, ink, and watercolor on watercolor paper

6 ⅛ × 4 ½ inches (15.56 × 11.43 cm)

TG1327

Tamara Gonzales

Limassol drawings, 2022

colored pencil, ink, and watercolor on watercolor paper

6 ⅛ × 4 ½ inches (15.56 × 11.43 cm)

TG1323