Pamela Jorden:

Making Reflector

Pamela Jorden employs to dramatic effect the many elements that make up a painting. Raw and treated linens are carefully cut and folded to stretch tightly across contoured stretchers. Oil and acrylic paints combine in layers of color, texture and transparency. The wall itself is considered in the making of the work, providing reflections and a play between positive and negative space. “Reflector,” Jorden’s current show at Klaus von Nichtssagend Gallery is her most ambitious show to date; each work combines a pair of adjacent shapes constructed at full body scale. Paint is poured, allowing the color to pool, stream, drip, or fracture in prismatic fields that evoke the vistas and landscape of Southern California surrounding the artist’s studio. The physicality of these works is assertive, while Jorden’s care to detail draws one into the light and motion that are her focus.

Shadow Painting, 2020

acrylic and oil on linen

72 × 25 inches (182.88 × 63.50 cm)

Heliotrope, 2020

acrylic and oil on linen

72 × 72 inches (182.88 × 182.88 cm)

Spine, 2020

acrylic and oil on linen

72 × 42 inches (182.88 × 106.68 cm)

I pour paint across surfaces with directed and uncertain results. My paintings are improvisations, exploring qualities of reflection, energy, movement, magnetism, and light. Color is intense yet fleeting, depending on how light or perspective alters the visual experience of a painting.

Rather than functioning as windows into a representational or pictorial space, the paintings assert their object-ness and materiality. The color fades and the bleeds suggest atmospheres, ebbs and flows, celestial bodies, or waterways and light, but the space is often topsy-turvy, with multiple horizons, or bending, warping space.

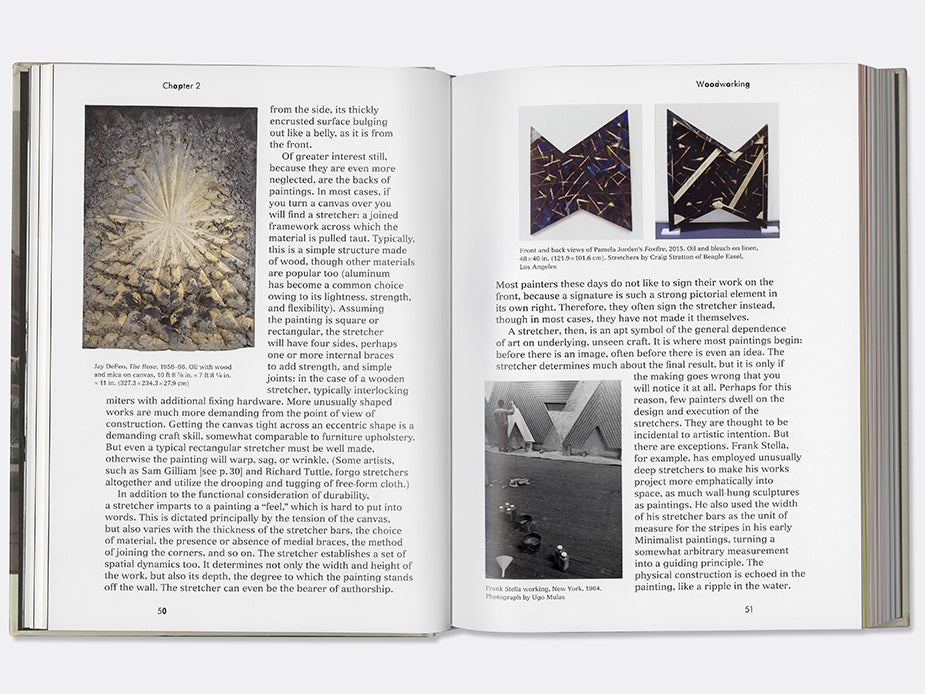

Artists and Their Materials from the Studio to Crowdsourcing.

Since the mid-twentieth century, it has become customary not to frame paintings…so you can see the sides of most modern canvases. Some artists finish this exposed surface cleanly…Others are more casual, allowing drips, fingerprints, and stains to remain visible.

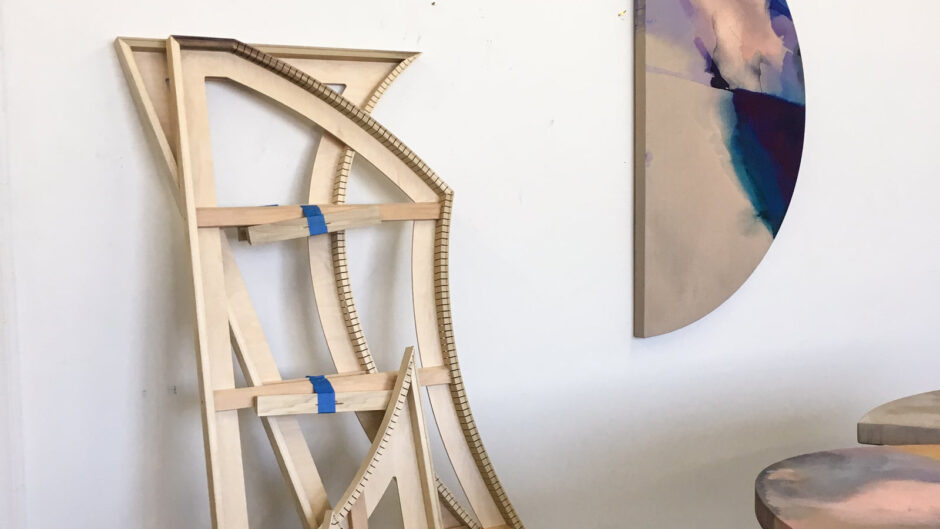

Of greater interest still…are the backs of paintings. More unusually shaped works are much more demanding from the point of view of construction. Getting the canvas tight across an eccentric shape is a demanding craft skill, somewhat comparable to furniture upholstery.

A stretcher…is an apt symbol of the general dependence of art on underlying, unseen craft. It is where most paintings begin, before there is an image, often before there is even an idea.

— Glenn Adamson, Julia Bryan-Wilson

“In the past your abstract fields were cropped into a rectangle or a square, and so seemed like the “picture” might continue indefinitely. . . . [In recent work] patterns bump up against the edges: round, ocular paintings vibrate, the marks push against the boundary; if the marks on the canvases were circular they might continue their spin”

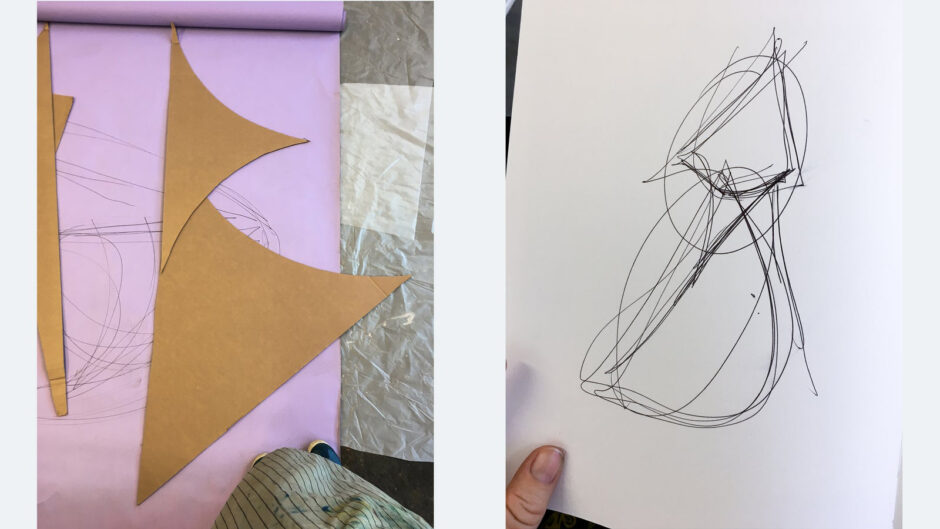

Views From Studio and Home

photography and edit by Pamela Jorden & John Pearson

Pamela Jorden monograph, 2015

contributors: Sarah Lehrer-Graiwer, Alice Könitz, and Kaveri Nair

[Jorden’s] paintings are both passive and highly sensitive to psychic contact, like a mood ring, while also being mood altering. . . . The acoustic sun, moon, and foghorns Arthur Dove painted resonate here in the art historical distance. Glowing-light atmospherics, like a stoplight in the fog or a spectral prism: halo, softness, astral fuzz, haze, and shimmer. The metallic glitter and faint iridescence in some paints she uses (the silvers, with mica flakes) are precisely unphotographable—even as, on a certain level, hers are paintings about vision in (or defiantly in spite of) this age of cameras and roboticized lenses.

—Sarah Lehrer-Graiwer, Adjusted Foci: Pamela Jorden Starting Points

Purchase Book