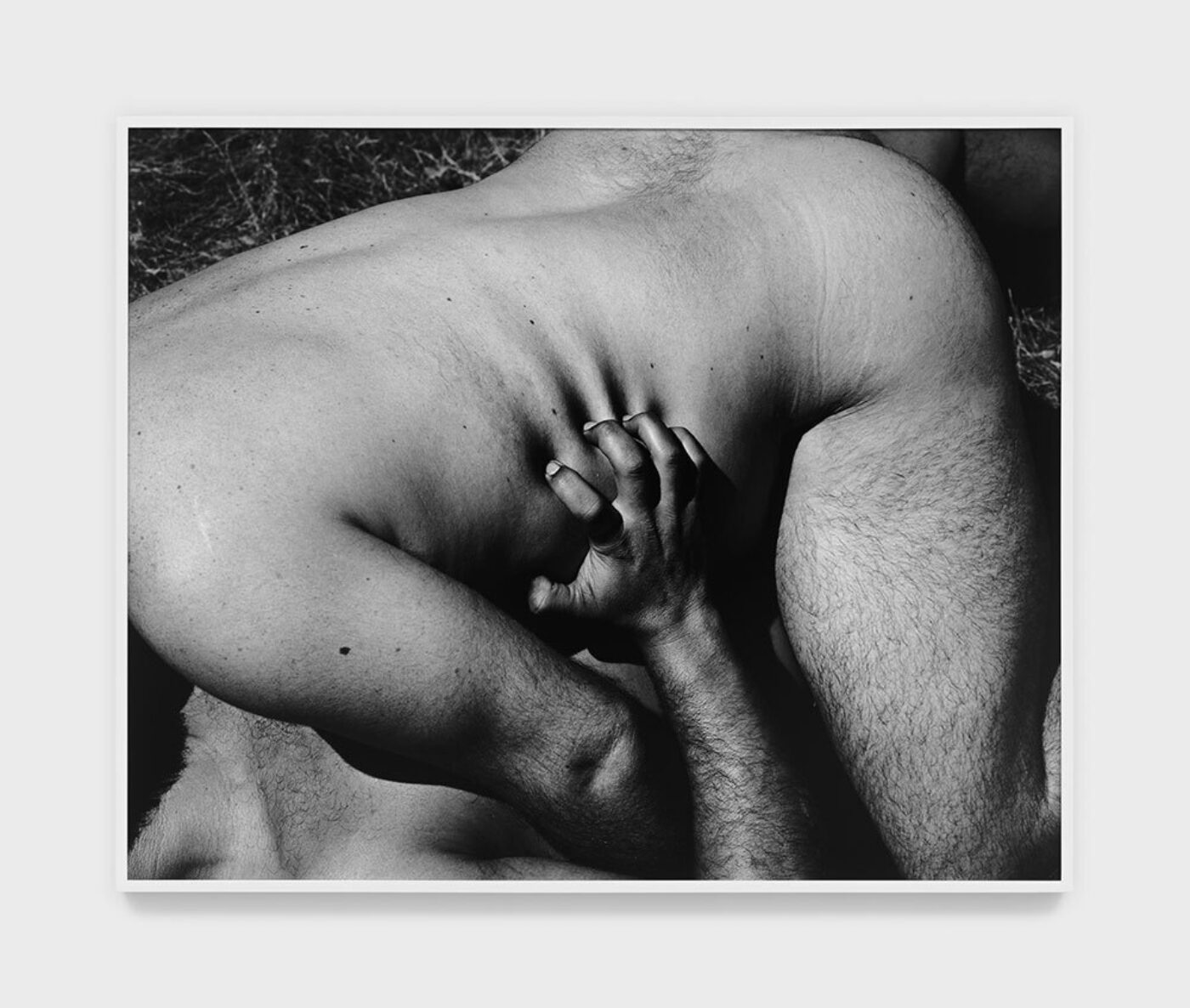

Mark McKnight, Tear, 2021, gelatin silver print, 48 × 60 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Park View/Paul Soto, Los Angeles.

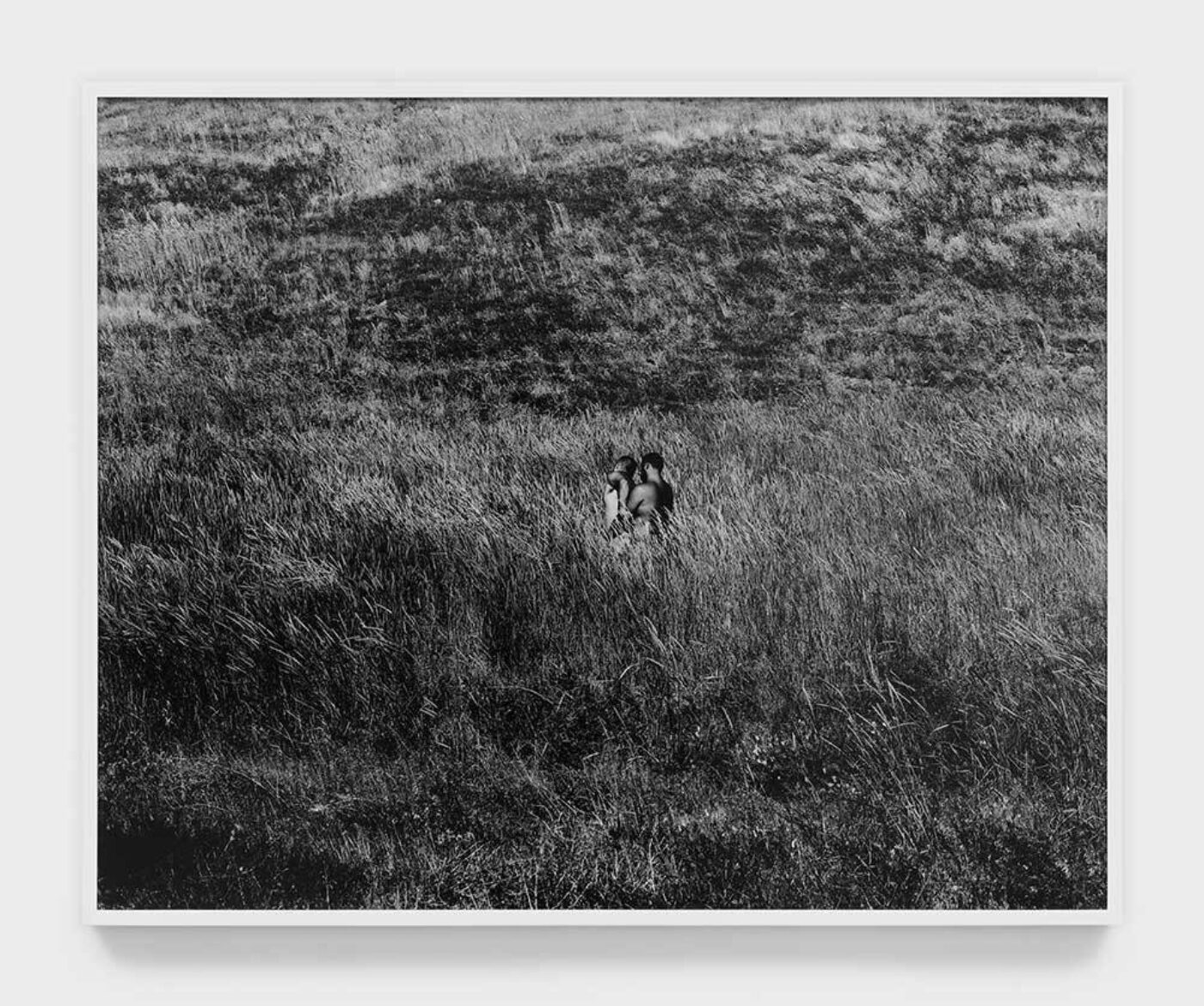

The desert has long been a site for the imagination. It has biblical connotations of temptation and wandering, and when applied to California, it gains a nuanced specificity. California’s shift from 1960s counterculture to Silicon Valley cyberculture proposes a place where one can reengineer oneself. It is where Steve Jobs dropped acid, which was later echoed by his tech-world progeny at Burning Man festivals. Returning to the chaparral of his adolescence, Mark McKnight has spent his adult life photographing human figures in the high desert of Southern California. In his current bicoastal exhibition, Hunger for the Absolute at Klaus von Nichtssagend Gallery in New York City and Park View/Paul Soto in Los Angeles, male figures engage in corporeal, erotic play within a desolate landscape. Their bodies coexist in an environment that is both unforgiving and flourishing. The exhibition, whose title is culled from a poem by Frank Bidart, revels in a sensual overload amid a search for meaning. The photographs alternate between various close-ups of the body and expansive, formal landscape images. These disparate visual strategies result in blurring the lines between human figures and natural environments, transporting the viewer into a psychic landscape of McKnight’s own making.

Looking at McKnight’s work, one cannot help but be reminded not only of our current pandemic moment but also the sense of loss inherited by generations subsequent to the HIV-AIDS epidemic. Although the protagonists of Hunger for the Absolute can be read as affirming, their relative isolation and the conspicuous absence of anyone else suggests a kind of queer, ancestral melancholy in search of “safe space.” McKnight’s work brings to mind Alvin Baltrop who depicted pre-AIDS, disco-era cruising sites around New York City’s westside piers. In Baltrop’s work, the illusion of utopia and “safety” produced by his photographs is ultimately stripped away by them. His images of free sex at the piers are punctuated by a sobering image of a subject being transported away in a body bag. For McKnight, the desert becomes a site of ontological possibility and utopic fantasy at odds with the reality of the artist’s experience growing up there, and his depictions of physical restraint suggest metaphysical bondage to allegorical ends. In other words, he offers an imagined, metaphoric site of freedom that is coupled with images of unoccupied, otherworldly landscapes: a sober reminder that such “safety” continues to remain elusive.

Mark McKnight, Untitled, 2021, gelatin silver print, 40 × 50 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Park View/Paul Soto, Los Angeles.

However, this is not exclusively to entangle McKnight’s images with the past or with the present moment of our current health crisis. First, these photographs are part of a series born prior; and second, that would be far too reductive of their visual power. McKnight’s images of unbridled play have a certain jouissance that seduces the viewer; they are erotically charged without being reduced to mere pornography. One is reminded of eroticists such as Jean Genet who would pleasure himself while writing scenes yet maintained they were not pornographic. McKnight’s images are perhaps closer in their evocation of the dream scene in early Hollywood films where a fantastic wish projection disrupts the normative scenario (think of the films of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, or Kenneth Anger, or South Pacific [1958]). Formally, the works evoke earlier Modernist photographers in which formal experiments with quotidian subjects are recounted with an almost Cubist contrast combined with McKnight’s obvious interest in a kind of uncanny Surrealism.

Unlike earlier photographic projects such as Edward Steichen’s Family of Man (1955) or Robert Frank’s The Americans (1958) that attempted to democratize or taxonomize a population, McKnight is interested in a poetics of the imagination away from it. As opposed to a mere “dropping out” of society, the sparseness of his images suggests a tension between wanting to be a part of society and also knowing the importance of a temporary retreat. In McKnight’s world, a fallen tree evokes a foreskin or a sphincter. A shadow lingers over a torso and evokes the pursuit of a villain or one’s demons catching up with oneself. More crucially, his images portray a modern taboo or source of anxiety in society: intimacy.

Exhibition view of Mark McKnight: Hunger for the Absolute at Klaus von Nichtssagend. Courtesy of the artist and Klaus von Nichtssagend, New York.

The photographs are staged to facilitate the desire of the viewer onto the subjects. We become an unpictured third party to these relations, implicated in the act of McKnight’s voyeurism. There is a tension in McKnight’s photographs between the sharply registered chiaroscuro lines and the poetry of a corporeal performance that has been sequenced to seduce the viewer’s gaze. The ambiguity of these images is one of their greatest strengths, suggesting a dualism of mind-body as much as they refute it. Markers of subjectivity can be inserted—as in Laura Aguilar’s series Nature Self Portrait from 1996 or Judy Dater before her—but also exist ontologically, as per photography’s supposed invisible neutrality. McKnight’s experiments with a less defined sense of intimacy and playfulness speak volumes to a world increasingly preoccupied with drawing up rigid boundaries. His refusal to taxonomize is closer to what we have known to be “queer” in the structural sense. If Heaven is a Prison, as the title of McKnight’s accompanying monograph suggests, consider this a break from the routine.

Mark McKnight: Hunger for the Absolute is on view at Klaus von Nichtssagend Gallery in New York City until April 3 and at Park View/Paul Soto in Los Angeles until April 24.

Steven Warwick is an artist, writer, and musician living in Berlin. He was interviewed in BOMB in 2014 under his moniker Heatsick.