The I Has to Travel

We recommend the latest version of Safari, Firefox, Chrome, or Microsoft Edge.

We have all heard some iteration of the phrase “history repeats itself.” This famous sentiment can be attributed to Karl Marx whose statement in full reads: “History repeats itself, first as tragedy, second as farce.” Of course, history cannot literally recur, but comparable situations do arise and our responses to them can mirror past experiences. Not even a century ago, a number of issues that are currently plaguing the United States had similarly beset the Weimar Republic, Germany’s first attempt at democratic governance, ultimately causing its demise and giving rise to the Nazi’s particular brand of fascism. The requisite reappraisal of the human body after mass death; the right-wing backlash to social progress (specifically female, gay, and trans visibility) and the impotence of the left to effectively curtail it; a general feeling of alienation despite having access to technology that can connect people more than ever before; and a culture of mass entertainment spurred by recently developed media are just a few of the striking if not exact one-to-one parallels that can be made between our time and the Weimar period. But instead of the effective rantings of a war veteran turned self-appointed political messiah, we have a man whose ridiculous social media ramblings suggest he possesses the self-control of a toddler: tragedy becomes farce. As an art historian studying this epoch, I couldn’t help but wonder: Are we doomed to replicate the past or can we take stock of our history and begin anew?

“Self-portraits are not innocent reflections of what artists see when they look in the mirror. They are a part of the language painters use to make a point, from the simple ‘this is what I look like’ to the more complicated ‘ this is what I believe in.” – Frances Borzello, art historian.

Given the similarities of these periods, it should not be a surprise that artists from both would employ self-portraiture to comment on the societies in which they have found themselves. As a subgenre of portraiture, self-portraiture is particularly suitable for this task as it renders the artist’s beliefs and aspirations without imposing them on someone else all the while professing self-assurance, even if it is just a facade. Furthermore, the self-portrait enables the artist to situate themselves squarely within their specific context (temporal, physical, emotional) in order to critique it. A self-portrait oscillates between existing within the sphere of the private and the public. These artworks reveal how the artist views themselves, both physically and psychologically, and places them in their distinct culture, epoch, society, or community.

Artists find themselves in a unique social position as public figures who can mine their private experiences in the world to use as subject matter for an artwork that will implicitly or explicitly remark on contemporary concerns, general or otherwise. This ability exclusive to artists is a result of an inherent tension within the role of “Artist:” those who identify with this role are at once marginalized and centralized within culture by this self-assertion. These seemingly opposing states are best perceived in self-portraiture for, to quote the art historian Irit Rogoff, the representation of “artistic marginality provides a critical position from which to view the activity at the centre and the artist’s relation to it.” (Rogoff 127) So although artists cannot enact political change directly, they have the power to critically examine their zeitgeist and ultimately persuade public opinion. This is why fascists and totalitarian governments attempt to control the production of art to fit their own propagandistic means.

For the artists associated with the Neue Sachlichkeit (insufficiently translated as the New Objectivity), the dominant art movement of the Weimar Republic, self-portraiture was a way to present themselves as cultural leaders who could guide the fledgling republic through its rocky inception. As competing political parties vied for dominance, artists made use of their position within the culture to be an additional view, one that alleged to be—at least in the early years of the Republic—of and for the German working class. Nearly all of the major Neue Sachlichkeit artists painted at least one self-portrait. Male artists adopted the genre to depict themselves as being modern individuals who were best suited to contribute to society. Much of the trauma of the war was worked through in these canvases: in order to appear virile and hyper-masculine in the face of a humiliating defeat, men degraded women who were at best depicted as vacuous models-for-hire and at worst mutilated corpses (known as Lustmord paintings). As a response, women artists, having just won suffrage and admittance into art academies nationwide, produced self-portraits that examined the stereotypes society tried to force upon them, specifically that of the neue Frau (new woman). Their canvas tackled how they negotiated traditionally feminine roles while simultaneously demanding to be treated equally to their masculine peers. Both male and female artists referenced art-historical precedents within their self-portraits to further lay claim to the role of “artist” as a means of self-legitimization.

Little has changed with contemporary self-portraits except that today, artists have the additional task of performing this role on multiple levels with the emergence and proliferation of social media. Artists now must manufacture two identities, the virtual and the real, with the former requiring the opposing qualities of “authenticity” and “perfection.” The social media identity is idealized, a “self” constructed out of carefully selected images that purports you “woke up like this #nofilter” despite the numerous discarded selfies that will never see the light of day. Social media’s capacity for fostering narcissism is one of the more insidious effects it has on users, but it is not all bad. The utopian aspect of the digital realm is its ability to empower people to present themselves as they want to be seen, transcending the physical and economic boundaries that oppresses minorities. Most of this contemporary identity building is achieved through the posting of selfies.

Selfies should not be equated with self-portraits. As Anirban Baishya notes on the difference between the two: “The connection of the hand to the cell phone at the moment of recording makes the selfie a sort of externalized inward look, and the point of view of the selfie is not necessarily the external gaze of the painter’s eye as he steps out of his body to see and render his own form, but that of the hand that has been extended the power of sight.” (Baishya 1688) With the selfie giving us the power to look within from an outside source, they are therefore more authentic, in the sense that it is a result of the selfie-taker’s interest in immediately capturing their interiority at that particular point in time. Because they only capture a fraction of the 24 hours in our day, we choose our “best” moment to post for posterity. Even if consciously we know that the life one displays on their social media profile is heavily fabricated and the selfies we are edited to some extent, we intuitively compare our physical lives to what we see because we believe in photography’s truth-telling abilities, regardless that it is no less deceptive than other image-producing methods (painting, sculpture, etc.). At the very least, perhaps, the continued proliferation of social media will bring attention to the fact that the self is not fixed but is in a state of continual modification and evolution.

“I loathe narcissism, but I approve of vanity.” ― Diana Vreeland, fashion editor and style icon

Since the 1980s, it has been accepted in sociology that the self is fragmented and is constructed primarily out of social interactions, with authors ranging from Foucault to Butler providing commentary on the tension between the real and the invented. In Stigma (1963) Erving Goffman argues that the self is made up of three identities: the social identity, the personal identity, and the ego identity. The social identity can be understood as the self that is working to fit within previously established social categories to enable the individual to respond appropriately in given situations. The personal identity is made up of one’s individual history and the public identifiers that make us unique entities (SSN, government names, etc.). The ego identity is the most intimate as it is the part of the self that the individual creates to reflect their core being. The first two identities are external in that both are imposed definitions of a person. It is only the ego identity that individuals have control over.

Considering these three identities in relation to social media reveals a slight shift in the power dynamic inherent in identity within society. On social platforms, the user has the freedom to choose the creators/groups they follow and interact with, their own identification monikers, and how they manufacture their online presence. The self one presents online is no more and no less authentic than the self you would find offline, they just might look different. These two identities are created by the same individual. Furthermore, there cannot be a clear distinction between the online and offline self anymore, even beyond presentation: Nathan Jurgenson highlights that even when we are not actively on our technological devices, when we are unplugged from the digital, part of our consciousness is still logged on, wondering what we should post next or surveying our surroundings for the perfect photo to share. Yet, it is difficult for most to admit that their identity is at least in part constructed and performed, something that criticism of social media highlights. We have been raised to be “true to ourselves” without acknowledging that what was true to us in the past might no longer be a personal fact in the present. As hard as it might be to accept, there can never be an essential truth to one’s self. If there were, humanity would have stagnated long ago.

In the realm of social media, we expect an honest portrayal of the people we see even though we are keenly aware of the fabricated nature of the platforms since we are actively participating in the same forgery machine. In the realm of art, however, we accept that a portrait (of the self or another person) is made from a careful consideration of what the sitter and the maker want to say. We expect and welcome an amount of artifice because we recognize that it is a product of artistic expression. Often, the artist’s work is in direct conversation with changes in society whether it be, for example, new technology (Impressionism) or political upheaval (Neue Sachlichkeit). Thus, it should not be seen as brazen to suggest that how we conceive of what it is to be an artist and how we view their presentation is in the process of changing because how we see and understand people through the images they choose to present to the world has fundamentally changed.

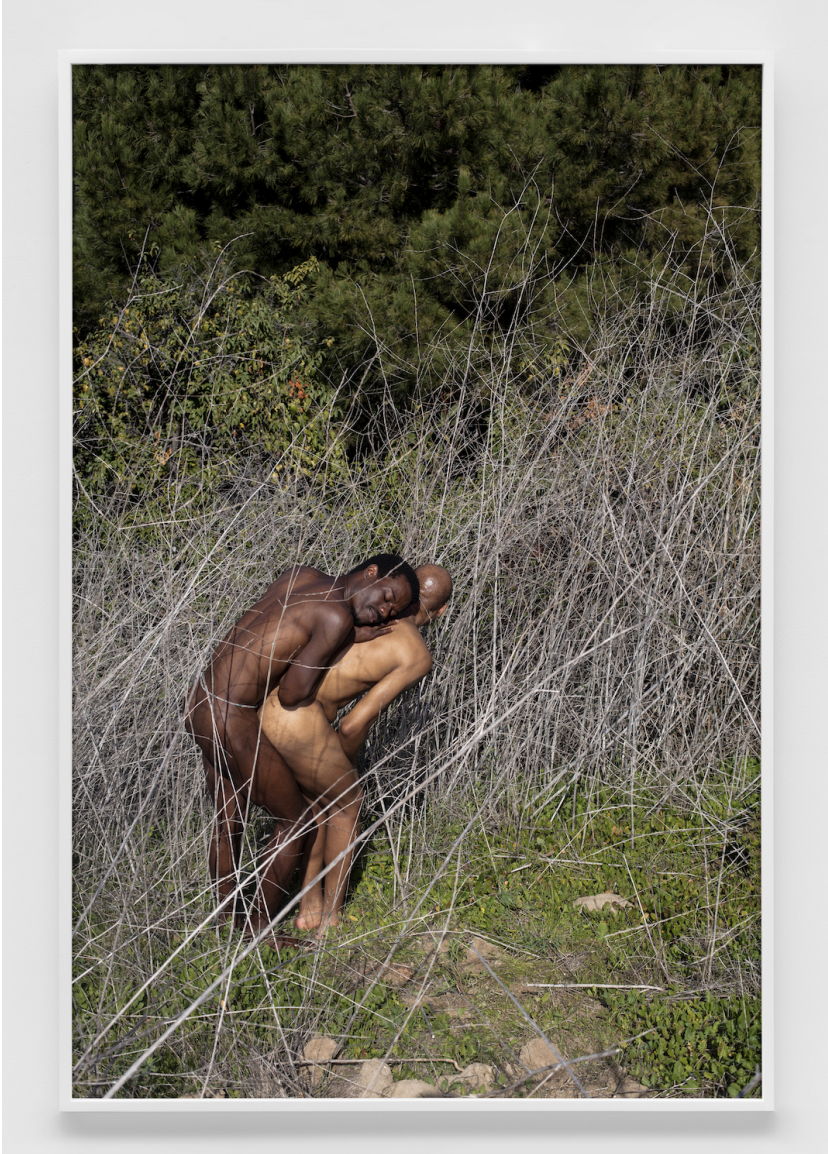

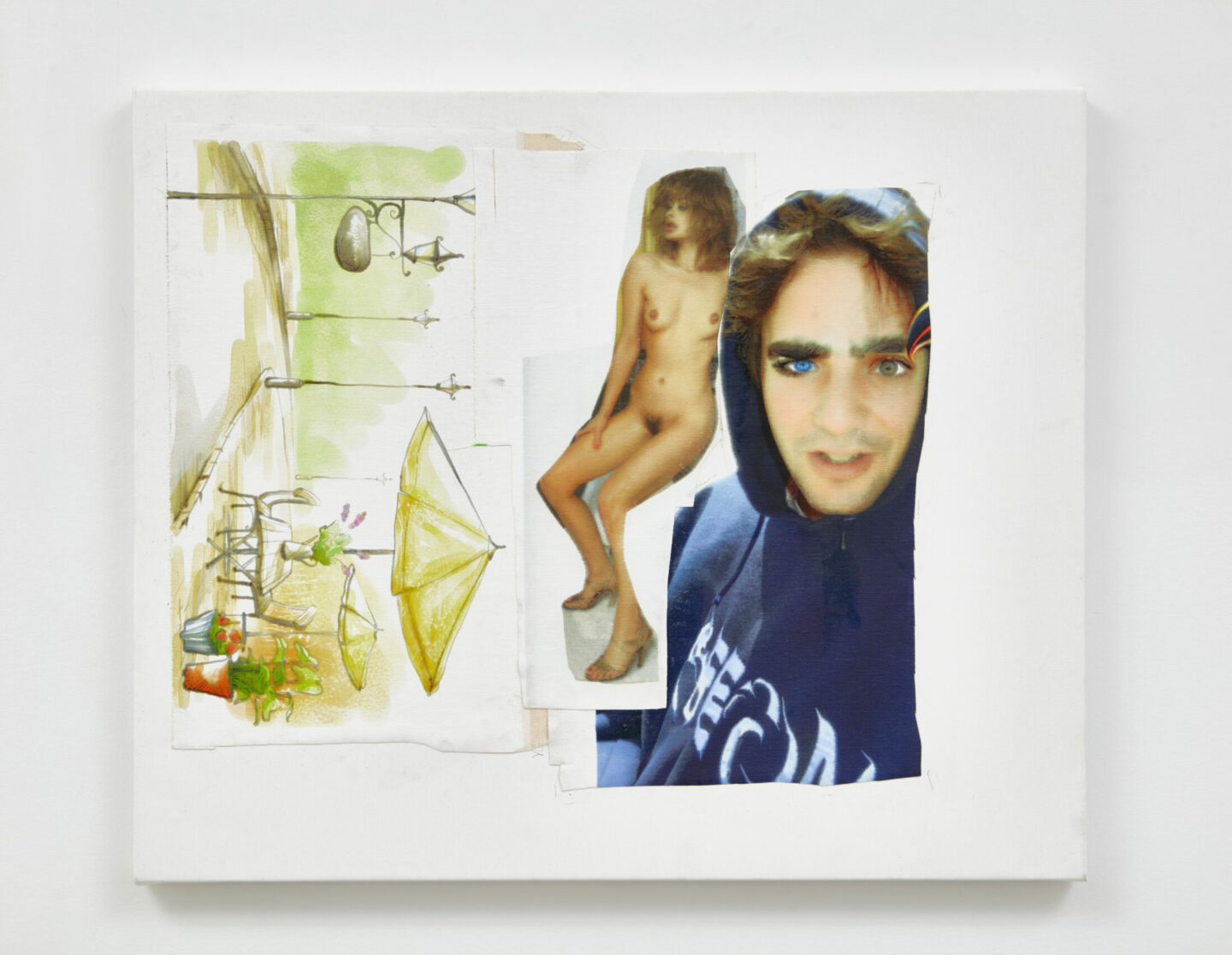

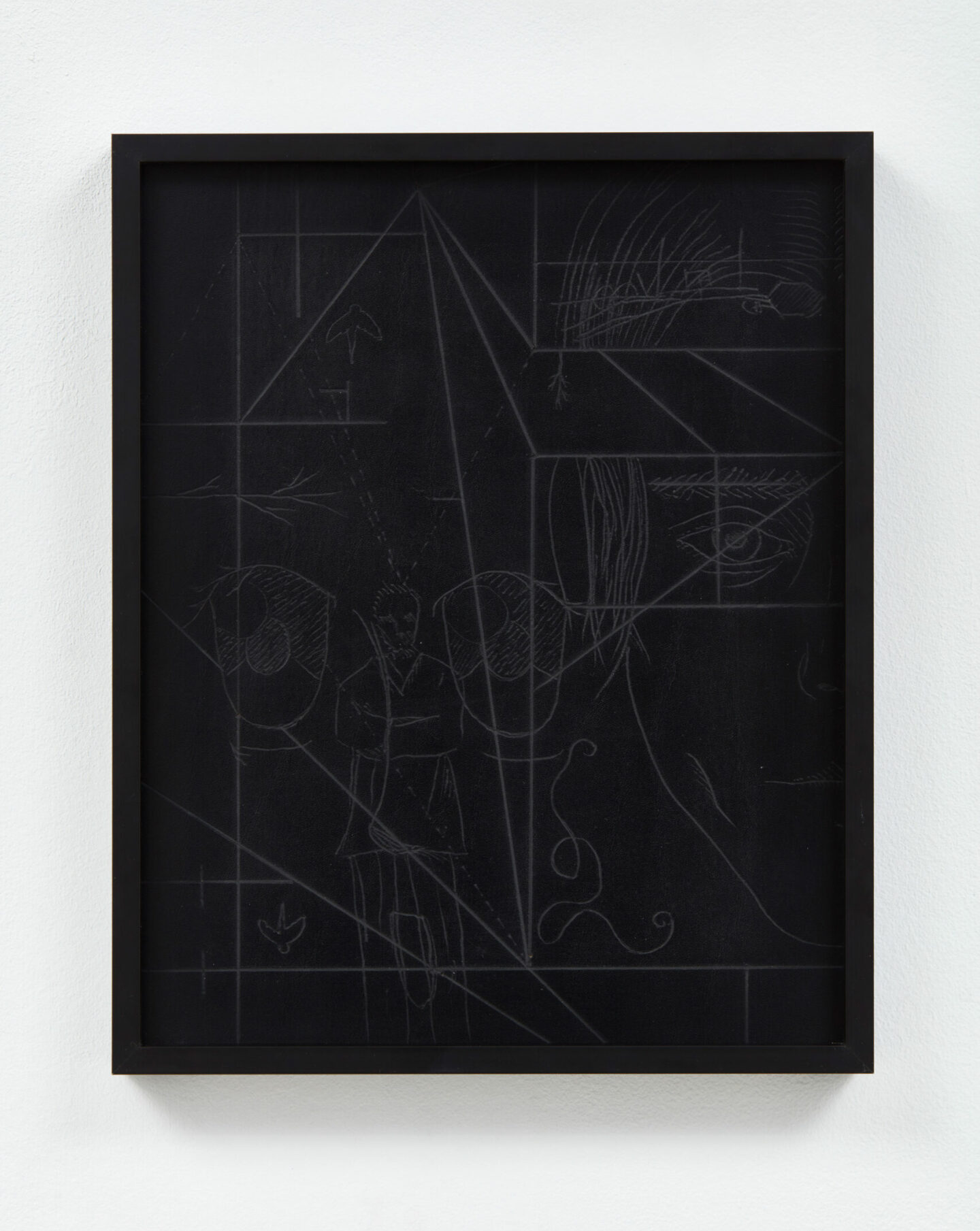

The eight artists who are represented in The I Has to Travel are all implicitly or explicitly exploring this development. Their artworks, although of varying mediums and techniques, possess a noticeable tactility, placing them firmly within the real. Additionally, each artist examines the constructed aspect of the self, by referencing artistic influences, personal history and relationships, community (either macro and micro), now-ubiquitous image-editing techniques, and even the creative process itself. As a result, the works on display demonstrate how contemporary artists are conscious of the new ways in which their identities are manufactured, both on- and offline and how they are responding to this metamorphosis of the self through their unique practices.

Inquire

Installation shots of The I Has to Travel, on view at Klaus von Nichtssagend Gallery through August 11, 2023.

For more information on the show, click here.

Lotte Laserstein, At the Mirror, c. 1930.

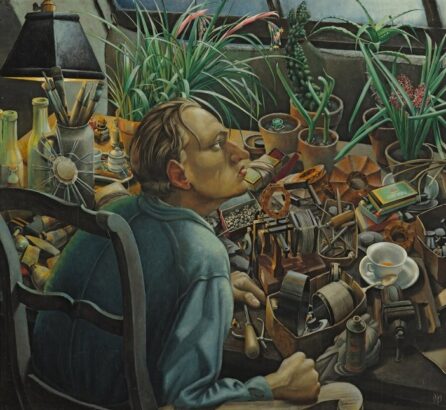

Wilhelm Heise, Withering Spring: Self-Portrait as a Radio Tinkerer, 1926. Oil on wood, 33.07 x 35.43 in., Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus und Kunstbau München.

Georg Scholz, Self-Portrait in Front of an Advertising Column, 1926. Oil on canvas, Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe.

Kate Diehn-Bitt, Self-Portrait in Black Underwear, 1932. Kunsthalle Rostock.

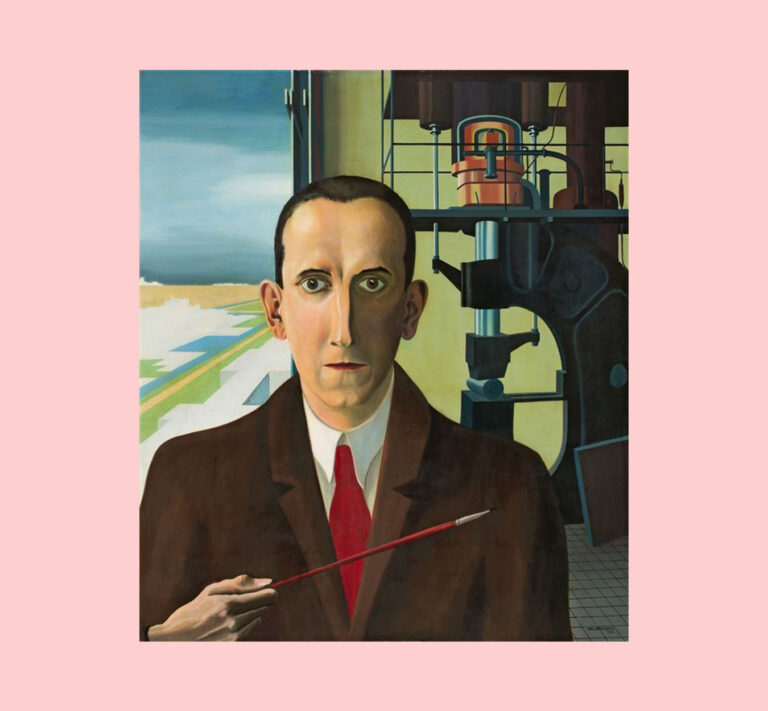

Carl Grossberg, Self-Portrait, 1928. Oil on wood.

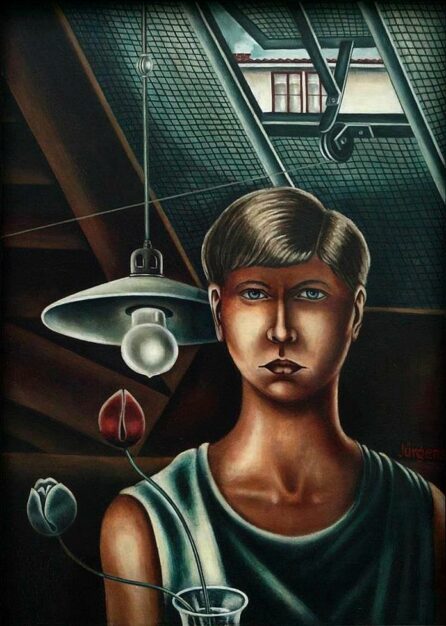

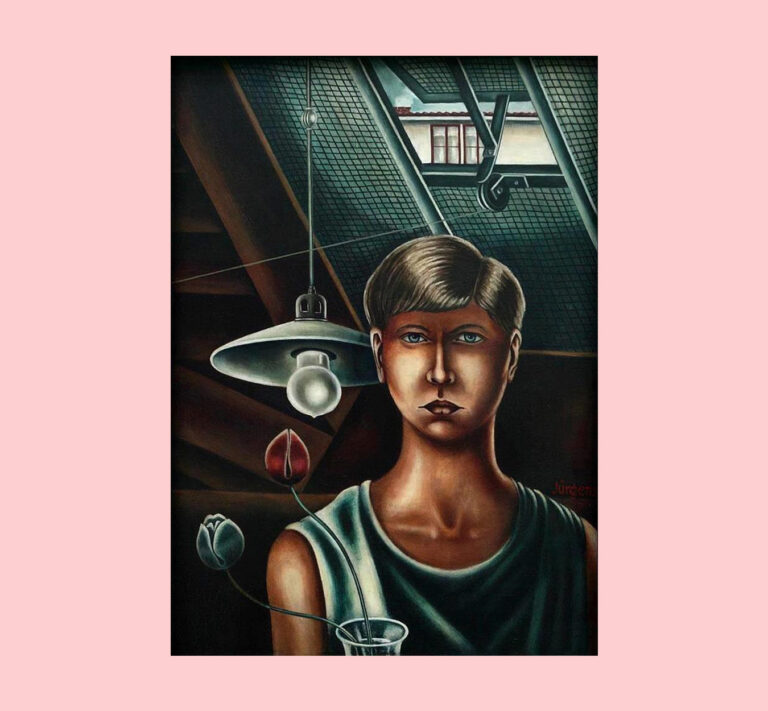

Grethe Jürgens, Self-Portrait, 1928. Oil on wood, 28.74 x 20.87 in., private collection.

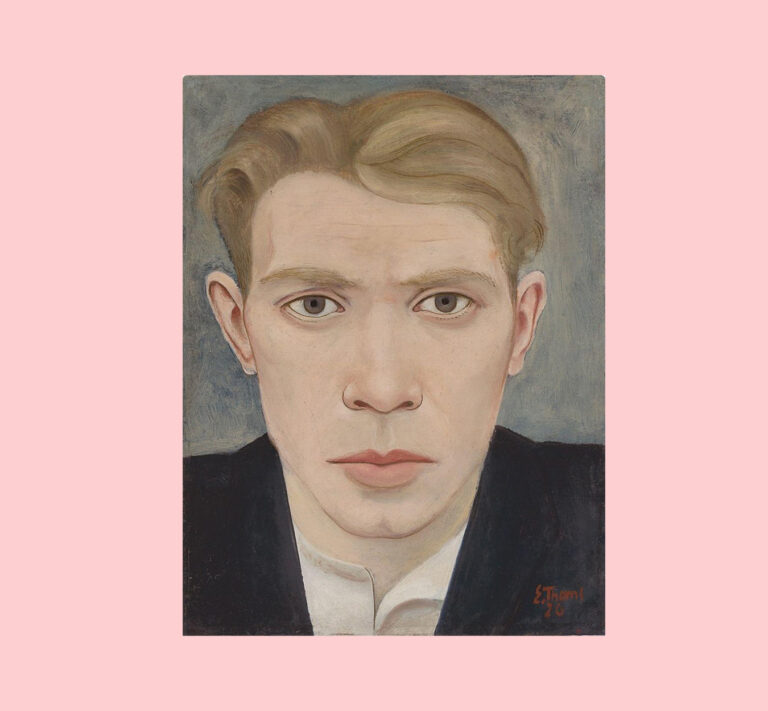

Ernst Thoms, Self-Portrait, c. 1926.

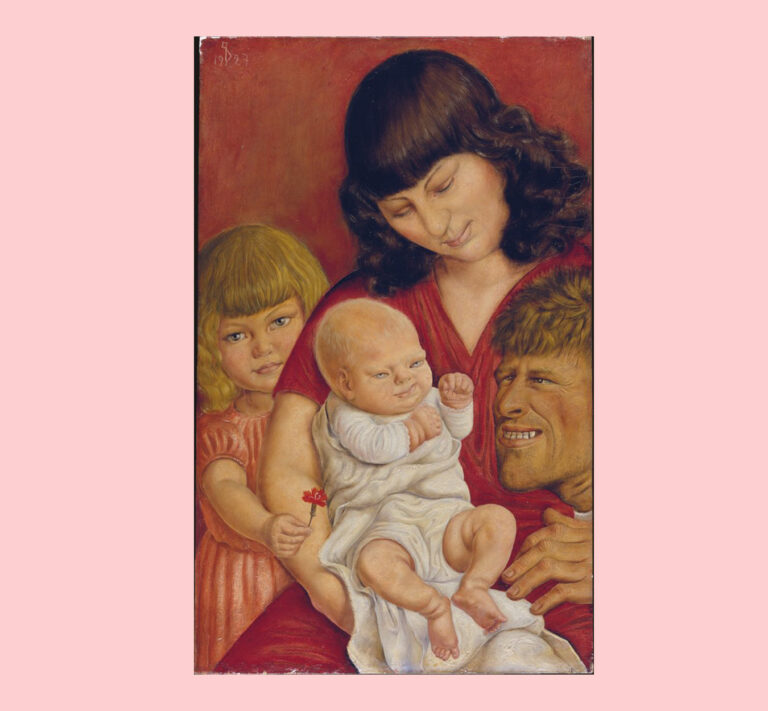

Otto Dix, The Artist’s Family, 1927. Oil on panel, 31.5 x 19.69 in., Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main, DE.

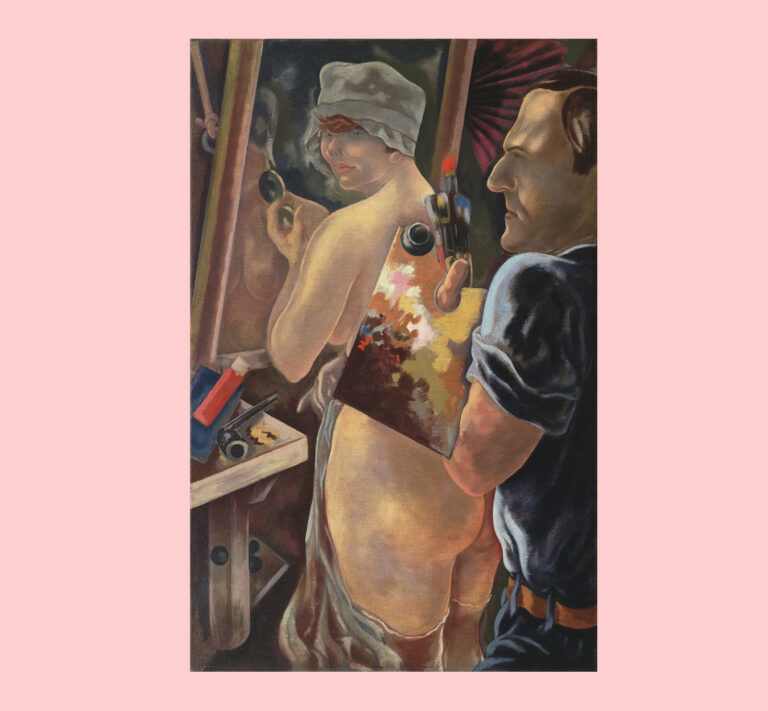

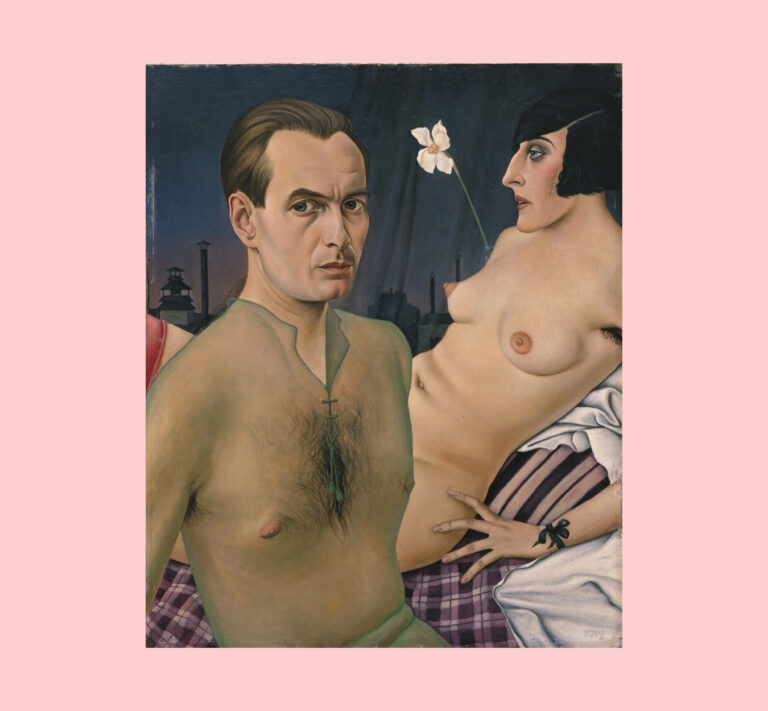

George Grosz, Self-Portrait with a Model, 1928. Oil on canvas, 45.12 x 29.76 in., MoMA.

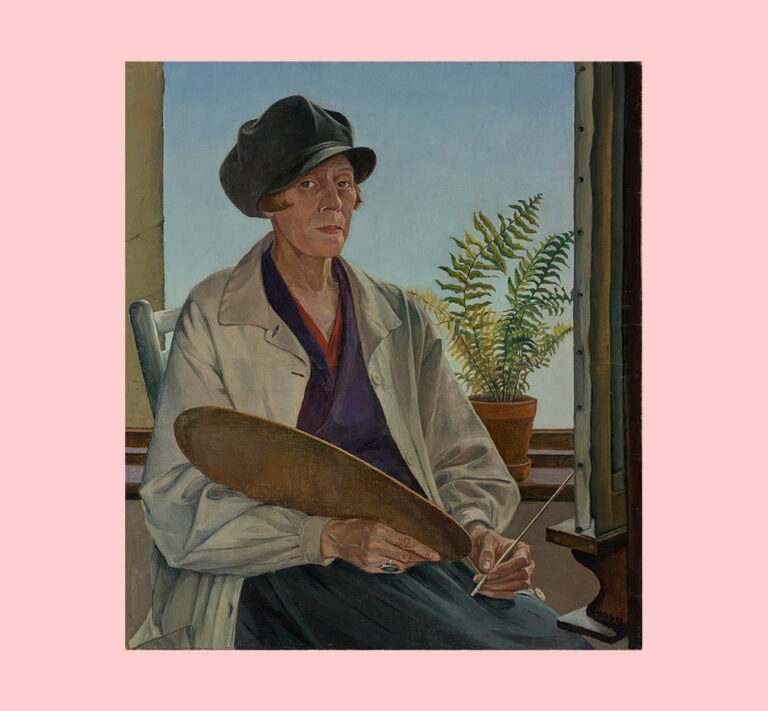

Käte Hoch, Self-Portrait, 1929.

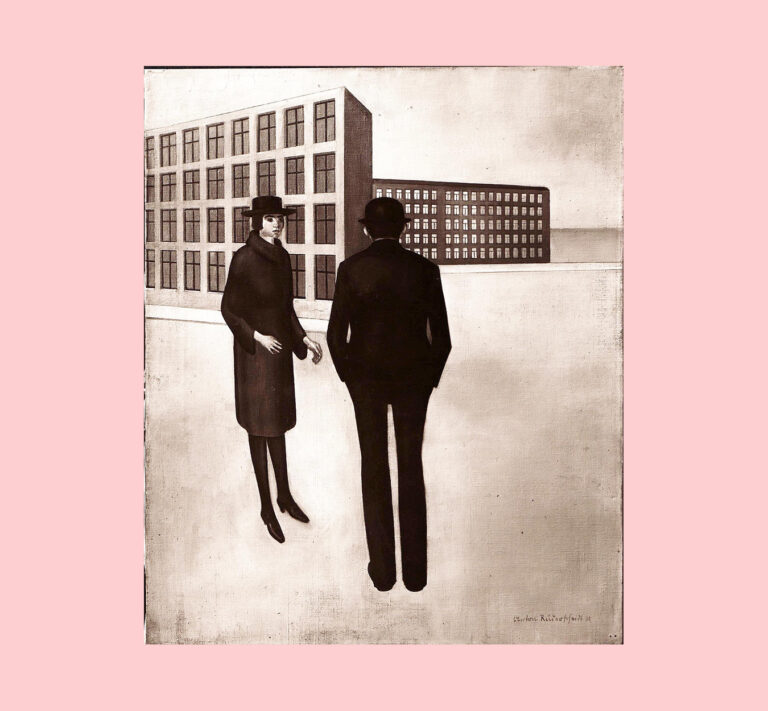

Anton Räderscheidt, Encounter II, 1921. Oil on canvas.

Christian Schad, Self-Portrait, 1927.

Baishya, Anirban. “Selfies: #namo: The Political Work of the Selfie in the 2014 Indian General Elections.” International Journal of Communication, 2015.

Blom, Philipp. “All Eyes: Self-Portraiture, the Collapse of Truth, and the Birth of the New Man.” The Self-Portrait: From Schiele to Beckmann, edited by Tobias G. Natter. Prestel, 2019.

Borzello, Frances. Seeing Ourselves, Women’s Self-Portraits. Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1998.

Bridle, James. New Dark Age: Technology and the End of the Future. Verso, 2018.

Brilliant, Richard. Portraiture. Reaktion Books Ltd, 2013.

Goffman, Erving. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. Prentice-Hall, 1963.

Hall, James.The Self-Portrait: A Cultural History. Thames & Hudson, 2014.

Jurgenson, Nathan. The Social Photo: On Photography and Social Media. Verso, 2019.

Pointon, Marcia. Portrayal and the Search for Identity. Reaktion Books, 2015.

Rogoff, Irit. “The Anxious Artist – Ideological Mobilisations of the Self in German Modernism.” The Divided Heritage: Themes and Problems in German Modernism, edited by Irit Rogoff. Cambridge University Press, 1991.

Seymour, Richard. The Twittering Machine. The Indigo Press, 2019.

Stoichita, Victor I. The Self-Aware Image: An Insight Into Early Modern Meta-Painting. Brepols Publishers, 2015.

Zhao Pan, Yaobin Lu, Bin Wang & Patrick Y.K. Chau. “Who Do You Think You Are? Common and Differential Effects of Social Self-Identity on Social Media Usage.” Journal of Management Information Systems, 34:1, 2015.