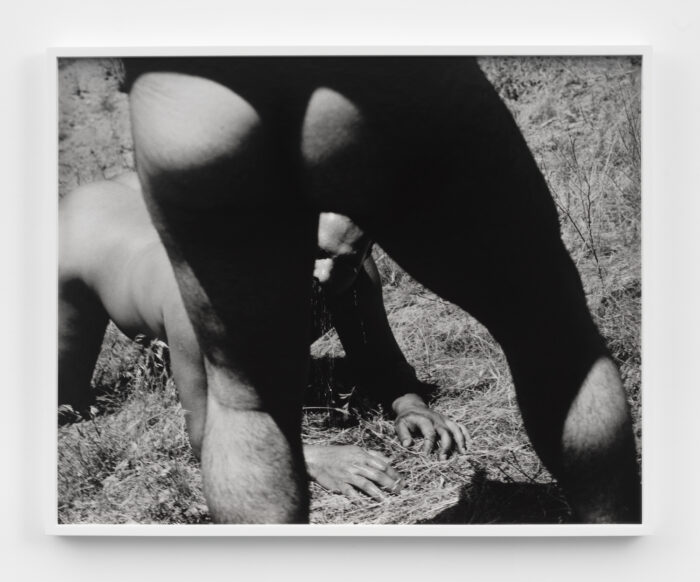

Mark McKnight, Untitled (Tree Void II), 2021. Gelatin silver print, 20 x 24 inches. Courtesy Klaus Von Nichtssagend Gallery, New York

The sun has never been higher. The clouds are stubborn, yet merciful. Light races toward the earth, hellbent on illumination. Shadows negate more than they conceal. The conditions are extreme and full of purpose. The landscape is a theater.

It could be no other way. Or at least, in Mark McKnight’s photographs made in the high desert in Southern California, that is how it seems. Drawn almost entirely from his remarkable monograph Heaven Is a Prison (2020), the photographs in Hunger for the Absolute dramatically expand, and forcefully concentrate, McKnight’s previous explorations of the landscape as a transmogrified space of sexual resonance and desire. With the company and collaboration of two friends, Nehemias de León and Christopher Barraza (named in the book but not in the exhibition), whose bodies structure the work both in their presence and their absence, McKnight has crafted a tender and hypnotic vision of romantic union through the joy of transgressive sex. Set against the luminous and austerely rendered desert landscape, his subjects piss and spit, dominate and submit—they eat ass and saunter through dappled shade.

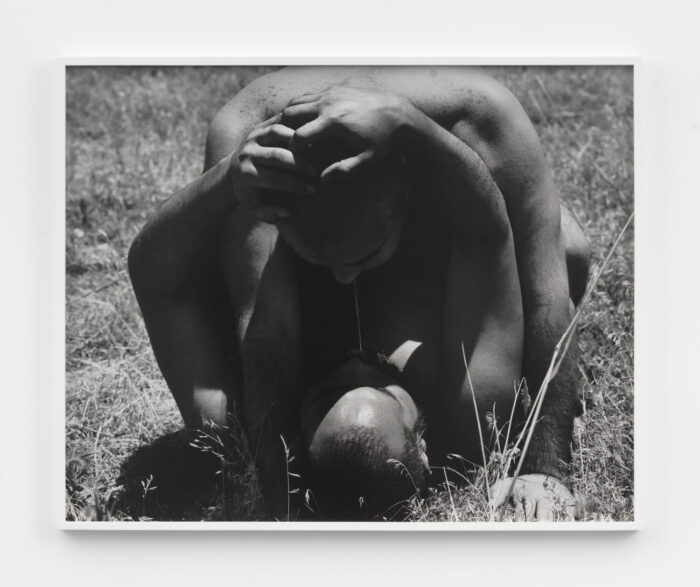

Mark McKnight, Beggar II, 2021. Gelatin silver print, 24 × 30 inches. Courtesy Klaus Von Nichtssagend Gallery, New York.

The first image we see, Untitled (Tree Void II) (all works 2021), is of a tree trunk split apart, its opening presented as an abyss, rendered in the shadowless black that McKnight pushes to its ultimate throughout the exhibition. The first room of photographs opens directly across from the ruptured trunk: a scene of sadomasochistic piss-play and spitting between the two men that is broken up into five parts across four walls.

In Beggar II, a man on hands and knees is framed through the legs of his partner, his face dripping with piss—there is more than a suggestion of eagerness, of willing submission, in his face. On the adjacent wall is an effective bit of curation between two images that work in relation to one another like units of a montage, both solidifying and complicating whatever situational deduction we may have already made. Crest shows a rhythmic dramatization of the landscape that is bereft of the human body, if only literally. McKnight renders a field of tall grass as though it were on the cusp of being consumed by an ever-expanding arc of shadow, its curvature seeming almost corporeal. Following this is an abrupt return to the body in Piss, in which we see a cropped shot of one man’s torso as he holds his penis, relieving himself into what we now know is not the wind.

Mark McKnight, Swap, 2021. Gelatin silver print, 40 x 50 inches. Courtesy Klaus Von Nichtssagend Gallery, New York.

Positioned on the wall opposite Beggar II is Swap, in which McKnight shows the instant of oral transfer: spit falling carefully and seamlessly from one mouth into another. The near-serenity of this moment is interrupted by an untitled diptych, which follows Swap and completes the room’s sequence. We are first shown the receiving mouth pried open with something that approaches aggression and, next, a focused detail of a cloudscape, with negative space printed black, cutting diagonally through two cloud banks. McKnight’s use of the sequence here is exemplary of how he layers inverse points of view, situating us as voyeur one moment and as a near-participant in the next.

McKnight uses this strategy regularly, toggling between points of view throughout the show. The cumulative effect, in the end, obviates what could be a far trickier dilemma: namely, how to insist on the centrality of explicit, often taboo, imagery, without also relegating other formal or conceptual concerns to the background. By placing ass-play and chained bondage alongside more conventionally delicate images of pleasure and embrace, and then using the landscape as a foil for it all, McKnight stretches the tapestry of the work far beyond any single-minded reading or emotional response. Such a tapestry, rich as it is in setting and circumstance alone, would nonetheless feel threadbare were it not for the expressiveness of McKnight’s long tonal range, which is made all the more dramatic by the way he is able to balance sharp contrasts within a single image. Working with a large-format four-by-five-inch camera, he has managed to make the lush desert landscape (a descriptive reality that is confusing in itself, and which ultimately intensifies the dream-like quality of the work) feel thin of air yet leaden in weight. For work so tangible in atmosphere, each print is an astonishingly precise affair: windswept fields and fluid cloudscapes have edges set like marble. The burly bodies of de León and Barraza are registered with such affection and depth of tone that, at times, they can seem a source of light all their own.

Mark McKnight, Wildflowers, 2021. Gelatin silver print 24 x 30 inches. Courtesy Klaus Von Nichtssagend Gallery, New York.

In the second and final room of photographs McKnight continues to press upon the relationship between intimacy and sexual domination, between power and tenderness. Two large works, Black Fly with Bodies, and Marriage (Sky, Horizon), are hung across from one another at opposite ends of the room. In Black Fly we see an obscured scene of intercourse between the two men, as one’s back fills the frame almost entirely. Instead of making the image explicit, McKnight allows for the emphasis of sensual details: the crossing of legs and overlapping of the lovers’ feet; supple flesh and taut muscles; the titular fly resting just-so above the small of the back. Across the way, in Marriage, is an image that one could imagine being far more confrontational in tone than McKnight allows it to be. In what is the only time he offers a glimpse of a horizon, the two men assume the roles of dominant and submissive, with one’s face pressed into the other’s ass, his wrists bound by chains the other controls. Their union is made complete.

For all the maximalism of these photographs, the wealth of detail and description, of staging and theatrics, there is a steady quietude to them as well, which in its way seems to underscore the euphoria of the work with patient introspection. Were the show in need of one, Wildflowers would be a fitting coda in this regard. No longer framed by each other’s bodies, nor within a landscape that feels as though it were cut from memory, both men walk through a tall patch of flowers, some burnt and withered, others flowering and potent. Shade ripples across their backs—a temporary respite. The tenderness of this moment, the sense that they are forgetting themselves together, if only briefly, is overwhelming.

Zach Ritter is a writer based in NYC. His writing has appeared in the Brooklyn Rail and Hyperallergic