Amna Asghar’s gently captivating new paintings, on display at Klaus von Nichtssagend Gallery on the Lower East Side, explore a rich variety of experiences and perceptions associated with the geographical movement or cultural displacement. Such a shift could be a matter of orderly emigration, traumatic upheaval, or impulsive wanderlust. Whatever its nature, Asghar unabashedly explores much of it from a chair in front of a computer. Such is now life. While each piece stands nicely on its own as a visual hook, the paintings are best taken in collectively, to gain the full, rich context of her work.

The twelve pieces in the show range from sky paintings of uncomplicated beauty to intensely narrative canvases calling for study, triangulation, even research. In the first category are two dreamy acrylic paintings, Hamtramck and New York, based on photographs. The one is brooding pink and purple, the other slashing blue and white. A Pakistani-American born and based in Detroit, Asghar may be contrasting the downbeat sense of repose she feels there with the potential for kinetic renewal in New York. That’s just a guess, but one prompted by their co-installation. A third sky painting, Agra and Baghdad, is more abstract and presumably more remote from her actual experience, though its deep blue serenity carries some immediate irony.

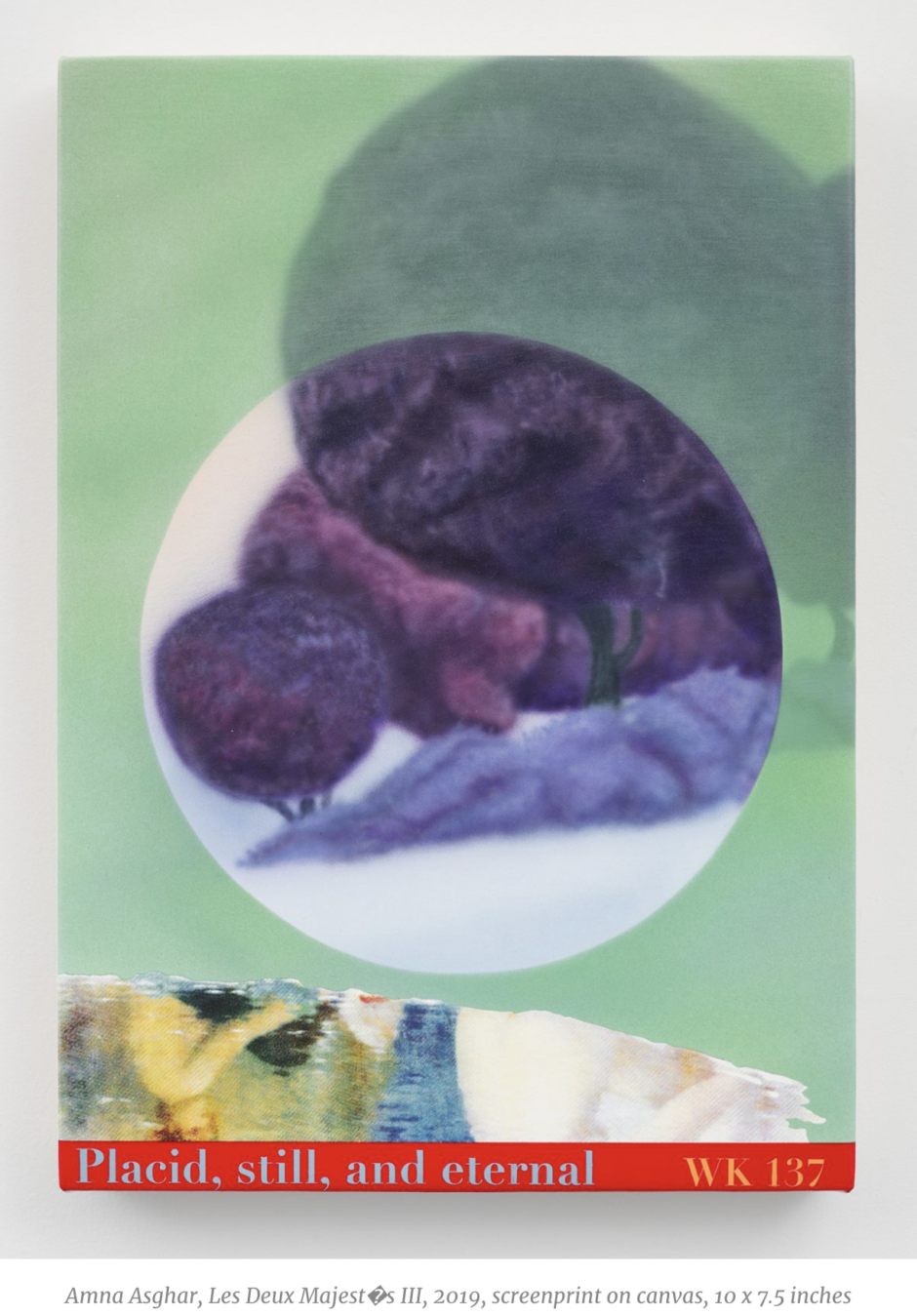

Five small screenprints capture the sunset in Jean-Léon Gérôme’s orientalist painting Les Deux Majestés (The Two Majesties) of a lion looking across the desert – a Kipling-esque scene if ever there was one. (His painting The Snake Charmer infamously adorned the cover of Edward Said’s groundbreaking polemic Orientalism.) They are pleasing, but potentially tainted, as many would say that the appropriated imagery originally depicted Africa with the romanticized condescension that Said deplored. Interspersed among the other pieces, they might impart the idea that interpretations, however flawed, are part of history and sometimes, broken down and recapitulated, can yield unobjectionable components of lasting value. The exhibition itself makes the case with considerable sophistication, and without denigrating the notion of truth.

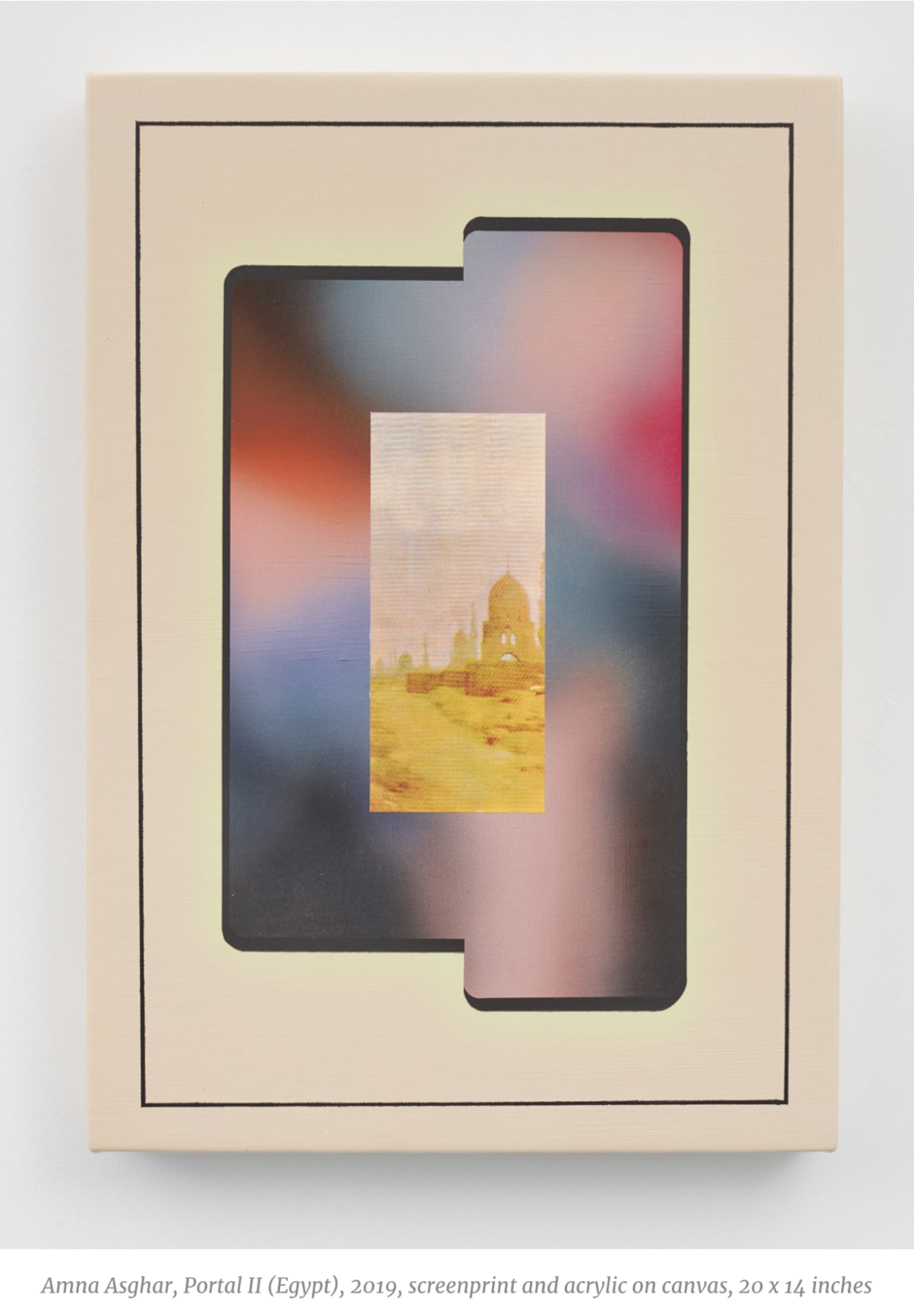

They Met Me at the Gate, Portal II (Egypt), and Portal I (Wk. 137) may best vivify Asghar’s apprehension of paintings as portals; that is, entryways to something bigger and different. Variegated and layered, and combining screenprint and acrylic, each of these pictures tells or at least alludes to a specific story. The first two involve refugees departing their respective countries; their incongruously bright, cheerful coloration obliquely implies their hardship, more directly others’ obliviousness to it. The third cadges a fragment of another pastoral scene of Gérôme’s, this one of women bathing in a reflecting pool, beneath a scoped, essentially abstract painted image, possibly of trees, suggesting nature benighted. Captioning the piece is Said’s description of how the West portrayed the Orient: PLACID, STILL, AND ETERNAL. The sentiment is time-stamped Wk. 137: Trump’s 137th week in office. Said’s Other, it seems, may soon see fit to turn the tables and caricature the West. For all the nuance in her understanding of its foibles, Asghar also knows unmitigated ugliness when she sees it.