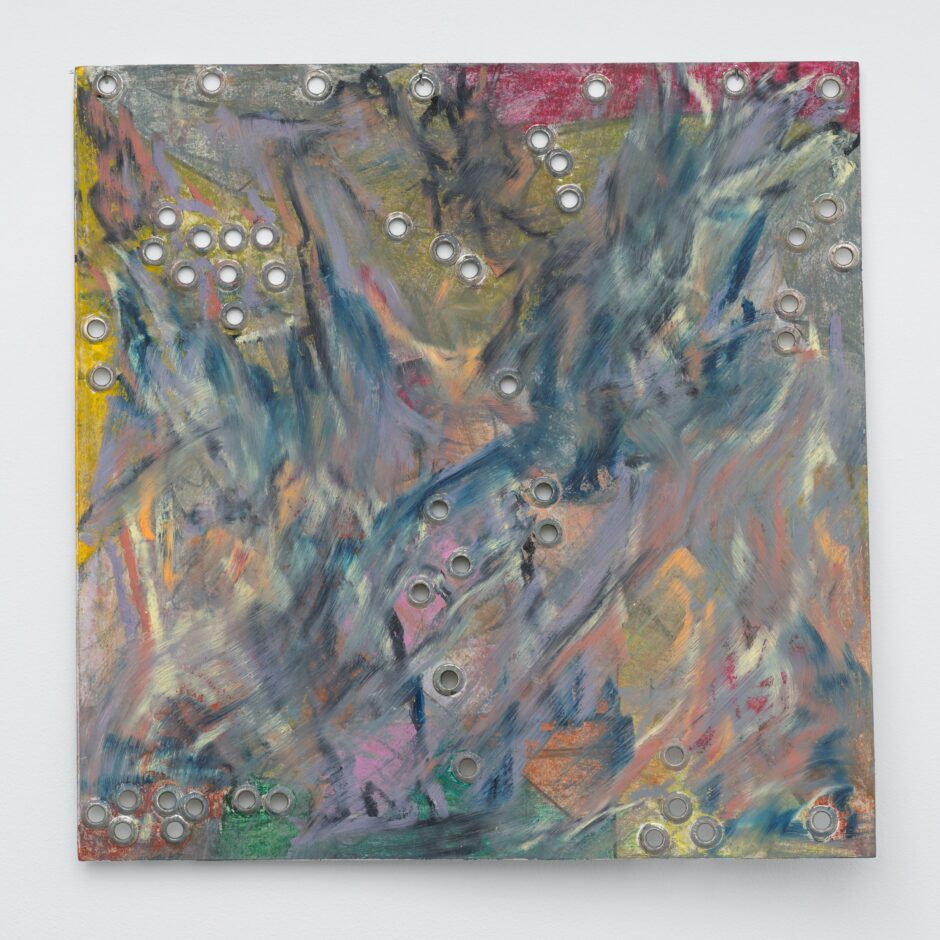

by Louis Block, 2021

Each of Kemar Keanu Wynter’s paintings is an urgent compression of color. Wynter applies oil pastel in lines that swirl and smear across the paper, so that his compositions are bound by the density of their own centers rather than any external structure or gravity. An entire language of marks seems to unfurl and come back into focus.

The work’s sense of urgency comes from the grid of cardstock underneath the thick pigment—a substrate that is malleable and modular, as if each successive sheet was added as the painting morphed and expanded. Fields of color skip and blur across those paper borders, and the underlying grid is often off-kilter and misaligned: more evidence that form was subsumed by process, that the whorl is not what is being described but the shape that describing takes.

The effect is overwhelmingly topographic. Wynter’s muscular passages of color become rivulets in bird’s-eye view or close ups of hair, lightning storms passing over the landscape. The massive Macaroni Pie (2021), the only work with a horizon line, seems to be composed from a constantly swiveling vantage point—its brown and violet lines transform from tiger’s fur to wheatfield to campfire embers, and finally to a ravishing sunset.

Wynter’s hand is kaleidoscopic, and, like fingerprints, these pictures hold data in their sinewy lines. Each painting is accompanied by a coded missive written in pencil, and Wynter uses a rotational cipher to scramble the messages, so each letter must be shifted by a certain number of places in the alphabet to be read. Here, the number to be shifted is in the hundreds, so the Roman alphabet, like the ever-expanding sheets of paper, becomes another limit to be breached, language orbiting and exceeding its own model.

Deciphered, Wynter’s texts are reminiscences of meals from his upbringing in Crown Heights, each focused on a particular dish, like macaroni pie or Aunt Pearline’s potato salad. There are abundant overlaps between the twinned alchemies of cooking and painting, as in the mixing of magic-seeming powders—spice, pigment—and the tenuous emulsions that hold oils in shape, so it feels natural to seek comfort in these paintings, to turn to them for visual sustenance. But Wynter’s project is not satisfied with that level of easy consumption and demands a longer engagement from the viewer. A primary defense against any quick reading is the fact that the accompanying texts are not deciphered in the moment but must be taken home and worked out without the paintings. In the gallery, they are a jumbled mass of letters like some phonetic monolith, plodding and consonant-heavy on the tongue.

The paintings also contain signals of a certain opacity. They are studded with grommets in irregular patterns, sometimes barely coalescing into lines or grids. I thought immediately of the perforated paper that controls player pianos or blips on a radar uncovered in radial flashes. The artist told me that others had compared the holes to buckshot, but I didn’t read them as acts of violence, rather moments of union. It is important to consider how grommets are fastened to the substrate: though material is cut away, the metal pulls the surrounding surface into a sort of torus bridging front and back, each act of removal bending the plane into another dimension. Along the ridges of those circular portals, the oil pastel had caught and smudged, so each grommet was a site of increased color and density. With the slow shifting of bodies in the gallery, the paper billowed slightly, and those holes projected spotlights or rims of shadow on the wall beneath like swarming eclipses. I was reminded of Francis Ponge’s meditation on bread, how its surface is panoramic, but once “slipped into the cosmic oven” its interior becomes like leaves or flowers “welded by all elbows at the same time.” Wynter’s work is involved in a similar craft, but is ultimately thrown into a linguistic furnace, so what the viewer encounters is twofold: a surface kneading memory into forms, and a broader system of codes that floats between the paintings.

In the accompanying texts, there seems to be an acknowledgement of the paintings’ propensity for metaphor and alchemy in the descriptions of the foods they are named after. A corned beef sandwich is best after a night in the fridge, congealed “into something transcendent,” and stew peas are “ruddy” and “cascading.” Wynter writes s’s in a peculiar way: they recline until the top curve is almost level with the bottom, and the whole letter looks like a horizontal 8 or a piece of metal chain coming undone, as if the muscle memory of writing itself could be disrupted by codes and ciphers.

The rotational cipher is commonly named after Julius Caesar, who used it to code correspondence. In Shakespeare’s rendition, Caesar’s last utterance (“Et tu, Brute?—Then fall, Caesar!”) forms a macaronic phrase, a mixture of two languages in a single line. That same dissonance is felt in Wynter’s exhibition, where the eye and the tongue attempt to reconcile disparate inputs and codes. But prolonged looking is rewarding; the swirls of pastel and grids of paper meeting the ciphers in the act of decoding, each grommet becoming an extension past two dimensions, each letter offering a view into a memory. Wynter’s point is to make the work of language visible, and that this specific language—of food and comfort—is accessed alongside painting feels appropriate.

The root of macaronic is the Latin for stew or dumpling, pointing to food as a primary indicator of cross-pollination. In Wynter’s texts on macaroni pie and fried dumplings there are bracing passages like “a four year old, slotted spoon in tow, lovingly fumbling over blue box,” and “excellence in half ellipses, waning.” It is not too much work, with a simple program, to decipher these messages. Rolling those words around my tongue, remembering the beauty of those reds and yellows and other colors that met in pleated harmony like the spine of an ancient mountain range, it is worth thinking about why those messages were coded in the first place. That the work of reading them is so conspicuous seems like a gift.