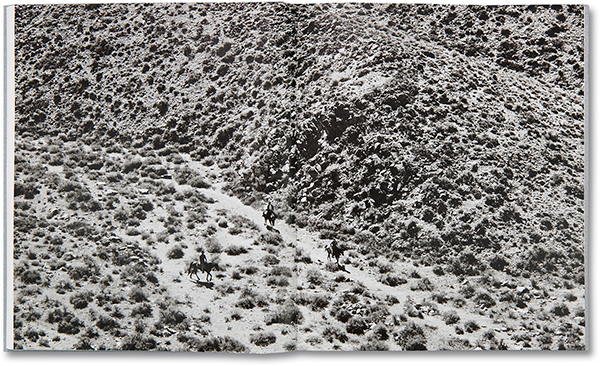

Sam Contis, Across the Valley (from Gilbert Pass), 2014

Courtesy the artist and Klaus von Nichtssagend Gallery, New York

People who come to California from somewhere else are often unprepared for this place. Wallace Stegner wrote of California that “perceptions trained in another climate and another landscape have to be modified” here, and we discover the need “to learn all over again how to see.” The photographer Sam Contis, originally from the East Coast, was compelled by the idea of recalibrating her vision of the American West through the lens of the Golden State—a dreamland defined by desert, drought, Hollywood films, heat, cowboys, freedom, reinvention, and open space.

Sam Contis, Arbor, 2014

Courtesy the artist and Klaus von Nichtssagend Gallery, New York

On a road trip in 2013, Contis found her way to Deep Springs, the name of both the valley and a remote liberal arts college nestled between the Inyo and White Mountains in the far-eastern part of the state. She recognized immediately how that specific landscape could shift her conception of the West and its mythology. Returning periodically over the course of four years, and collaborating with students, she created the series that became her first photobook, Deep Springs (2017), from a place that itself has perpetuated its own mythical status.

Sam Contis, Eggs, 2015

Courtesy the artist and Klaus von Nichtssagend Gallery, New York

Deep Springs College was founded in 1917 by L. L. Nunn. An electricity tycoon, Nunn was also a philanthropist who fashioned himself a “builder of men” by way of a college that would encourage students to develop “ideals of freedoms and lives of service.” For the last century, only the brightest young men have been admitted to study at Deep Springs. Coursework is balanced by manual labor: students maintain the ranch and farm on which the college is located, and they more or less govern themselves during their two years in residence. Into this masculine environment Contis inserted herself and established a temporary home while she explored the valley. The notion of a rugged, male-dominated western landscape loomed large and became her subject.

Sam Contis, Hold Down, 2014

Courtesy the artist and Klaus von Nichtssagend Gallery, New York

Students from Deep Springs feature prominently, albeit anonymously. Contis observed her young subjects as they wrestled, slept, rode horses, and matured. She was also an active participant who quietly entered a terrain marked by invasion, and interrogated the common mythologies of the West by offering a more personal, private vision. Acknowledging the long legacy of photographers inspired by California’s landscapes—William Henry Jackson, Timothy O’Sullivan, and Carleton Watkins—Contis presents the West as a place of exploration that is more intimate than distanced. Like the students of Deep Springs, Contis looks to the West—both the land and the people in it—as a source for defining one’s identity and sense of purpose.

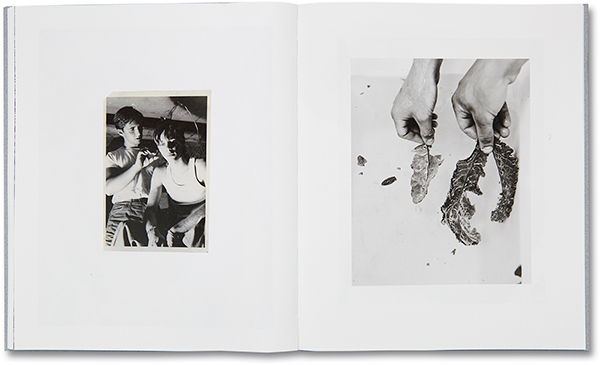

Spread from Deep Springs (London: MACK, 2017)

Courtesy the artist and MACK

In reverence to her artistic forebears, Contis began the project by utilizing a 4-by-5-inch plate camera. One reason she refers to the project as a collaboration is her choice of equipment: occasionally she would ask the young men to repeat a motion or gesture, simply because she couldn’t reload film fast enough. But she also relished the opportunity to update the prevailing nineteenth-century photographic portrayal of the isolated, stationary, sepia-toned western landscape, using digital technology and color film to inject motion and life.

Spread from Deep Springs (London: MACK, 2017)

Courtesy the artist and MACK

Deep Springs reveals a preoccupation with skin and flesh, beginning with the cover of the book: a photograph depicting the lithe curve of a muscular, indented back is printed directly on the grey paper that envelops the cover cardstock. Skin pressed up against skin. (And, in perhaps a subtle nod to the physical terrain of Deep Springs, the cover itself comes to resemble granite, which abounds in the valley.) Opening the book reveals the soft pink end paper; lifting this outer layer, we enter the flesh of the narrative.

Sam Contis, Close Cut, 2013

Courtesy the artist and Klaus von Nichtssagend Gallery, New York

Contis often focuses on the bodies of her subjects—virile, sinuous, sometimes indeterminate—and shows the strength and softness that these young men embody simultaneously. Walt Whitman’s poem I Sing the Body Electric resonates here, both for the beauty of human forms registered in the images and the allusion to Nunn’s profession, which serviced the creation of the college. In Deep Springs, tender close-ups reveal the gentle crook of an elbow, the grooves in a neck, the lines of a hand. They celebrate Whitman’s lyric: “To see him pass conveys as much as the best poem, perhaps more, / You linger to see his back, and the back of his neck and shoulder-side,” forming a visual poem of their own. The careful sequencing of images—with a selection that incorporates pictures made by some of the first students at Deep Springs, which Contis unearthed in the college library—reverberate between past and present. Photographs occasionally cross the gutter like an enjambment, or step across the pages like notes on sheet music, resembling the kind of triadic rhythm found in the work of William Carlos Williams. To invoke Whitman again, here is a book that encapsulates the phrase “your very flesh shall be a great poem.”

Sam Contis, High Noon, 2014

Courtesy the artist and Klaus von Nichtssagend Gallery, New York

Deep Springs allowed Contis to defy tradition as much as honor it. The project provided the space, and the freedom, as she says, to “let go of the idea that work needs to be made in one format.” She could resist or embrace speed. She could capture the infinite horizon, or study textures as delicate as dust and tallow. In other words, just as fault lines spread out like subterranean highways below the sun-bleached terrain of California, Contis’s notions about photography began to fissure and crack open. Perhaps for Contis, who now calls California her home, there may be some truth, as Stegner once wrote, that “the West is less a place than a process.”

Amanda Maddox is assistant curator in the Department of Photographs at the J. Paul Getty Museum.

Deep Springs was published by MACK in 2017. Sam Contis: Deep Springs is on view at Klaus von Nichtssagend Gallery, New York, through June 18, 2017, and Sam Contis / MATRIX 266 is on view at the University of California, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive until August 27, 2017.