A blue blip appears on my phone. Glen Baldridge is messaging me from Great Falls, Montana, where he was raised. He’s using the encrypted Signal app, not because he’s paranoid about surveillance, but because he’s roaming, off the grid, out in that vast and sparsely populated range that captures the mythic American West. His messages are composed of the hidden texts within his new series of paintings: Buzz Kill, Harsh Toke, Dark Daze.

Baldridge has lived in cities for his adult life, but his rural youth has uniquely tuned him to the strange and undefined spaces where culture and nature dissolve, comingle and lose definition. His work often peers into remote places: where the woods begin; where darkness shrouds the edge of town; under floorboards where secrets are kept; in the junk culture of road-stop gas stations, head shops and Dairy Queens; in online chatrooms and car-culture fetish websites.

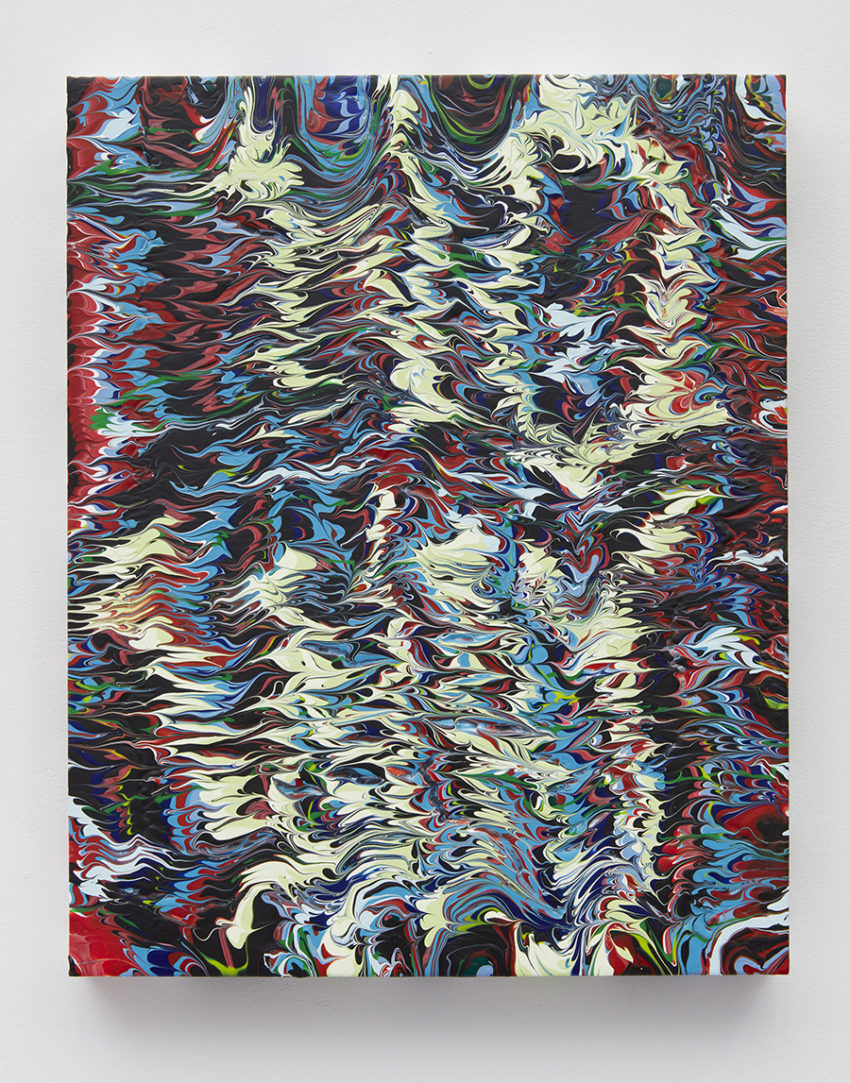

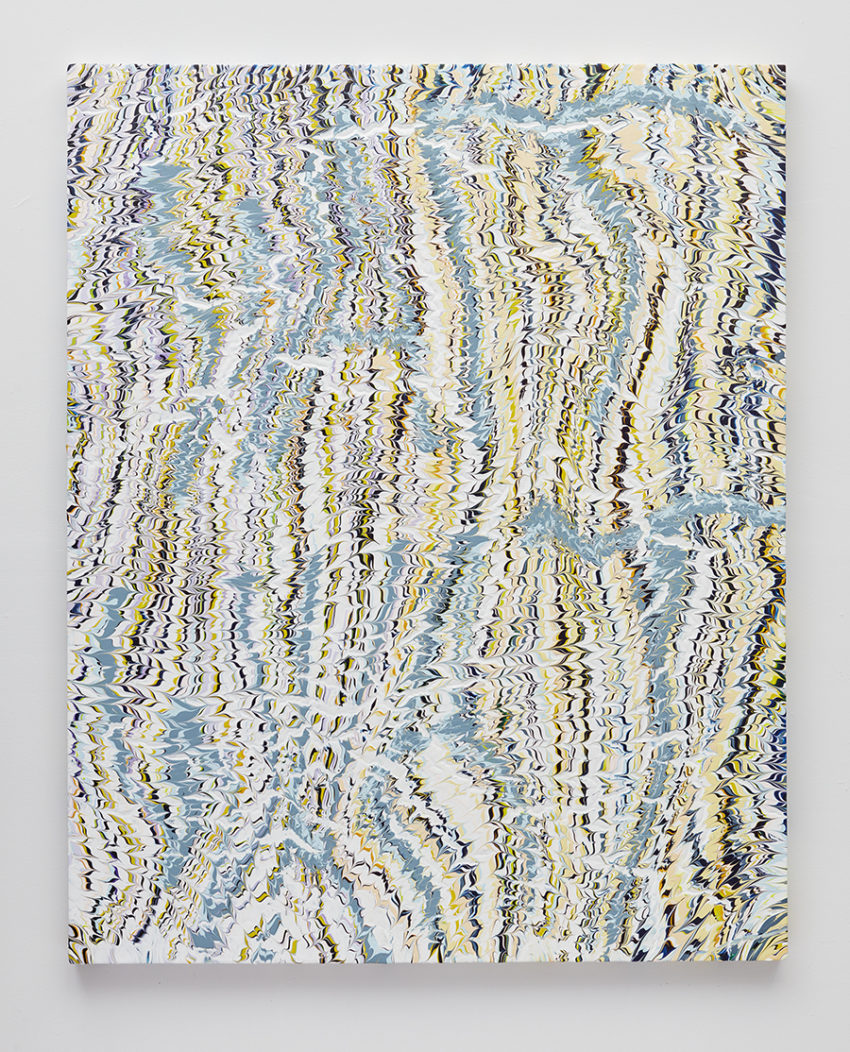

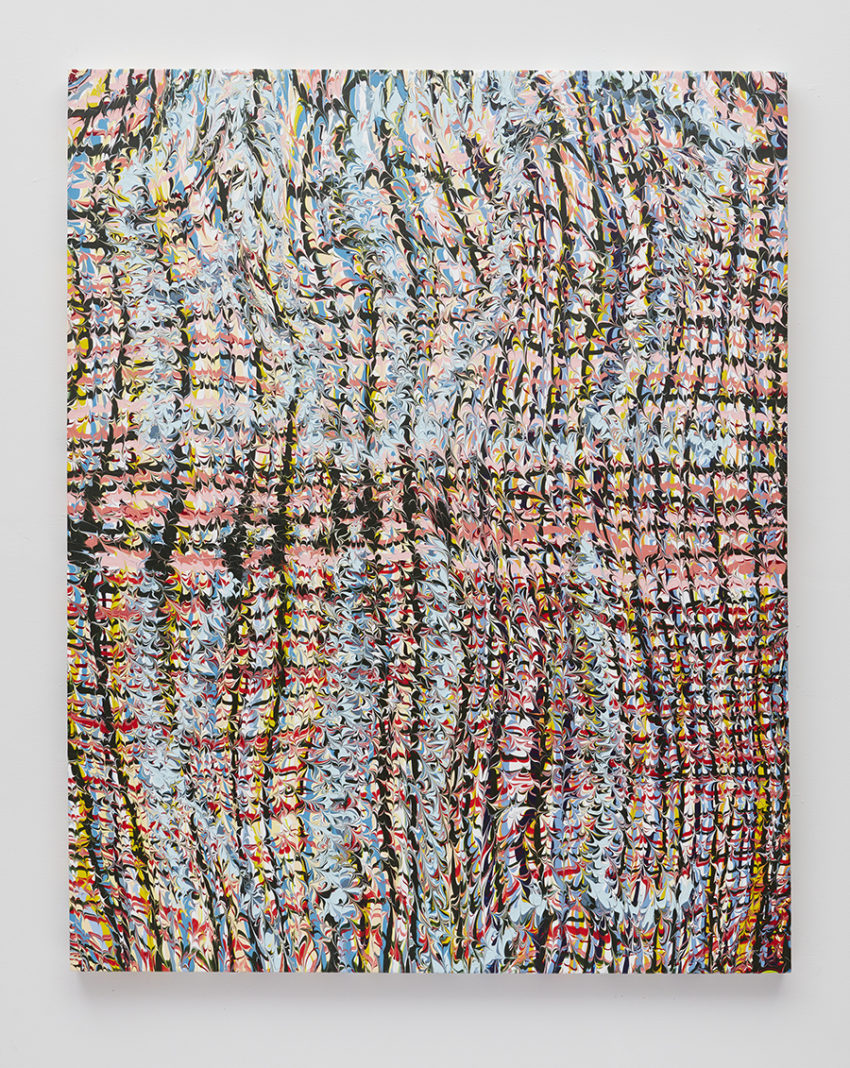

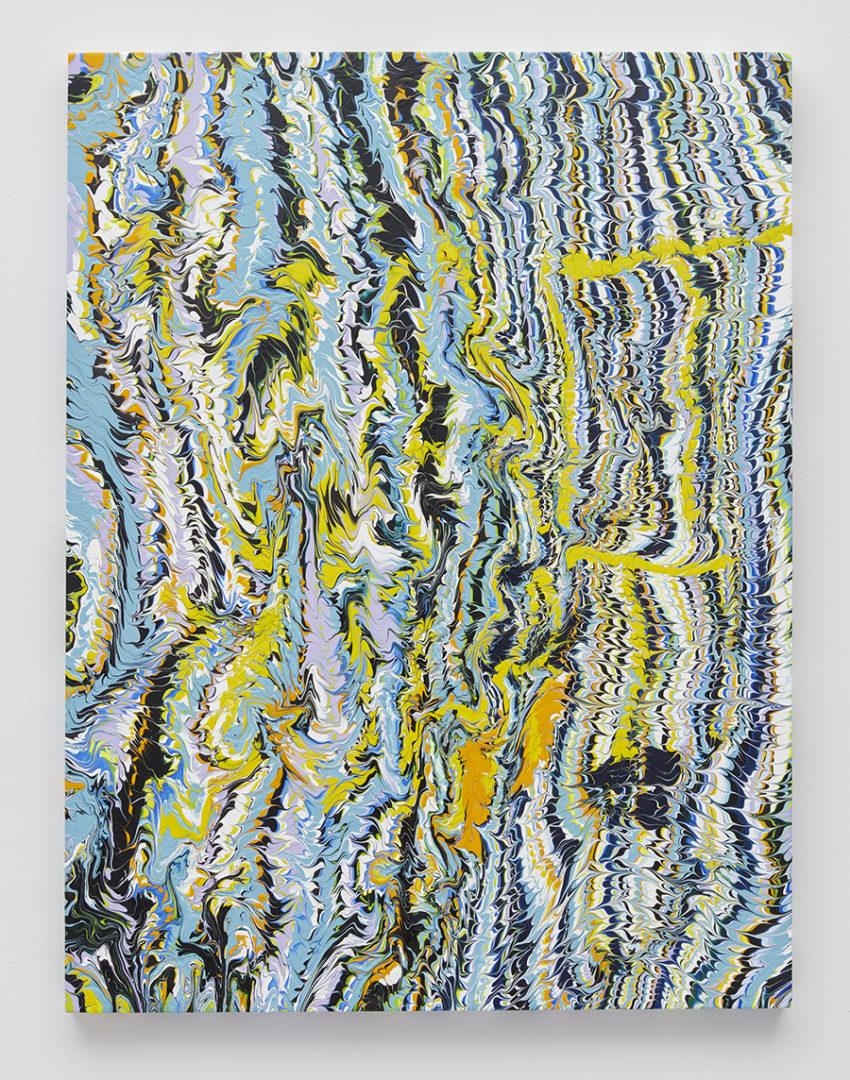

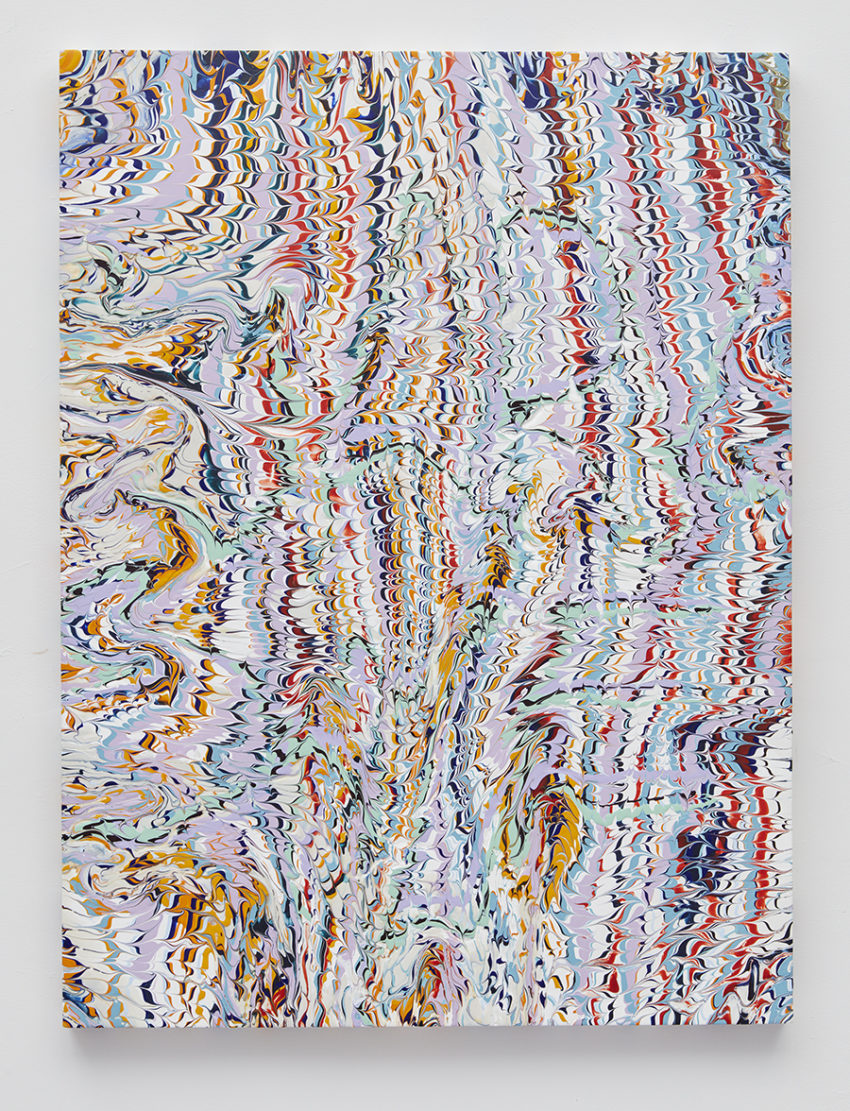

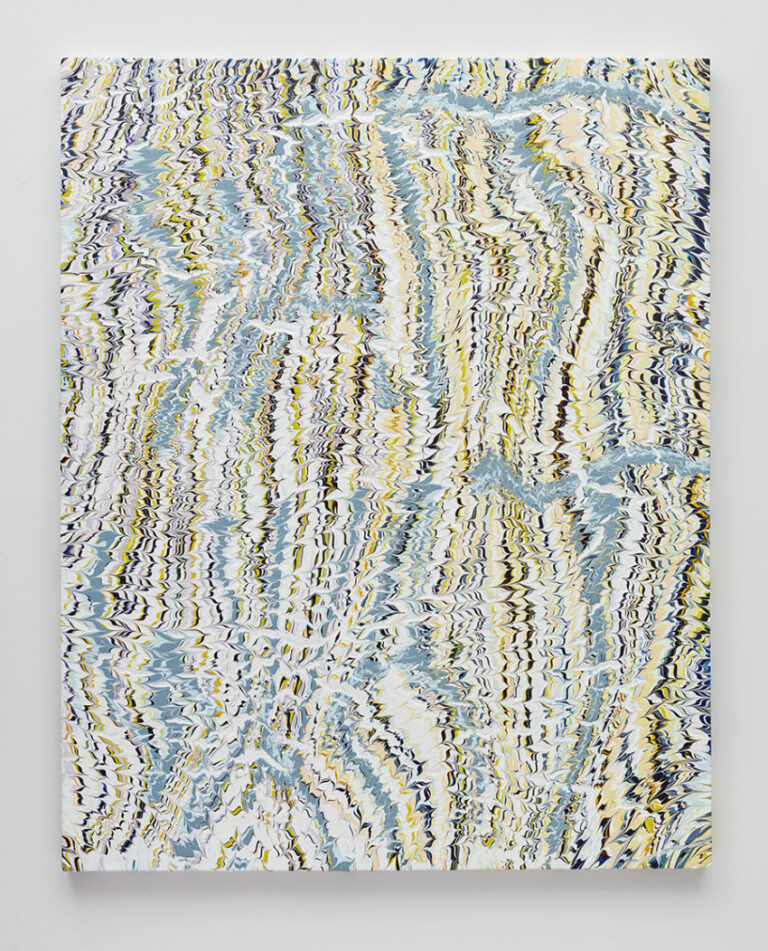

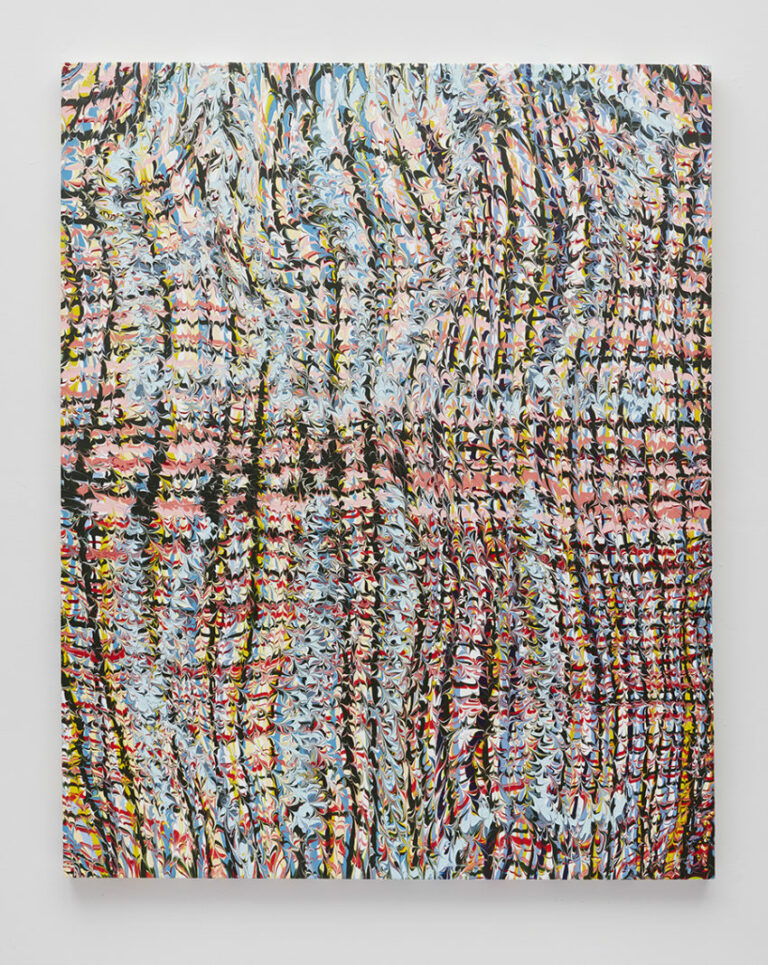

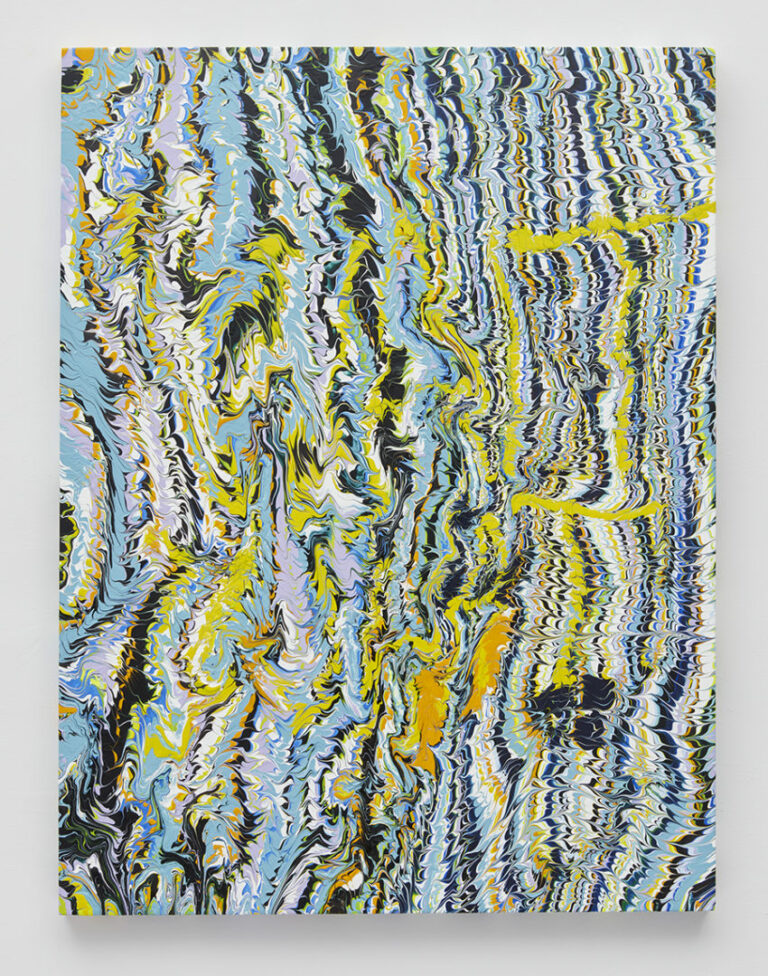

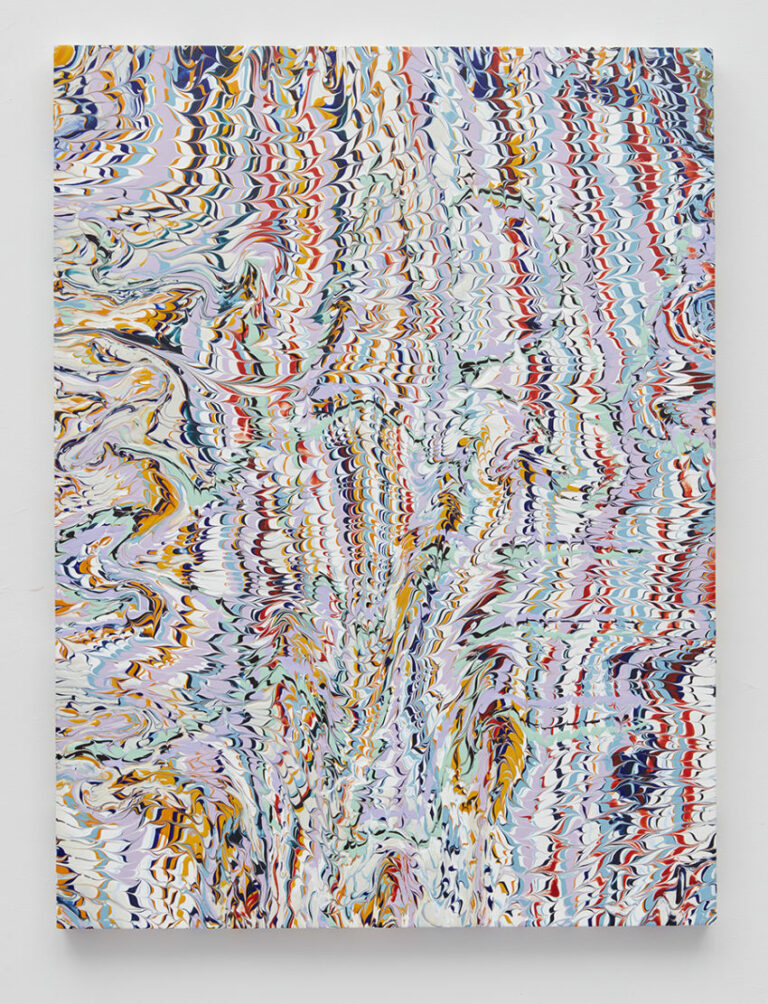

A distinct change has occurred in Baldridge’s latest work, and it is not merely his departure from the agitations of his printmaking training. He has stepped fully into the messy field of all-over expressive painting, bolstering his text-based work with bravado. The paintings have no foreground or background. They depict a jungle of oozing color hiding an awkward script below, literalizing the aphorism “unable to see the forest for the trees.”

These works derive from Baldridge’s continued mining of traditional artisan techniques — in this case the marbled paper tradition that spread from Asia to Europe, and was often used as a method to prevent against counterfeiting documents or spreading false information. Those skilled in developing the “secret knowledge” of the aqueous suspension of sinewy pigment across a field of paper became in demand as books began to be printed. Marbled end-leafs became a bridge between container and content, a bookend for the dissemination of civilization’s achievements.

In Baldridge’s rendition, the technique has lost its connective tissue. It has become the purview of psychedelic cake-makers and pot-paraphernalia. Embedded within the dank depths of acrylic polymers and pigments are base phrases that could be described as “dumb” (although Baldridge is keenly aware of that word’s double meaning as both stupid and inaudible). Burbling below the swampy surface are darkly comic nonsense phrases (World War IV, Rat Bite, Fun Funeral) that capture America’s descent into primal incoherence. Trumpeting the noise of our era, Baldridge cannibalizes received wisdom and pop culture into a riotous brew.

Yet these paintings are no buzz kill for the eye. They are humming with luminous intensity, delirious in composition, deciduous in saturated color. Baldridge’s fresh crop will make their New York debut under the exhibition title Dream Burner, connoting a soothing haze. Yet the dreamy connotation collapses with a Google search, revealing Dream Burner to be the infamous Brooklyn head shop that sold a synthetic marijuana called K2 that gave users such a stupefying high that the shop’s neighbors began calling the nearby area “Zombieland.”

With sinister humor, Baldridge laces his paintings with traps to reflect the swamp of our culture, so bent on mindless self-satisfaction that it has become numb, desensitized and burnt out.

Writing about it reminds me now of visiting Glen in his studio.

“What does this one say?” I ask, squinting.

“Wait what,” he deadpans.

“Wait, what?” I ask, because I think he just asked me what I asked.

“Wait what.” He sets the trap again.

“Wait, what?” I ask again, lost.

And if I didn’t know him well, we could speak this way for hours, saying the same exact thing, but never comprehending what the other one means.

– David Kennedy Cutler, October 2017