A heart murmur is a sound, such as whooshing or swishing, made by turbulent blood in or near your heart. Despite having a sweet sounding name they are potential harbingers of dysfunction or even death; they are kind of soft and dangerous. At the same time they are a moment where the body is able to speak directly to the self; the somnambulant object is momentarily granted consciousness via a kind of morse code. The works in this show also possess a type of soft danger and seek to speak to you beyond their corporeal capacities. They are generally scaled down in size and seem to wield various special powers: alchemical, spiritual, subversive or metaphysically reified. As a whole there is a kind of quiet menace to the grouping, a sooty darkness covers much of the work and a sense of paranoia and fear cohabitates with the otherwise passionate intentions of the makers.

Heather Bursch invades the antiseptic and indifferent space of the contemporary art gallery with the language of high-end luxury remodeling. Borrowing materials and ideas from her job as a faux-finish painter the artwork seems to participate in a playful critique of both the skin-deep idealism of contemporary art and the gilded facades of the speculative real estate market. At the same time there is a kind of earnest finesse to the work that, along with a sensitive jerry-rigged workmanship, places her hand into the mix as well. People may be implicated throughout but not necessarily as problems, more so there is an understanding of the need to reconcile the utopian standards we strive for with the dissonant and unideal situations with which we must live.

Drew Kohler paints vibrant fever-dream hallucinations of extraterrestrial mudmen engaged in inexorable copulation. Hard won formal rigor is wrapped tightly around the subjects, clothing them in a sullied chromatic brilliance. Rendered in a palette of almost exclusively spectral colors (pure tones of the rainbow), but mixed with a kind of dirty intensity, their compositions are held in perilous equilibrium. In moments where the paintings might seem to falter they bow their heads in an appeal to pathos, requiring a certain amount of love in order to function. Color here loses its earthly meaning and becomes extrasensory, like seeing the world through Monet’s post-cataractic lensless eyeballs and then taking psychedelic drugs; the opsins drenched with an ecstatic radiation that produces its own kind of thermal imaging.

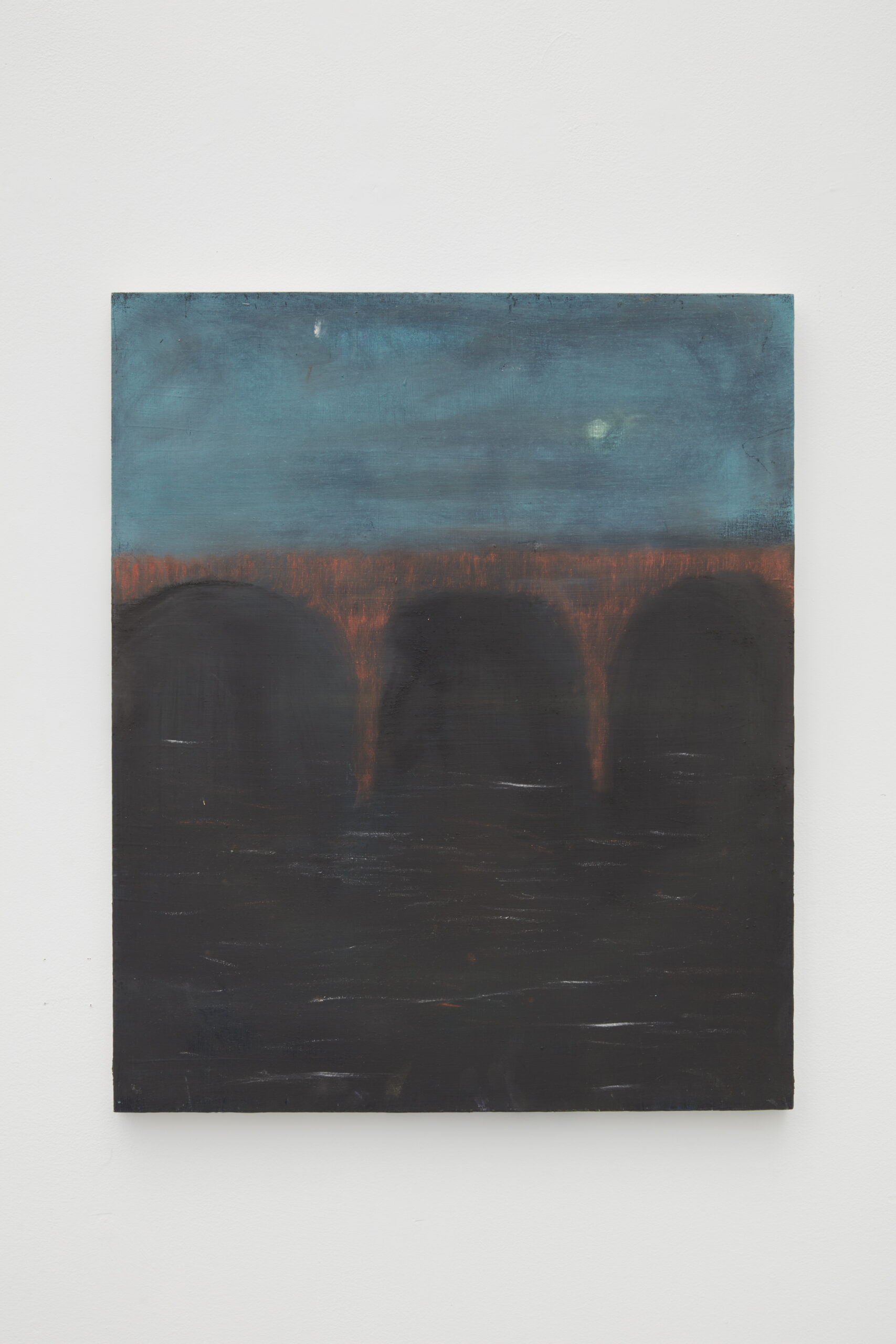

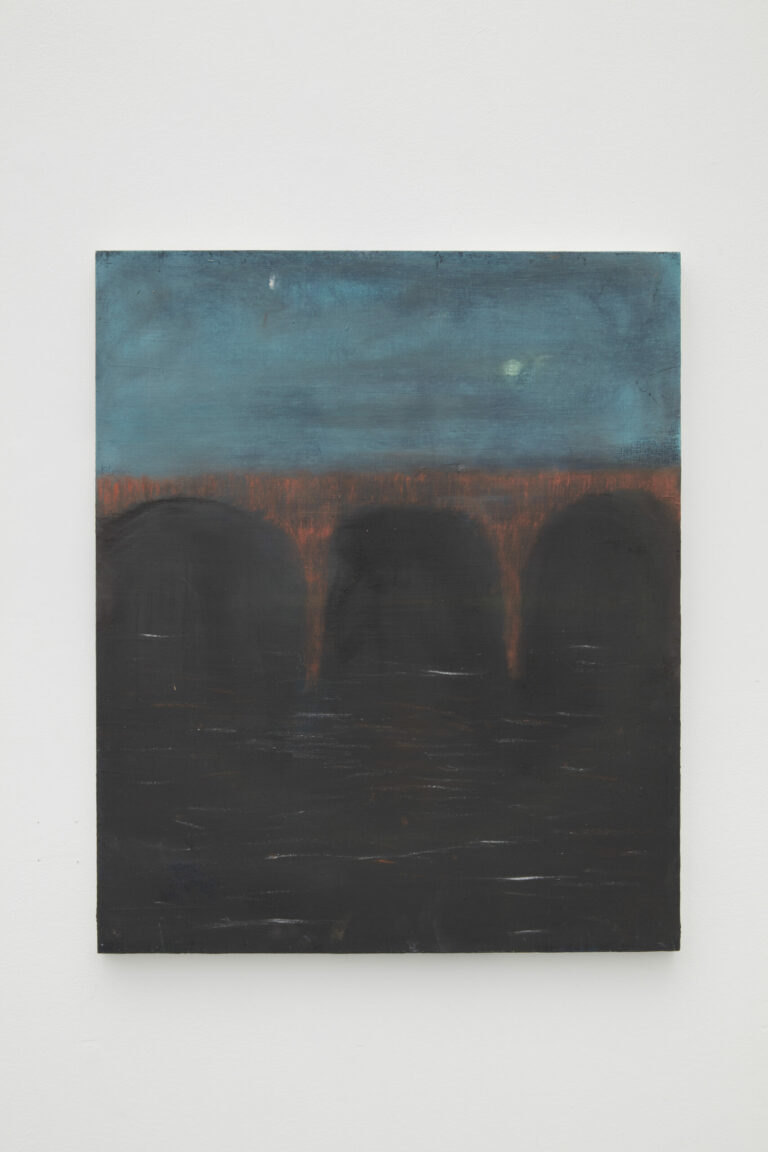

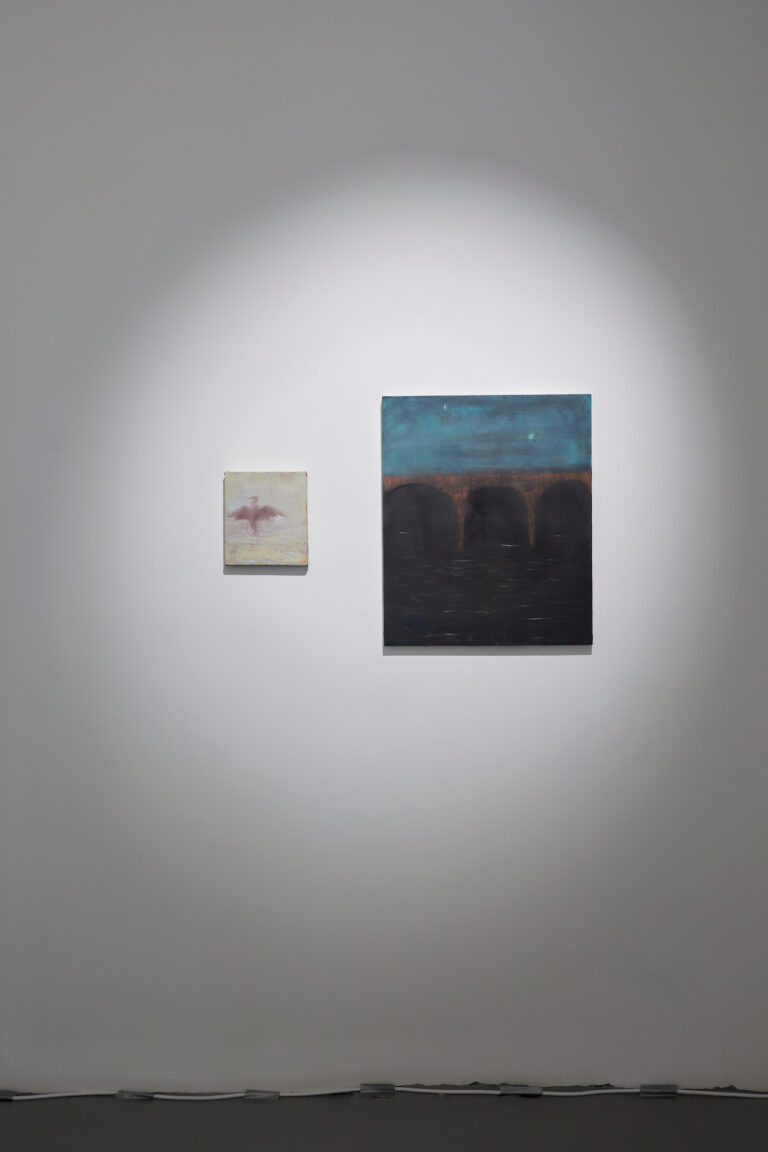

Elisa Jensen peers into the dark void which has enveloped recent years and attempts to pierce it, clarion like, with the power of magical cantrips. She paints, heedless of cynicism, as a kind of modern day

shaman; a last resort plea to some older, perhaps wiser, power in an attempt to change reality through sheer force of will. The paintings act as conduits for an emotional energy which is used to perform a type of realism whose verisimilitude is gauged less with mimetic representation than with the reification of pure feeling. There are sensations of dismal optimism in the form of an ascendent phoenix, tiny and faint as if drawn into the wet paint by wisps of smoke, and a dark bridge to somewhere, seen from the banks of a pitch black river, suggesting that perhaps an escape is possible though dark and far away.

Nicholas Sullivan employs a kind of poetic alchemy in meticulously crafted, anachronistic recreations of stoves, furnaces and other heating apparatuses. Sublimation is a word used to describe the transition of a substance directly from a solid to a gas without passing through a liquid state, but it also refers to the channeling of base desire into productivity, a central concept for theorizing the creation of artwork. Such meta-language play continues with the construction of the works materially; though they depict the appearance of blackened iron they are in fact constructed entirely from newsprint and charcoal, materials which are familiar to students as foundations level art supplies in life drawing classes. The quixotic didacticism of the work is so finely melded with their materials that it begins to oscillate wildly between formal and linguistic dimensions, causing them nearly to implode.