Benjamin Butler was born in Westmoreland, Kansas. He received a BFA from Emporia State University, and an MFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. His work is represented by Klaus von Nichtssagend Gallery (New York), Galerie Martin Janda (Vienna), and Tomio Koyama Gallery (Tokyo). His show Another Tree, Another Forest was at Martin Janda this spring.

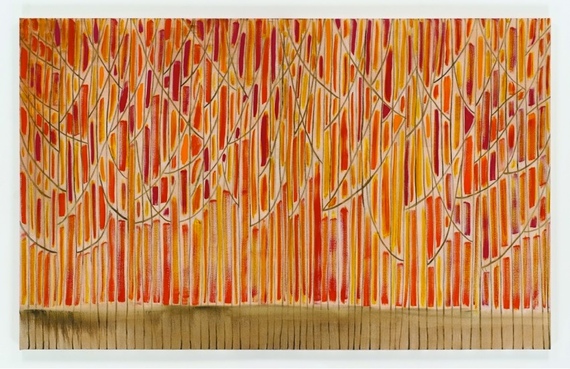

Autumn Forest (Sixty-Three Trees), 2012, 60 x 96″, oil on canvas, courtesy the artist and Galerie Martin Janda, Vienna

RH: I’ve known your work since your very first show at Team Gallery in 2002. Your subject matter has stayed remarkably consistent for over ten years (mountains and trees), but your work has shifted considerably. Can you talk about invention and growth in your paintings?

BB: The landscape motifs were, in the beginning, a way to make abstract paintings that were modest and accessible to a wide audience. I thought of the mountain paintings, in particular, as ready-made compositions or spaces that I could very freely paint inside of. Early on, I was using source materials, like calendars, greeting cards, thrift store paintings, and sometimes ‘fine art’. When I began to focus on painting trees and forests, source materials became less necessary, and now (since at least 2006) are completely unnecessary. I’ve always thought that ‘painting’ was the true subject matter, though, and that the trees were something to look through to see the ‘painting’. However, there is something important about the self-imposed repetition that occurs in my work. When you paint what is basically the same thing over and over, you have to find other ways to keep yourself interested.

When you say ‘painting’ is the subject, what does that mean for you? Another generation of painters might be talking solely about materiality, texture, color. You are, in a way, but ‘painting’ isn’t so simple.

To some extent, I do mean ‘the act of painting’, which is, of course, a loaded subject. One could make the argument that every brushstroke carries the weight of every brushstroke that came before it. Basically, there’s a historical dialogue that painters can reference, participate in, and present to viewers. Ten years ago, I took part in a panel discussion about Contemporary Painting, in Salzburg, Austria. It was fairly early in the morning, and the first question for our panel was “What is Painting?”. I remember giving a somewhat meandering answer, fueled by 3 espressos. It bothered me, for a while afterwards, that I didn’t really have a clear answer. Perhaps a month or two later, I had a delayed moment of clarity, and a proper answer to the question. ‘Painting is an attempt to define what painting is, through the act of painting. Every painter is defining what painting means for him or herself.’ That’s still the best answer I can give.

Your early tree paintings recall the ‘transitional’ paintings of Mondrian. Modern Art historians will tell you that he later progressed to a purer abstraction. But you’ve held that space since you started showing…

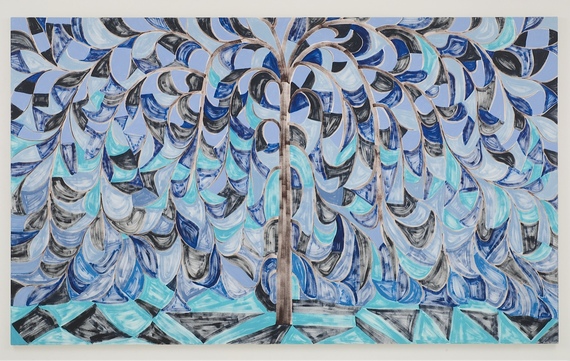

I used to be very interested in combining dissimilar art historical reference points, into singular paintings. It was definitely important for me to use a simple/modern subject matter, the landscape, as a context for what was essentially a post-modern strategy. The landscape format made what could have been a heavy-handed idea more bearable to me. Mondrian was a part of this historical discussion that was happening in my paintings. The singular tree framework/motif functioned like a time machine for me. I often thought to myself, “Imagine if Mondrian had never stopped painting trees, and was then influenced by the many abstract painting languages which came later (that Mondrian, himself, had actually influenced)”. This non-linear, and slightly absurdist idea, was incredibly helpful in pushing my project forward. The often-discussed idea of abstraction and figuration, and the blurring of the two, I’ve always thought, is a rather natural and unavoidable effect of putting paint on canvas. However, it does, usually, make a painting more compelling to look at, for a longer amount of time.

It’s interesting to think about your work in a tradition of sincere romantic painting, both landscape and abstraction. At the same time, it relates to post-pop strategies of mechanical production and appropriation of popular taste and kitsch.

The image of a tree can be found in most places these days, it’s universally recognized to the point of being cliché or worn out. Painting has a similar reputation, and it’s important, I think, to acknowledge that. It’s a little bit like karaoke. We’re mostly singing pre-existing pop songs and love ballads. There can still be magical ‘karaoke’ moments though. A technically bad singer can be more interesting than someone who is hitting the right notes, and occasionally there are transcendent performances. The same thing happens in painting. A trip to a flea market or a thrift store painting can sometimes be more interesting than a lot of what you’d find at an art gallery. This dichotomy between the romantic and kitsch, and also ‘high’ and ‘low’ art, was definitely important to the genesis of my work. I was approaching it from a sincere direction though. My grandmother asked me to paint her a landscape when I had a chance. I thought a lot about her request as my work began to take shape. It was an opportunity for me to filter what I had learned in graduate school through a simple and universal subject matter.

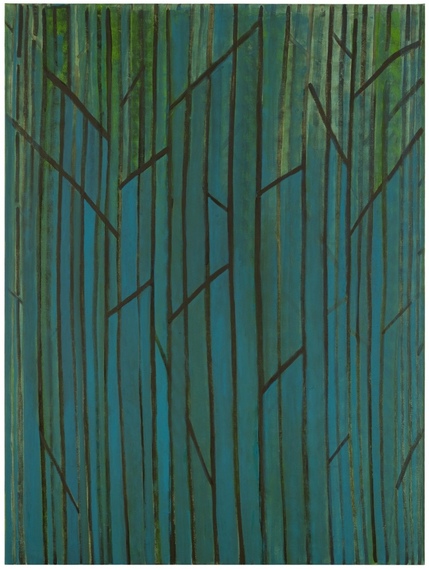

Untitled Forest, 2015, 94.48 x 70.87″, oil on linen, courtesy the artist and Galerie Martin Janda, Vienna

Are there systems you develop for color? Do you think about light or time of day? Or is the focus more on the internal logic of the painting and design?

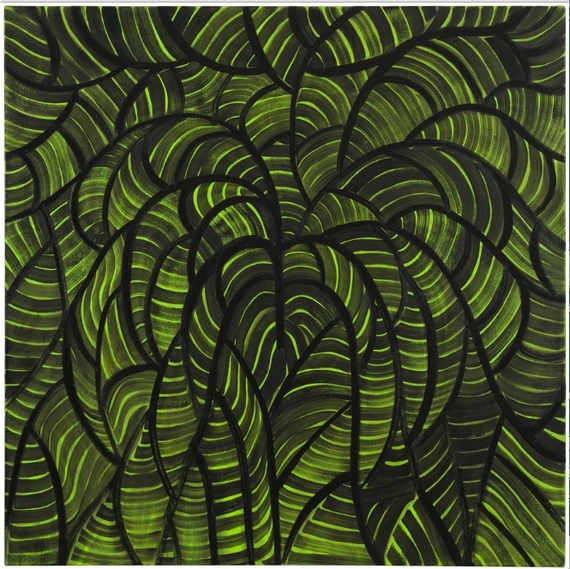

My color decisions happen for different reasons. Sometimes they have to do with how one painting will relate to another in an exhibition, or possibly the tone or concept of an entire exhibition. Because I’m essentially behaving like a landscape painter, I sometimes use pre-existing, common sense, color choices that, for instance, might reference the 4 seasons, darkness, or nature itself. I recently made a painting show called “Green Forest” which was an all-green show, because that’s what color a forest is.

Untitled Tree (Blue, Turquoise, Black), 2007, 72 x 120″, oil on canvas, courtesy the artist and Klaus von Nichtssagend Gallery, NY

Do early color decisions dictate the painting, or vice versa? They are done with a kind of brevity that makes me think you make a lot of decisions before putting down paint.

I generally have some plan for a painting, but it’s usually connected to what happened with the paintings that came before, and it’s not a perfect plan, most of the time. This usually assures that there’s still some invention happening from one painting to the next, and failure is definitely an important part of the process. That said, I think I prefer to have a painting appear to be efficient and effortless, even if it’s not.

Dark Tree (Green), 2015, 47.24 x 47.24″, oil on linen, courtesy the artist and Klaus von Nichtssagend Gallery

In some ways, your paintings seem to be so much about drawing. There is a focus on design and structure. And when you make marks, the delivery is so direct, and somehow linear. Do you think about that at all? Do you still draw often?

The past year, I’ve been drawing more often, with colored pencils and watercolor. In the past I’ve mostly made drawings that were specific to exhibitions. My drawings aren’t plans for paintings, though, and actually, I don’t really think about them as being very different. Sometimes I draw on canvas, and I also paint on paper. I have also purposely made paintings that function more like drawings. I’m definitely interested in mark-making, but I’m probably more interested in stylistic ideas and how they relate to one another. Drawing and painting are both ways to make a mark on a surface. Mark making, like writing, is a way of recording and discussing language and history. As a painter, that’s what I’m trying to do, but it’s, of course, a fairly abstract conversation. I try to make this conversation as direct as possible, with the idea that someone else might be able to pick up on what I’m trying to say. For this reason, a lot of the processes that go into my paintings are clearly visible. You can generally see the way my paint gets applied.

There is a very specific amount of restraint in the paintings. The coolness is central to your work. How do you decide how much to give or withhold?

This is difficult to answer, because it’s more interesting for me if my paintings don’t have the same conclusion. This is an import part of what shapes my work. I suppose the best paintings feel like questions to me, questions that can never be fully answered. I’ve studied painting fairly closely, so if I’m able to make something that feels like a giant question mark staring back at me, then that’s something that I want people to take a look at. It’s when the questions get answered, that it’s time to move on.

It seems that how to deal with the inevitability of ‘influence’ and historical precedent is a generational issue. It was a central to both the curating and criticism of that recent MOMA show. Purity was always a ruse, but the internet has made it absurd. Do you think about how you process influences? Who do you find yourself looking at most often?

In graduate school, I worked in the Flaxman Art Library. I had great moments of discovering new artists and painters while shelving returned books. I’d like to think that looking at art in books is a step closer to the real thing, because it’s a more tactile experience, but now I use the internet similarly. Gerhard Richter’s writings became important to me then, and also Peter Halley’s Collected Essays. Basically every facet of mid-century abstraction has peaked my interest at one point or another, with too many names to mention. These days I’m most interested in Post-Minimal and Conceptual Painters like Robert Ryman, Agnes Martin, On Kawara, Ad Reinhardt, and Raoul de Keyser. I also really like the accessible and pyschedelic qualities of Yayoi Kusama and Victor Vasarely. Milton Avery’s impact on Color Field painting through his friendship with Mark Rothko often comes to mind, as well as the psychological landscapes of Charles Burchfield, Albert Pinkham Ryder, and Ralph Blakelock. I saw the Giorgio Morandi show at the Met in 2008, and I can’t stop thinking about something I read in the wall text. Apparently he was a rather tall man living for a long time in a small Bologna apartment with his three sisters. It’s impossible, now, not to think about his paintings as claustrophobic family portraits.

You recently moved from New York to Vienna. How is it working there as a painter? Has the environment changed anything in your work?

When I first moved here, I calculated that in the 13 years I lived in New York City, I saw over 5000 exhibitions, and that’s a conservative estimate. It was definitely important for me to see a lot of exhibitions in my 20’s and 30’s, in order to define my work, ideas, and taste. Living in Vienna, for 3 years now, I’ve been able to focus much more on my own work. The timing felt right for a change of pace and I think it’s had a good impact on my painting. I also recently became a father. When our son was first born, life became very simple (for the first few months). I was making paintings and changing diapers, and there were a surprising number of similarities between the two! This was a beautifully balanced time at home and in the studio.