After a tumultuous restructuring last year — when MOCAD’s former executive director Elysia Borowy-Reader was fired for no cause following allegations of racism and workplace toxicity — the museum reopened with renewed intentions of centering local artists and artist of color under the astute guidance of senior curator Jova Lynne. Following the museum’s “Dual Vision” exhibit which featured 40 Detroit-based artists, MOCAD introduces its summer exhibitions which explore themes of identity, community, and racial equity.

mong these collections are Well Wishes by Hamtramck-based artist Amna Asghar and Filling in the Cracks by St. Louis artist Damon Davis. Both artists pull from their repertoire of personal experiences to create imagery that represents them at their most vulnerable while offering the viewer a lens through which to contextualize their own identities.

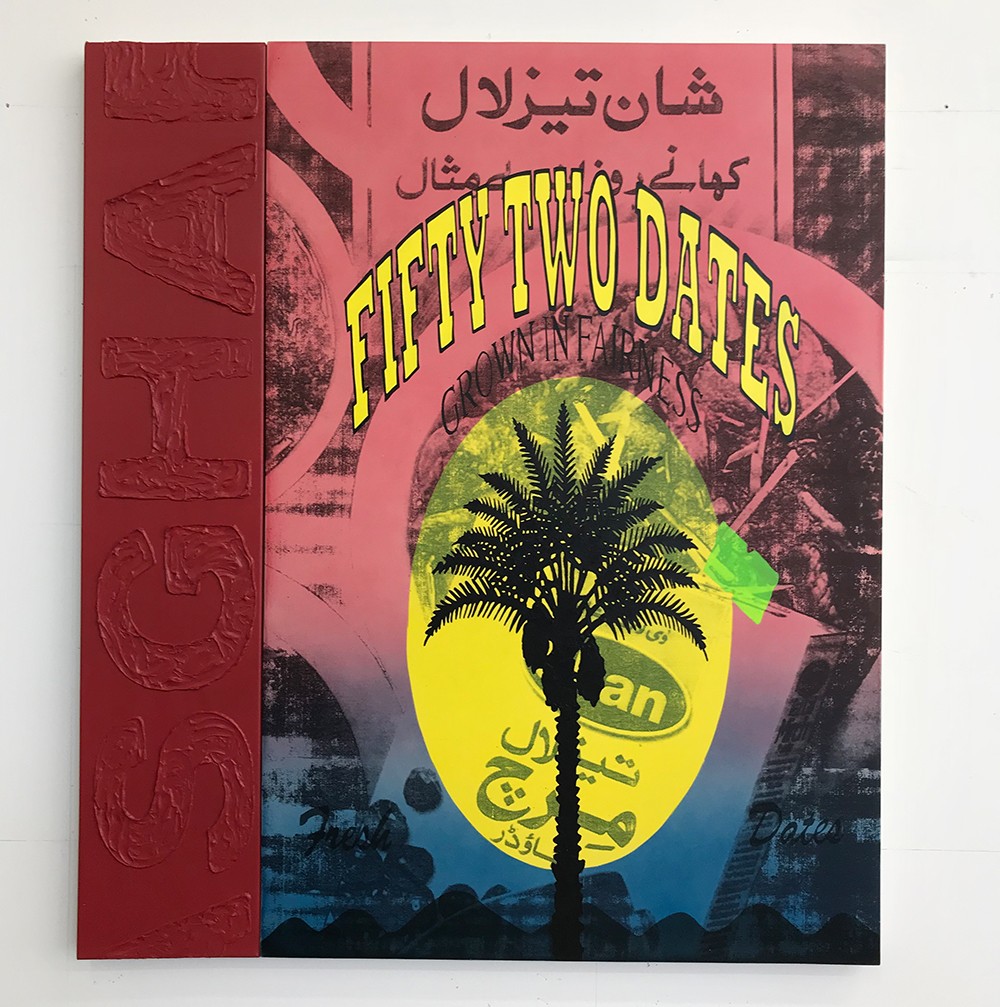

Asghar, a daughter of Pakistani immigrants, explains how being part of both Pakistani and American culture has made her feel suspended in the middle of both at times. “I’m Pakistani but when I go there I don’t feel like I can relate in the same way,” she explains. “But when I’m here, obviously I have a different experience than a lot of people.” The marrying of these identities resulted in a duality that manifests itself in Well Wishes. Inspired by cartoon imagery of her youth from The Lion King and Aladdin, as well as the vibrant colors from old Indian music videos, Asghar brings worlds together to create one that is uniquely her own.

She explains that the journey to arrive at her true self was traveled on a path of resistance. “I was so afraid of being connected to the aesthetic that is being brown,” says Asghar. “And I was always chasing something else to make sure that I didn’t look like that.” This reluctance to be put into a pre-existing schema of what “Pakistani art” should look like caused Asghar to create her own category and encourage others to do the same. “Art coming from a brown woman doesn’t have to look a certain way,” she stresses.

Using a combination of painting, screenprinting, and found objects from her familial archive, Asghar projects her inner monologue and spirit onto the canvas in Well Wishes. The pieces range from dreamy landscape to re-thought adverts from Pakistanian digest magazines and old cassette inserts. The fluctuation between the literal and the ethereal serves as a map to Asghar’s mind, a representation of the conscious and the subconscious. It causes the viewer to explore which aspects of their environment directly influence them and which ones crawl under the cracks of their subconscious, guiding their actions in ways they don’t realize until later in life, if ever.

Asghar explains experiencing this phenomenon while reflecting on how music has influenced her work. As some of the first from their family to move to America in ’79 and ’80, Asghar’s parents provided a welcome hub for visitors and family members on their way to the states. Asghar says that, more often than not, her house full of family would burst into song, whether it was her uncle using the table as a drum and everyone singing along or listening to one of the many cassettes that were sent back and forth between family members. “I adore old Indian music from the 1940s onward. It’s constantly in the studio and I sing the songs to my daughter before bedtime,” she says. “I like to think about the paintings being a variation of that music… like if I was able to remix, how would I remix those songs?”

She explains that many of the colors used in her landscape works are hues she would see in the Indian music videos that served as the soundtrack of her life. These colors are blended to make contemplative scenes that are easy to escape into. While Asghar thinks of all paintings as portals, the idea was especially pertinent when she started to experience motherhood. “I just started thinking of the female body as a portal to bring life into the world,” says Asghar, “So, I started to make portals within the portals of paintings.”

The paintings serve as a physical representation of Asghar’s psyche — her joy, anger, hope, wonderment. Places she escapes to or ruminates in. In creating these portals, Asghar realized that these surreal landscapes represented her even identity better than the physical totems she was using in her work to begin with. “Identity is a place that doesn’t exist,” she muses. “They are just these made up spaces and places and that is actually a better representation of our layered selves.”