“Swallow” is not your ordinary photographic portrait of a tree, which has been a common subject for artists almost from the 19th century start of camera work. Instead of intrinsic majesty within — or over — nature, Mark McKnight turns the tradition into something vaguely ominous and worrying.

The large, black-and-white gelatin silver print in his debut solo exhibition at Park View/Paul Soto gallery shows what appears to be a mighty oak in all its sturdy, leafy, natural splendor, standing grandly at the top of a rise in an open landscape. Yet, surprisingly, fully one-quarter of the image is obscured by a sensuous black swipe of deep shadow across the field, running from the bottom left edge all the way to the right.

The tree stands poised to be engulfed by encroaching darkness — swallowed up and consumed. Flooding the lower register, the shadow emerges from where the viewer stands, as if we are already engulfed by it.

Maybe we are the metaphorical source of the shade, projecting darkness into a vision of a tree that is just a remote aspiration. Formally, the dark, velvety smear pulls a viewer close to peer into the scene to see what, if anything, is going on beneath the lowered limbs of the sheltering tree.

McKnight deftly harnesses standard metaphors — the tree as home to the spirit, sanctuary of the soul; the landscape as an unsullied Eden set against a fraught humanity — and turns them to his own ends. He does the same with photographs focused on clouds in the sky: Big, fluffy volumes overhead are shot through with vaporous light. Yet, a storm also seems to be brewing, a looming heart of darkness within the ephemeral ether that intrudes on the possibility for getting lost in an idyllic summer daydream.

McKnight has titled the exhibition “Hunger for the Absolute,” borrowed from the book “The Metaphysical Dog,” a collection by revered American poet Frank Bidart. The photographer is 36; the poet, 81. The choice suggests generational passage and autobiographical specificity: Both artists are Southern California born, went to school at UC Riverside, identify as gay or queer, and focus their work on subjective intersections of the spirit and the flesh.

Clenched fingers of one man dig deep into the naked flesh of a second man lying on top of him in a roughly life-size image, their bodies seen in anonymous closeup with just bits of grass at the edges. Expressively titled “Tear,” the word and the image can be read multiple ways — as an ecstatic rending or a deep hurt.

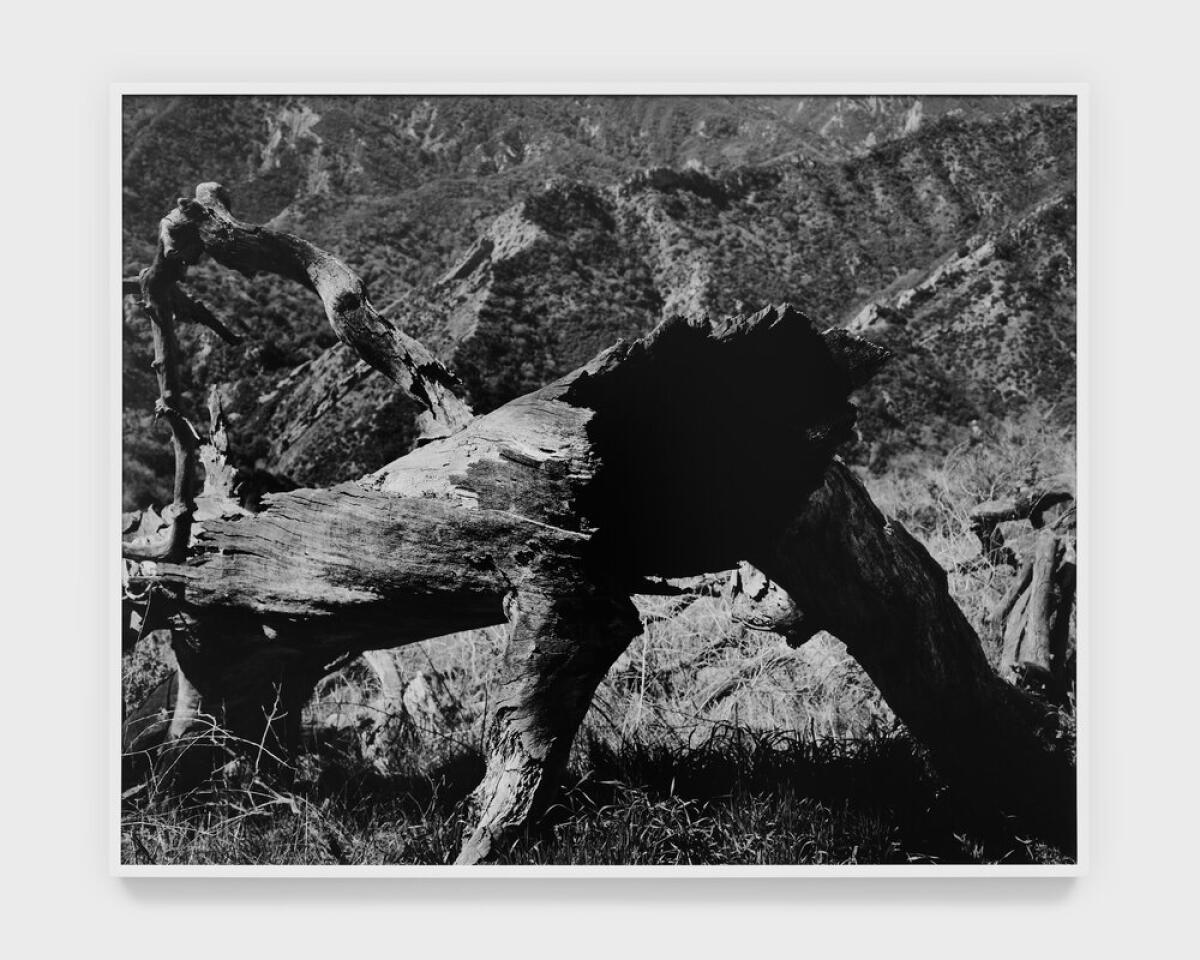

For “Untitled (Tree Void),” the hollowed-out trunk of a decaying tree seems to mimic a figure crouching on its knees in the grass. The landscape as a metaphorical body is again evoked, as it is in “Tear.” Yet these are not the idealized physiques of traditional erotic photography.

A list of the notable photographers referenced in McKnight’s pictures would include William Henry Fox Talbot, Alfred Stieglitz, Robert Mapplethorpe and Laura Aguilar — 150 years of the medium at once embraced, absorbed and reworked. The frankly symbolic, formally attuned, ethereally abstract and potently political all merge in a suite of eight highly engaging photographs.