The Holocaust has not been a viable subject for art. A handful of artists have built monuments to it, but the subject has always seemed too large and too terrible, and the consensus was that whatever images it inspired would appear trivial and anecdotal alongside the evidence of photographs and films. How could art deepen our understanding of a subject about which it seemed that there was nothing more visually to be said?

It now appears, however, that for Jewish artists who lived through World War II, something has changed. At the same time that the Jewish Museum was preparing its current installation of the plaster version of George Segal’s 1983 sculpture of the Holocaust, commissioned for a Holocaust Memorial site in Lincoln Park in San Francisco, the painter Cleve Gray was working in his Connecticut studio to complete a series of works in which the ghosts of the Holocaust were encouraged to stand up and speak.

And in North Carolina, a professor of psychology named Irwin Kremen was putting the finishing touches on a series of abstract collages in which some of the most familiar emblems of the Holocaust were given the weight of stanzas in a narrative poem. The collages are on display at the Rose Art Museum of Brandeis University through Oct. 27.

If the Holocaust has become a viable subject for art, Segal is a major reason. His sculpture of 10 corpses and one survivor – at the Jewish Museum through next Sunday – demonstrated that the subject could be approached with intelligence and dignity. The sculpture’s pile of bodies and strips of barbed wire also suggested the degree to which images identified with the Holocaust have become part of the Western imagination. The striped prisoner’s uniform, yellow star, boxcars and gas chambers are images everyone carries within him. What has been needed is something that could detach those images from the enormous events that produced them just enough to make them accommodate private as well as public experience.

Kremen is one of the first artists who has been able to turn images identified with the Holocaust into metaphors. There are 11 collages in his Holocaust or “Re’eh” series, which has been added to a traveling exhibition of 31 of the the artist’s collages organized by Robert T. Buck and Barry Walker of the Brooklyn Museum, where the exhibition opened last spring. The 31 collages will be at the Allentown Art Museum in Pennsylvania from Nov. 10 to Jan. 5. The Re’eh” series will be shown only at Brandeis.

All the collages are composed of scraps of paper, most them gleaned from American and European walls. Kremen is attracted by patterns, colors and textures, sometimes by numbers and letters. He is not interested in new paper, filled with illustrations and words, but rather in ruins – paper that has dissociated itself from its original function and now wears its own “unduplicable” history. Making the collages involves in part allowing the “experience” written into the papers to emerge.

The collages are usually rectangular and rarely busy. They come from walls and they suggest walls , walls that peel, crack and break yet continue to fill up. The collages seem to be guardians of a secret. There is a sense that within and between the layers of paper there is something we know but can only glimpse.

Kremen deals with the subject of the Holocaust with extreme restraint. The “Re’eh” collages are declarative, but they are also silent. The subject is huge, but the works are intimate and even tiny. The emotional content is dramatic, yet the collages are abstract, and they move with the radical slowness of a frieze. They are like images we have looked at a thousand times, yet never seen.

Kremen is himself an unusual story. He is a 60-year-old professor of psychology at Duke University with no formal art training who has remained completely outside the gallery system. Before he studied psychology, he was a literature student at the experimental Black Mountain College, near Asheville, N.C. He was a classmate of the painter Kenneth Noland, and he was exposed to the paintings and theories of Josef Albers, who encouraged his art students to use any visual material that inspired them.

At Black Mountain, Kremen studied literature with the celebrated potter and poet M. C. Richards. Through her, he met Merce Cunningham, John Cage, with whom he has maintained steady contact for more than 30 years. It was M. C. Richards who encouraged him to begin making collages in 1966 when he found himself questioning his intellectual method. He was suddenly convinced of the need for artistic as well as scientific knowledge.

If Kremen’s collages mirror the way he ”twists and turns ideas analytically from multiple perspectives” in his approach to philosophy, the “Re’eh” series also reflects his doubts about academic knowledge. For example, academic psychology is filled with numbers and statistics. While they have a useful purpose in accumulating and ordering information, they also tend to reduce human beings to abstractions. Kremen is both highly respectful of systematized thought and scientific method and very wary of it. The Holocaust series is extremely sensitive to the dehumanizing effect of numbers and constantly aware of the consequences of systematic thinking pushed to its limits.

Kremen began tearing worn and abandoned paper off city walls in Amsterdam in 1969. Since then he has gone to Europe almost every year, educating himself in the art of the past and gathering supplies. “I’m hardly happier than when I’m roaming strange new streets with my vinyl collection case and my surplus United States Army knife to help me pry paper from walls, boards, kiosks, posts, windows; from stone, mortar, wood, steel, glass.”

At some point he takes the papers he has accumulated and “unpacks” them, by which he means that he dumps them out. Then he observes and begins playing with them. When he has a pattern that pleases him, he will give it a temporary adhesive, clamp it under plexiglass, photograph it, then leave it, sometimes for years, until just before an exhibition. Then he will finish them, cutting, tearing and trimming the edges, sometimes changing the collages completely.

Unlike most collagists, Kremen does not use paste or glue. Rather, working with bifocal magnifying lenses, he uses “tiny bits of gossamer-like Japanese paper for hinges and a conservationally tested copolymer as adhesive.” The process is slow and arduous. It involves not only hinging together the most fragile and minuscule dots of paper, but deciding where the hinges should go. As a result of his method, however, edges retain their integrity, and between the paper there is a sense of air. Kremen also mounts and frames his collages. Every step in the process, including the conservation, he takes himself.

All this helps to explain the freshness, clarity and sometimes the monumentality of his work. Kremen says that in Hebrew, “Re’eh” means “see!” It is intended to refer not just to vision, but to the whole perceptual process. “Look!” “Witness!” “Remember!” he says. “Hold in mind an event that should not fall away from consciousness.”

The narrative cycle begins with “Im Lage,” which is a little more than three inches square. It contains paper with horizontal stripes, which make the collage look like a page out of a medieval manuscript whose text has become illegible. But the stripes also bring to mind a prisoner’s uniform, and the horizontality suggests processional movement.

The next collage is called “The Inconsolable.” It is large, and it seems to be bleeding black. The top sheet of paper is black. Underneath is a black mimeograph master sheet. The master sheet looks like an old ledger, but names that were once written on it have vanished. Only the lines are left.

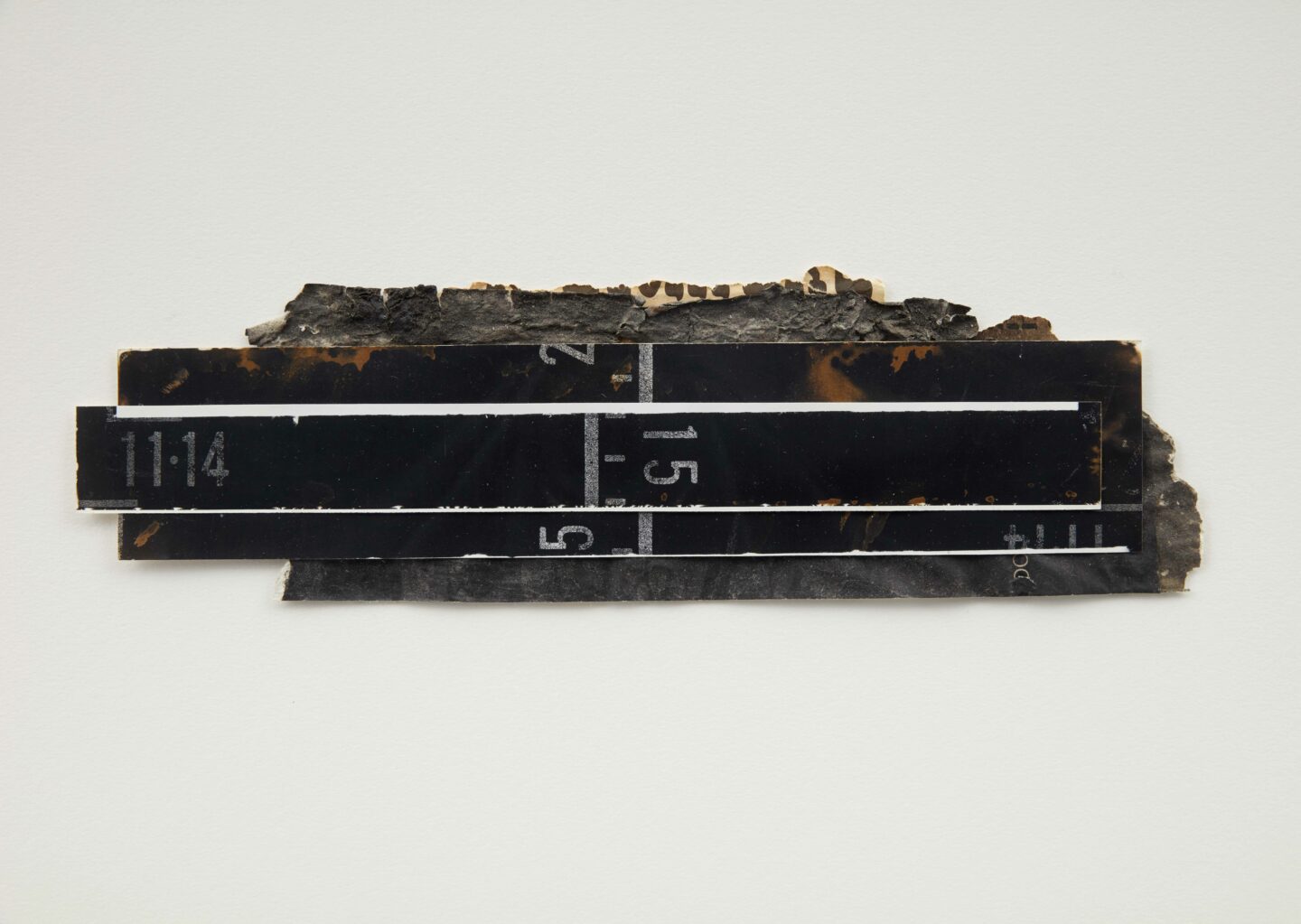

“Transport” is the largest horizontal block in the series, more than 18-inches wide. It suggests a boxcar, rust-colored, faded and – like so many other images in the series – burnt. At one point, behind the front wall of the car, there is a spot of white holding a few almost invisible broken letters. The letters suggest words, which evoke a human presence that has almost been silenced but is still determined to speak.

In “Panathenaic 807985,” the patterns of the paper bring to mind the frieze on the Parthenon, only here individualized human movements are identified not with gods and heroes but with numbers. The lines running down the paper also suggest Etruscan tomb painting, which was made for the dead. The reference to ancient Greece both labels the camps a debasement of culture and suggests the ability of high culture to help bring order and meaning to events far removed in purpose, place and time.

The largest collage, “The Three Graces,” continues the dialogue between one of the peaks and one of the nadirs of civilization. The paper here is white, almost like a doily, but there are traces of yellow. The patterns suggest a slapstick trio wearing fashionable hats and kicking their feet even while they seem to be disintegrating before our eyes. The dancelike, musical quality to the movements, which echoes Picasso’s ”Three Musicians,” suggests the crucial importance of music to Jewish culture, even in the camps.

In the collage “And by Gun,” Kremen uses photomechanical transfer paper left over from a photographic reproduction of a collage. This work, too, is monochromatic and marked by numbers. The work suggests a gun. Perhaps there is a pun here: shooting meant death, but ”shooting” with a camera created a record that enabled something to survive. The paper is a negative, which reinforces the sense throughout the series that we are looking at something that now exists only in shadows and traces.

In the final work, “Unto Dust,” specks of paper seem like ashes that have been blown out of a fire and fallen onto the white backdrop. But the puffs of paper also coalesce into a figure, who, while ascending seems also to be dancing and moving forward proudly, like a Picasso “Dryad.” In this silent, demanding and totally unsentimental series, Kremen has taken a body of images that has seemed definitively public and made us feel that we can hold them close to us and build with them and make them our own.