At first, the ten small oil paintings on jute in Jennifer J. Lee’s exhibition “Day Trip” seemed entirely random in subject matter. What, for instance, does a mandala of spiraling pink turkey wings have to do with scenes of ocean waves? But the various juxtapositions created a stoned kind of logic. The poultry parts began to resemble legs on a beach, perhaps, their skin dimpled by a sudden chill. Nearby, a painting showing angled stacks of plastic chairs—Stacked Chairs (2018)—brought this narrative into backyard barbeque territory.

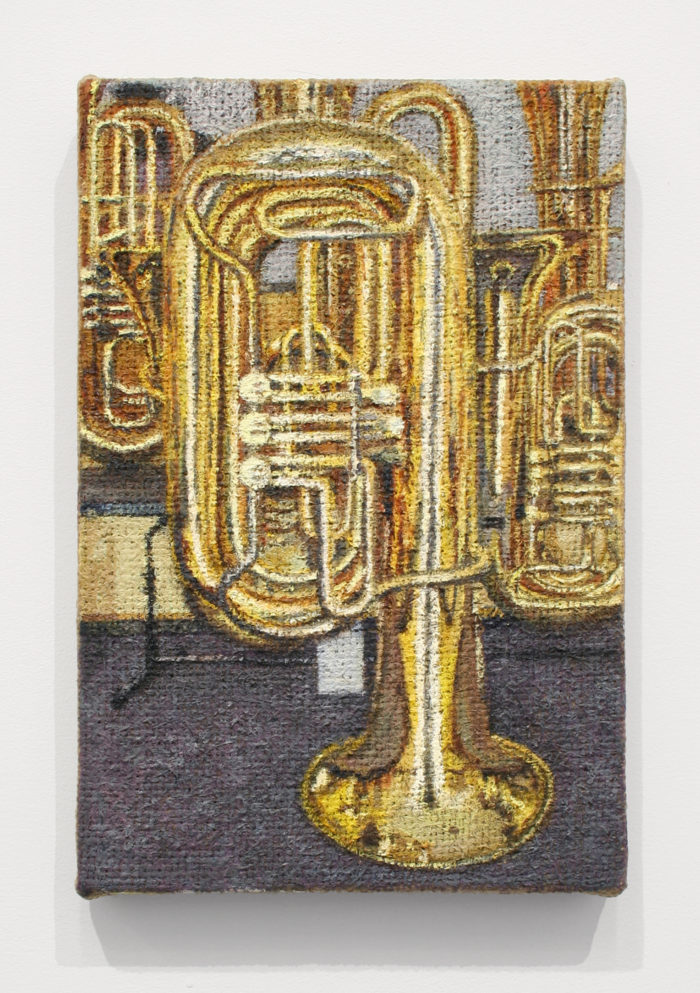

The trippy vibe continued with Tubas (2018), where a grouping of the title instruments hypnotizes with its gleaming surfaces, and with Dandelions (2017), an especially exciting work hung in a hallway. The colors in this latter painting stand in vivid contrast to the muted palette of the other scenes—the effect is intoxicating. Two dandelions bleed red and blue from their sides, as if you’re hallucinating, or as if this were an image meant to be viewed with 3D glasses or were a badly aligned offset print. More colorful flora is found in Standing Flowers (2018), in which an arrangement of purplish buds and scattered sunflowers is set against a neutral-colored corner of a room to striking effect. Adorned with a satiny violet rosette, the arrangement suggests acknowledgment of some kind of event—congratulations on getting married, condolences on the death of your loved one, welcome to this corporate summit. It is remarkably occasion-neutral and, like the rest of the show, encourages you to project your own web of associations.

What even is this place we’re day tripping to or tripping in? There’s a sense that Lee is painting results from Google image searches, just as a landscape painter might paint a lake vista. The prosaic, matter-of-fact titles of the works read like search-engine-optimized keywords, while the rough, gridded weave of the jute creates a certain low-resolution pixelation. Hito Steyerl’s concept of “poor images” might come to mind, but these paintings don’t feel like bad-quality copies or lossy JPEGs so much as dynamic transformations.

Lee excels at interiors and images of the man-made. Infinity Mirror (2018) shows the recursive effect suggested by the title playing out in a public restroom. The glass grows greener with every reflection, but instead of the precise rectangular mise en abyme you might expect, the image rotates and loosens a bit in each iteration to evoke a ripple in time and space. Also stunning are two larger paintings of glass bricks, Window II and Window III (both 2018), through which other scenes are blurrily glimpsed, tantalizingly out of view. Lee’s landscapes, whether the aforementioned wave works or a nice-enough portrayal of a garden, suffer in comparison. These vistas of nature are noticeably less tight, suggesting scenes zoomed in on by a camera. Their haphazard quality invokes the way you might take a trip to the beach only to drink beer with your back to the ocean.