In the male body and the physical world, an unexpected seduction.

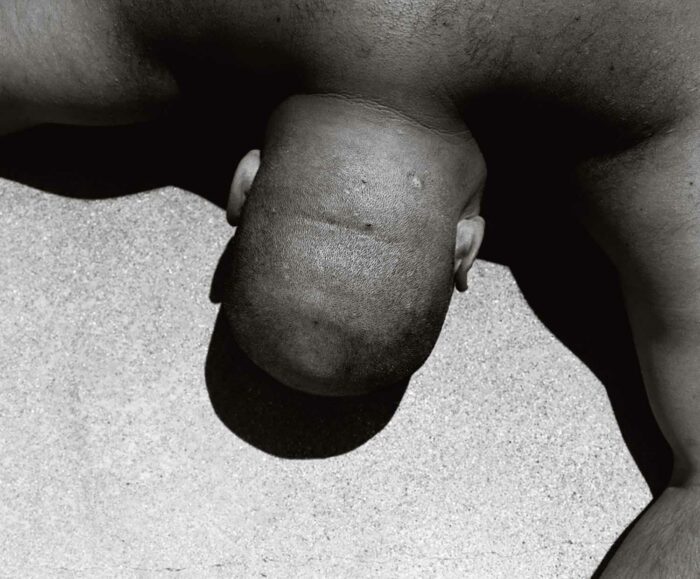

Mark McKnight, Ballerino, 2018

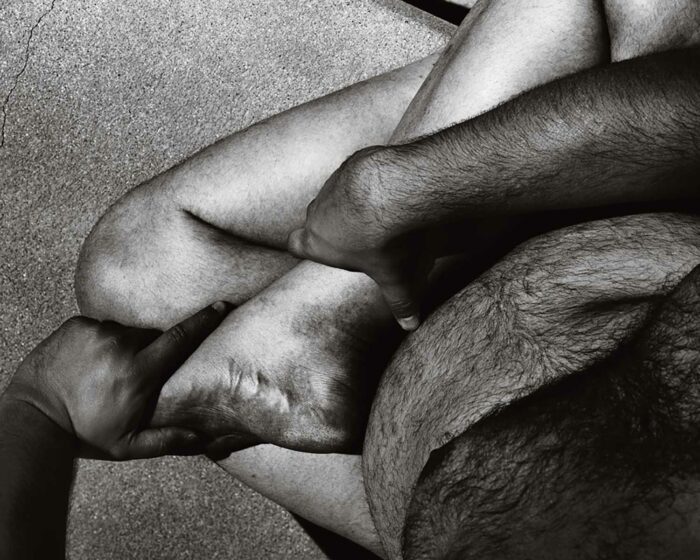

Mark McKnight, The Black Place, 2019

“I think we’re all constantly on the precipice of becoming another thing,” the photographer Mark McKnight says. A logic of transformation—of metaphor—animates his defiantly analog, large-format, black-and-white photographs. A torn bag of asphalt suggests the broken flesh of an animal; a blistered wall rhymes with a man’s mottled back; the play of light across tar reveals a cosmos. Bodies, landscapes, buildings are depicted in a way that makes them nearly interchangeable, equivalent to the eye and also, disquietingly, to our sympathy, so that traces of adhesive on a wall might be scars from a severed limb.

The extraordinary energy of McKnight’s images comes from a harnessing of contrary, even contradictory, forces. McKnight, who was born in Los Angeles, in 1984, chooses as his subjects men he knows and frequently is attracted to, members of his queer LA community. His photographs are redolent with intimacy, an extravagant tenderness. And yet, he photographs these men in ways that seem deliberately untender: starkly lit and in claustrophobic proximity, with every blemish displayed, frequently in postures, like that of Ballerino (2018), of literal abjection. It’s a treatment that suggests cruelty, though the pictures are never cruel; they are, it seems to me, the opposite of cruel. Almost always, the expected focus of tenderness and sympathetic attachment—the human face—is obscured, turned away from the camera or cropped out of the frame. McKnight challenges us to find grace in what might at first seem a graceless image, to linger on the elegance of the curves of a man’s flesh, to imagine, between body and shadow, a surreal pas de deux.

McKnight has resisted the idea that facelessness in his work stems from a desire for furtiveness or anonymity, insisting instead that it allows the men to be archetypal, figures of longing, time, vulnerability. But both anonymity and archetype are forms of abstraction, an abstraction that doesn’t cancel out the intimacy of the work but throws it somehow—as McKnight’s shadows, which he over-develops to an abyssal black, do for the surfaces that cast them—in starker relief. McKnight’s photographs of male bodies at once invite us close and ward us away; they are, in that way, mimetic of a particular experience of desire, a continually frustrating seduction.

“The pictures, like all things, are too complex to fully reconcile,” McKnight told me recently from his studio in LA. “And that’s something I appreciate about the pictures, not something that I run from.” McKnight’s willingness to abide with the irreconcilable gives these photographs their quality of inexhaustibility; it transforms them into objects of contemplation. Perhaps the contradiction in the work I can least account for, and that therefore feels most powerful to me, is the fact that although McKnight rejects so many of the usual sources of affect—facial expression, social context, identifiable narrative—his work is drenched in affect, supersaturated with emotion in a way that feels almost operatic, exuberantly queer.

Take, for example, Bodyfold (2019). The subject at first seems clear: a man sitting in the sunlight, his right leg folded over his left. But the details are indeterminate: Is he sitting directly on the concrete, or perched somehow above it? Is that black triangle at the bottom of the image a shadow or a chair? He’s naked, and the camera gazes into his lap—it could nearly be, but isn’t quite, the subject’s own gaze—but what we might have thought would be the object of desire is hidden from us, the leg pulled tight against the body to hide his cock from view. Or maybe nothing is being hidden; maybe the man is indifferent to us, maybe the posture is for his own comfort. There’s a suggestion of self-sufficiency in the way he holds himself, his ankle gripped by his right hand, his toes by his left, the thumb stretched along his sole. The photograph’s erotic intimacy lies in that touch, I think, its suggestion of pleasure given by and taken in himself.

Mark McKnight, Bodyfold, 2019

Bodyfold moves me because of its subject, a type of body—hairy, thick, nonwhite—often excluded from the canons of beauty; but it moves me more because of the intricacy of its composition, the complexity of pattern that gives the photograph its compelling density. How curious that so much of the photograph’s affect lies in what might seem to be affectless geometry—but then, that geometry is the measure of the craftsman’s care, the claim to value we always make when we transform something into art.

It took hours for me to become conscious of Bodyfold’s most heartbreaking detail: the hairline crack in the concrete in the upper-left-hand corner of the image. It’s a little death’s head, I think, a touch of entropy, time’s signature: an organic curve that echoes the man’s body and reminds us of the transience that—voracious, indiscriminate—claims everything we lavish our care upon, concrete as surely as flesh.