At first glance, the central figures who populate the eight paintings that make up Tamara Gonzales’s third one-person exhibition at this gallery seem to conjure memories of the Neo-Primitivist wing of the 1980s Expressionist painting revival, when such artists as Keith Haring and A.R. Penck freely brought angst and whimsy to their re-working of figuration derived from cave paintings and tribal art. Despite their quite different starting points, by today’s guidelines both Penck and Haring could be labeled as cultural appropriationists, since their wholesale sampling of non-Western motifs was not only unacknowledged as such, but served, somewhat perversely, to underscore both artists’ claims of stylistic innovation.

At first glance, the central figures who populate the eight paintings that make up Tamara Gonzales’s third one-person exhibition at this gallery seem to conjure memories of the Neo-Primitivist wing of the 1980s Expressionist painting revival, when such artists as Keith Haring and A.R. Penck freely brought angst and whimsy to their re-working of figuration derived from cave paintings and tribal art. Despite their quite different starting points, by today’s guidelines both Penck and Haring could be labeled as cultural appropriationists, since their wholesale sampling of non-Western motifs was not only unacknowledged as such, but served, somewhat perversely, to underscore both artists’ claims of stylistic innovation.

In Gonzales’s case, the question of attribution is placed front and center, beginning with the title of her exhibition, Bo Yancon, which is the nickname given to her by the indigenous Shipibo people of Peru. In recent years, Gonzales has made numerous trips to Peru, and her time spent living with and learning from the Shipibo has served as a proverbial deep dive into a particular non-Western system of belief and custom that has sustained itself over centuries of oppression alternating with indifference. Back in her Brooklyn studio, Gonzales’s efforts to transform both the emotional raw material of her research, as well as actual patterns and motifs found in Shipibo textiles, result in compositions that seek to retain the freshness and urgency of her experiences, while opening up a space in contemporary artistic practice for a non-exploitative relationship to pre-Colombian cultures.

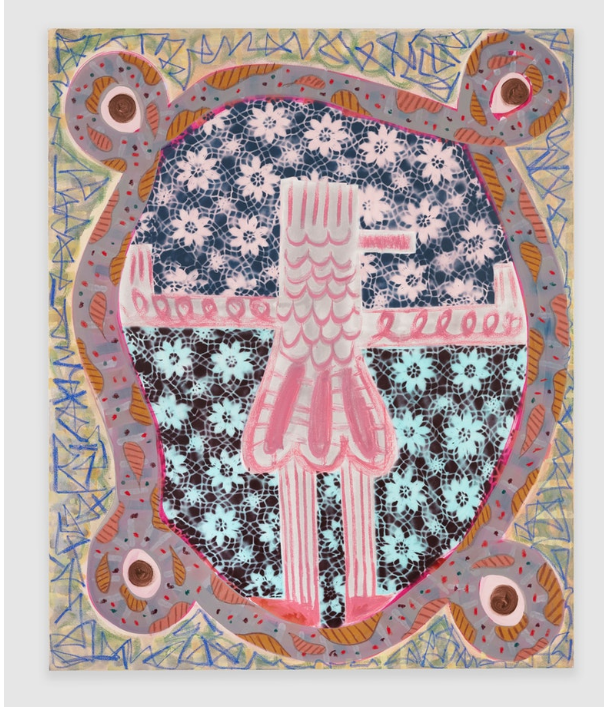

Gonzales developed the paintings in her previous exhibitions using a lot of spray paint and lace stencils, which lent a rugged, woodblock-print texture to the overall design, but at the occasional cost of diluting the vigorous tactility inherent to her own brushwork. By contrast, these new paintings de-emphasize everything except the paintbrush, with the result that they have a crisp all-over feel, while highlighting her considerable gifts as a colorist. In Videira de Cobra Para as Estrelas [Snake Vine to the Stars] (2018), a single gray and pink figure in ceremonial dress, set against a field of blue and pink flowers, seems to push at the inner boundaries of a thick rope-like enclosure rendered in gun-metal and butterscotch. By permitting a great deal of background light to show through her semi-translucent paints, Gonzales achieves an airy feeling of spontaneous levity that belies the apparent solemnity of the depicted action.

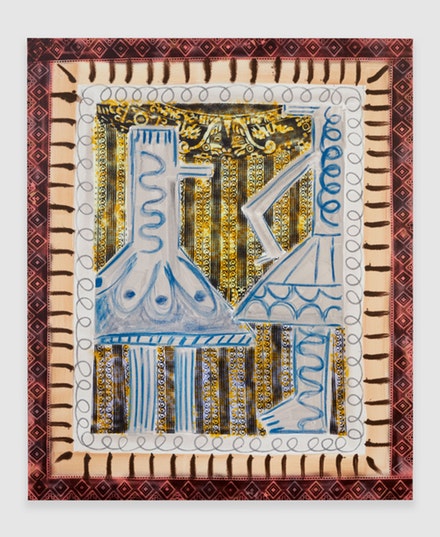

Gonzales’s technique of visually reinforcing each picture’s outer edges by incorporating repeated interior frame-like outlines helps reinforce their sequential appearance as potential episodes within a larger narrative. Thanks to their generalized, “primitive” appearance as rendered figures, each of the central personages might easily be understood as being the same figure, perhaps at different stages of life. The autobiographical reference in Pausa Con Mi Abuela [Pause with My Grandmother] (2018) even suggests a further reading: foundational memories revisited in the form of visions derived in ritualistic meditations, like the ayahuasca ceremonies that have recently increased in popularity for visitors, who often spend time with indigenous Andean communities in order to attain spiritual insight and awareness through the controlled use of natural hallucinogens, typically with a native guide to accompany the experience. In the painting, the smaller of two figures seems to have stopped in her tracks, while the taller figure stands aside her, arms akimbo, the upper part of her head cropped by an inner frame. The grandmother doesn’t touch the child or directly interact with her in any obvious way, other than to stand by observantly and give her full attention to the child’s evident moment of self-awareness.

An unexpected outcome of the broader cultural discussions that have ignited around us in recent years is the realization that the art world not only has a responsibility to take full participation in such discussions, but it has sometimes, with the best intentions in the world, doubled as the scene of the crime. This is particularly fraught when it comes to cultural appropriation, as evidenced by the collective shudder felt a couple of years ago, when such admired artists as Sam Durant and Dana Schutz found themselves at the receiving end of accusations that no self-identified progressive citizen (much less an artist) would ever want laid on them. As a result of these controversies, there does seem to be an increasing consensus that the wholesale appropriation, by artists with tangible influence and privilege, of painful and/or sensitive historical realities endured by certain minority cultures that have historically enjoyed far less influence and privilege, simply isn’t sustainable. An alternative approach that Gonzales’s new work points to is that if we wish to share the wisdom and beauty of the planet’s non-industrialized societies with our cosmopolitan peers, the provenance and lineage of such borrowings must be acknowledged, attributed and handled with unforced reverence.

An unexpected outcome of the broader cultural discussions that have ignited around us in recent years is the realization that the art world not only has a responsibility to take full participation in such discussions, but it has sometimes, with the best intentions in the world, doubled as the scene of the crime. This is particularly fraught when it comes to cultural appropriation, as evidenced by the collective shudder felt a couple of years ago, when such admired artists as Sam Durant and Dana Schutz found themselves at the receiving end of accusations that no self-identified progressive citizen (much less an artist) would ever want laid on them. As a result of these controversies, there does seem to be an increasing consensus that the wholesale appropriation, by artists with tangible influence and privilege, of painful and/or sensitive historical realities endured by certain minority cultures that have historically enjoyed far less influence and privilege, simply isn’t sustainable. An alternative approach that Gonzales’s new work points to is that if we wish to share the wisdom and beauty of the planet’s non-industrialized societies with our cosmopolitan peers, the provenance and lineage of such borrowings must be acknowledged, attributed and handled with unforced reverence.