The “body as a landscape” is an infinitely renewable cliché in art, one that draws its power from the collision between shifting human passions and nature’s steadfast indifference. At its best, it inspires work that collapses the distance between our interior sensory world and the environment around us, either imbuing everything with consciousness or recognizing our own as a particularly freaky extension of nature.

In a recent discussion with Los Angeles–based photographer Mark McKnight held within his exhibition at Aperture (which had awarded him its 2019 Portfolio Prize), poet and novelist Garth Greenwell touched on what he sees as a great difference in the development of their respective art forms. At the genesis of American poetry was Walt Whitman, a figure who sowed the foundations of the canon with a queer approach to nature and spirituality. Conversely, a pioneer in American photography was Minor White, who depicted American landscapes and people in an expressive manner but sought to suppress his sexuality. As critic and editor Ingrid Sischy once wrote, White “obeyed the conventions of his time, and one of them was that if you were unfortunate enough to love your own sex—which he did—you controlled that information, and certainly didn’t advertise it in your work.”

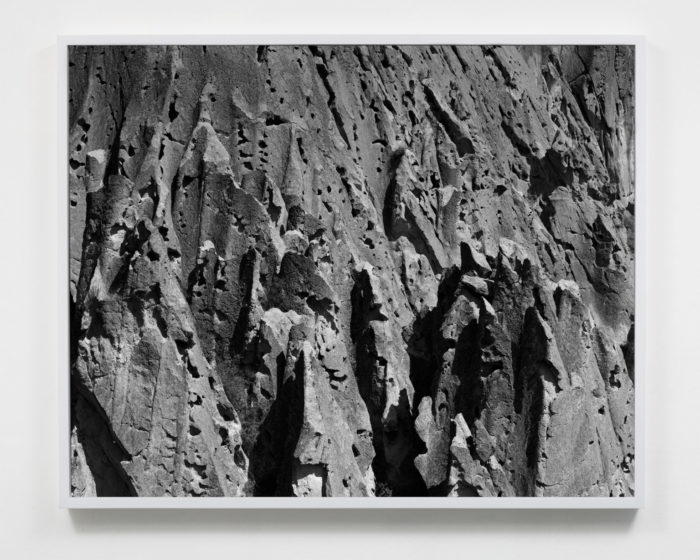

The photographs in McKnight’s Aperture exhibition and in a second show at Klaus von Nichtssagend gave beautiful shape to the sort of queerness that White tried to contain, and to the aesthetic he might have developed had he been in full possession of his self. Portraying the body as formalist landscape and psychological landscape at once, McKnight marries two strains of image-making that on their surface seem like contradictions. If queer formalism in photography is most closely associated with Robert Mapplethorpe’s ultra-kinky, mostly hairless, vaguely fascistic musclemen, McKnight carves his own path by capturing softer-bodied hirsute subjects whose folded flesh, wisps of fur, and pockmarked bellies become abstract landscapes that recall those of masters like White.

McKnight’s work is as concerned with negation as it is with affirmation, his images not only exposing their subjects but also anonymizing them. His sleight of hand as a photographer is to confront viewers with the fact of his models’ abjection while presenting it in the space of perfectly composed and gorgeously shot pictures. The twisted, fragmented flesh on display in His Birth (or Black Egg), 2019, and Bodyfold(2018)—at Klaus and Aperture, respectively—has the gnarly corporeality of sculptures by Robert Gober, though it is given the classic gloss of the gelatin silver process.

One of McKnight’s greatest strengths is in naturalizing the artificial and aestheticizing the natural, as seen in a number of works at Aperture. Destructive Distillation (Tar Cosmos), 2018, is a portal to the stars found in a puddle of sludge, while the inflatable ball in Spinning Away (2018), with its amorphous red spot, suggests both Jupiter and a very puffy nipple. In Eros (and Erosion), 2018, the camera looms over a backside speckled with psoriasis scars, the bruised flesh finding a sweet analogue with the warped desert earth it rests upon. In its formal beauty, ambient horniness, and casual psychedelia, McKnight’s vision of rugged American landscapes is surpassed only by Georgia O’Keeffe’s.

McKnight is not simply a romantic. The palpable warmth he feels for his subjects is paired with an unrelenting starkness of vision. Moral ambiguity lurks in the bleak terrain of pieces like The Black Place and the jagged cliffside of Violence (both 2019 and at Klaus). When an audience member at the Aperture discussion asked McKnight whom he considered to be the equivalent to Whitman in photography, he cited Frederick Sommer rather than White. For his classicism and refined touch, McKnight is a true disciple of Sommer’s gorgeously delirious vision of the desert, merging the physical and psychic to depict the truth of a very modern nature.